Matthew Paris, Flores historiarum (London: Thomas Marsh, 1570).

Matthew Paris, Flores historiarum (London: Thomas Marsh, 1570).

[12], 440, 466, [22] pp., 30cm.

London, Royal College of Physicians Library, 10653 D1/19-e-7.

Few medieval English historians could be more recognized or more acclaimed than Matthew Paris (1200-1259). His engaging and sometimes biting accounts of his own times, gleaned from personal acquaintance with the figures concerned as well as from documentary evidence, won him praise from his medieval peers and from modern historians alike. Paris’s contemporary accounts in the Flores (as in the Chronica maiora) adapted the earlier material from a synonymous history written by Matthew’s predecessor, Roger of Wendover, which attempted to chronologically reconcile the reigns of England’s kings with the dates of universal history. This work would provide both material for later historians to reproduce and a critical model for them to emulate, and would secure Paris’s reputation as the wellspring of a tradition of institutional history at St. Albans that would endure for nearly two centuries after his death. As gifted an artist as a writer, Paris illustrated the manuscripts he copied and also composed one of the most detailed medieval maps of Britain.

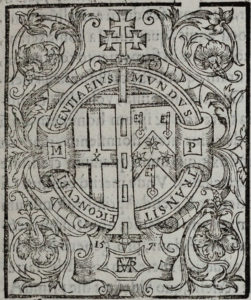

This edition, as well as the histories of Thomas Walsingham in Dee’s library, were products of a period of intense investigation into English antiquity centered around the person and library of Matthew Parker, Elizabeth’s archbishop of Canterbury. Both Parker and Elizabeth’s treasurer, William Cecil, had encouraged the study of England’s ancient past, in defense both of the legitimacy of its church and its territory. Parker took pains to acquire as many copies of Matthew Paris’s works as he could (including two illustrated copies of the Chronica maiora), perhaps envisioning himself in the tradition of the St. Albans historians. While his name does not appear anywhere in the work, at the opening of the preface to the Flores, the first initial contains his arms and motto (mundus transit et concupiscentia eius), along with the initials M.P.

See B. S. Robinson, “‘Darke Speeche’: Matthew Parker and the Reforming of History,” Sixteenth-Century Journal 29:4 (1998), 1061-83.

― Neil Weijer