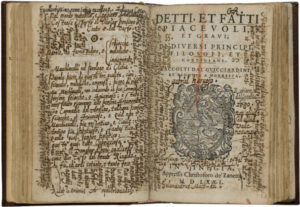

Lodovico Guicciardini (1521-89), Detti, et fatti piacevoli et gravi, di diversi principi filosofi, et cortigiani (Venice: Christoforo de’ Zanetti, 1571) [BOUND WITH: Lodovico Domenichi, Facetie, motti, et burle (1571)]. 211 leaves ; 16 x 11 cm. Folger Shakespeare Library, H.a.2.

Lodovico Guicciardini (1521-89), Detti, et fatti piacevoli et gravi, di diversi principi filosofi, et cortigiani (Venice: Christoforo de’ Zanetti, 1571) [BOUND WITH: Lodovico Domenichi, Facetie, motti, et burle (1571)]. 211 leaves ; 16 x 11 cm. Folger Shakespeare Library, H.a.2.

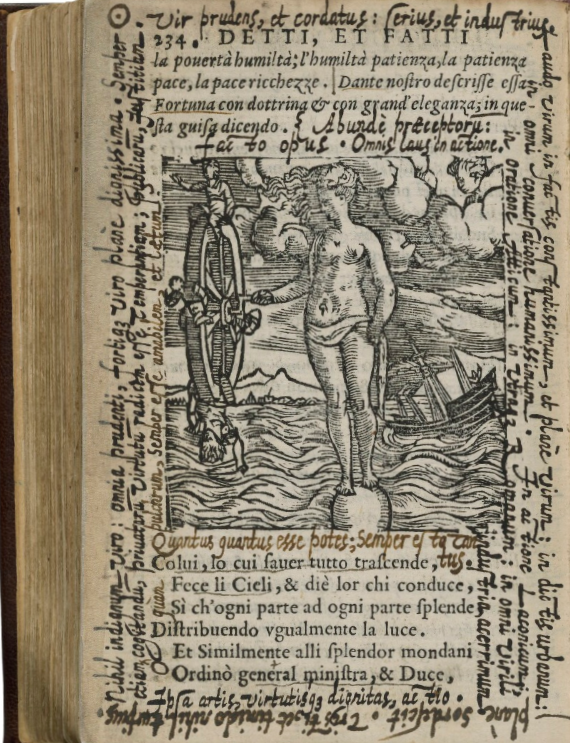

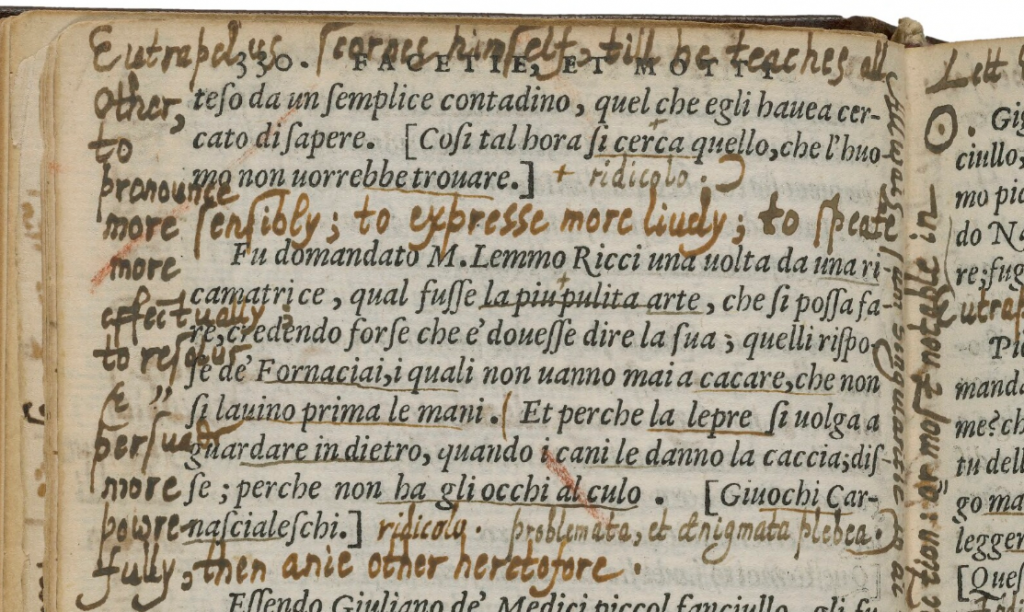

It is perhaps ironic that Harvey wrote on the title page of one of the two books bound together in this volume, both of them dedicated to the bon mot, “There is hardly any end to discourses [Discursuum vix ullus finis]” (fol. 73r). The 360-degree, wrap-around manuscript annotations that fill nearly every centimeter of white space in this narrowly margined book—consisting of a complete copy of Guicciardini’s Detti e fatti (1571), and a partial fragment of its companion imprint, Domenichi’s Facietie (1571)—positively burst at the seams, sometimes inspiring vertigo (especially when you rotate the images at 90-degree angles in the Archaeology of Reading viewer). Big things do sometimes come in small packages, however, and Harvey’s little octavo Domenichi/Guicciardini volume presents one of the most challenging, and revealing discursive spaces in all of Harvey’s great enterprise of annotation. Taken together, it is in this composite volume that Harvey shows most clearly to the latter-day reader the single, most utterly idiosyncratic aspect of his reading practice: the deployment of a personal dramatis personae, each character of which periodically struts across the stage of a book, much like a player delivering lines from Harvey’s own mental script, and embodying either an aspect of his own psyche, or one of his obsessional categories of self-cultivation. By far the most common of these (in this volume, and in the Archaeology of Reading corpus more generally) is Eutrapelus, a figure whose every facet seems to express Harvey’s powerful ambition to master modern languages, particularly in the service of wit, puns, and jests that “draw salt from the earth and light from the world” (fol. 82v; a gesture to the gospel, Matthew 5:13-16 that reverberates throughout the volume: see also fols. 47v, 185r).

As Harvey tells it in an especially unguarded moment of clear self-exposition, Eutrapelus is a picture of the courtly extrovert, a memorable orator and the natural life of any party (which Harvey, by all accounts, was not). The persona derived from the classical Roman eques Publius Volumnius Eutrapelus, a witty Roman and friend of Mark Antony mentioned repeatedly by Cicero): “Eutrapelus scornes himself, till he teaches all other, to pronounce more sensibly; to expresse more liuely; to speake more effectually; to resolue & persuade more powrefully, then anie other heretofore” (image at right). He continues further along in the Guicciardini: “Each is most prudent and most splendid. Others assert serious matters, but only Eutrapelus carries out serious matters. He accomplishes exceptional things. Eutrapelus changes great into small, and small into great.” This is the “mysterious transformation [arcana metamorphosis] of Eutrapelus,” Harvey continues, where the “serious matters of others must be converted into playthings. Your playthings must be converted into serious matters.” Seeming to enjoin himself to a lasting memory of the point, Harvey completes this strain of self-obligation in the second person singular: “One associates with strangers hyperbolically or ironically, but withhold this tendency with your friends. Apart from your own matters, all is for naught” (82v). Harvey has been so warned by his dear friend, Eutrapelus, who whispers in his ear from the margins of his books.

These imprinted texts, which seem to captivate Harvey and seduce his Eutrapelus, are basically playful and unserious – at turns flip and piquant and hardly canonical. The Italian merchant of Antwerp, Lodovico Guicciardini, is far better remembered for his Descrittione di…tutti i Paesi Bassi (1567), dedicated in the Italian and subsequent French editions to the monarchs of Spain and uniquely descriptive of the most noteworthy Netherlandish painters of that time, reflecting Philip II’s passion for their art. The eponymous Lodovico Domenichi, a humanist translator and editor of classical works, is similarly remembered for other books: his Polybius, Plutarch, and Pliny the Elder, and more recently for editing in 1559 one of the earliest collected editions of women poets (as well as a couple of frauds: the false “Letter of Aristeas” and a fake, neo-Latin Senecan play). Their relatively light texts, as is suggested by their respective, informal titles, appear almost as well-coiled springboards for Harvey’s fertile imagination and love of wordplay. They are not so much “wisdom literature” as echo-chambers in which he can overhear himself saying wise and clever things in polite conversation and in company (Harvey signed and dated the Guicciardini “1580,” suggesting that he may have annotated the volume while still eyeing a position at court). These light literary passages invoke the sense of a theater for the performance, ostensibly ex tempore, of Harvey’s extensive reading and ready command of the best works on a given or curious topic, sometimes digressing even into mini-bibliographies such as his memorable litany of thaumaturgy, which is barely connected to the presumed “anchor text” of the printed page on which it appears:

After the Introduction on Magic in Albertus Magnus’s De Mirabilibus Mundi, Roger Bacon’s De mirabili potestate artis et naturae, Pomponazzi’s De incantationibus, with Agrippa’s aptly titled De occulta philosophia and De inceritudine et vanitate scientarium. No collection of Thaumaturgy is more propitious than the De vita Apollonii Tyanei: with Gandini’s Stratagemata and the Polytechnics, Politics, and Economics of Aristotle. With Giovanni Battista Porta’s Phytognomonica, Albertus on physiognomy, and the De Secretis of Cardano and Wecker (387).

See “Guicciardini, Lodovico.” Grove Art Online. Oxford Art Online (Oxford University Press, online edn., Sept. 2016) http://www.oxfordartonline.com/subscriber/article/grove/art/T035507; Deanna Shemek, “The Collector’s Cabinet: Lodovico Domenichi’s Gallery of Women,” in Pamela Benson and Victoria Kirkham (eds.), Strong Voices, Weak History: Early Women Writers and Canons in England, France, and Italy (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2005), 239-62. AOR Bookwheel Blog Entries: Chris Geekie, “Harvey’s Joke Books;” “On Readers and Repetition.”

― Earle Havens