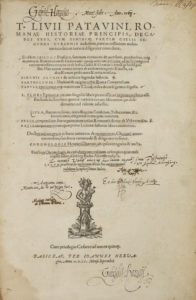

Titus Livius Patavini [Livy] (d. 17? CE), T. Liuii Patauini Romanae historiae principis decades tres [Ab urbe condita] (Basel: Ioannes Heruagios, 1555). [16], 829, [288] p.; 39 cm. (fol.). Princeton University Library, Department of Rare Books and Special Collections, South East (RB) (Ex) PA6452 .A2 1555q.

Titus Livius Patavini [Livy] (d. 17? CE), T. Liuii Patauini Romanae historiae principis decades tres [Ab urbe condita] (Basel: Ioannes Heruagios, 1555). [16], 829, [288] p.; 39 cm. (fol.). Princeton University Library, Department of Rare Books and Special Collections, South East (RB) (Ex) PA6452 .A2 1555q.

Harvey’s Livy is rightly famous, not only for the exhaustive Elizabethan rereading of it, but also for the Jardine/Grafton re-reading (i.e., “How Gabriel Harvey Read His Livy”), which is, in turn, essential reading for any student of the Archaeology of Reading project (thus, no attempt at a rendition here). The imprint itself was produced by Johann Hervagius, the immediate successor of Erasmus’s favorite Basel printer Johann Froben, whose printer’s mark on the title page of Harvey’s Livy is the thrice-headed Hermes Trismegistus bearing, in deference to his former master, Froben’s justly famous device of the caduceus. This attribute of Mercury as both messenger god and the god of commerce lent inspiration to the formulation of Erasmus’s slightly arch commendation of the younger printer and his new “rebranding” strategy: “if your three-headed Hermes is propitious…I hope that god will show you a short and easy way to Plutopolis. That is the place to which most people in these days are running as fast as they can, but not all with like success.” In the same letter of August 1531, Erasmus singled out the late Froben for his singular dedication to the “noble enterprise” of printing: “Nothing bound me to him more closely than his life-long determination, at any cost of money and of labor, to promote general learning by the publication of the most approved authors.”

Harvey’s luxuriously printed copy of Livy is just such a book, sparing little “cost of money and of labor,” and it is perhaps a further coincidence that Erasmus’s letter was addressed to Hervagius from Freiburg im Breisgau, for that is also where the Swiss scholar, Henricus Glareanus, famously lectured on Roman history and produced an influential chronological table of ancient history that was frequently reprinted with Livy’s text, as in the case of Harvey’s copy. In yet another parallel, though one surely unknown to Harvey, Glareanus himself took to the habit of not only carefully annotating his own copy of the chronology in manuscript, but also allowing his students on numerous occasions to copy out these marginalia into their own printed copies of the tables.

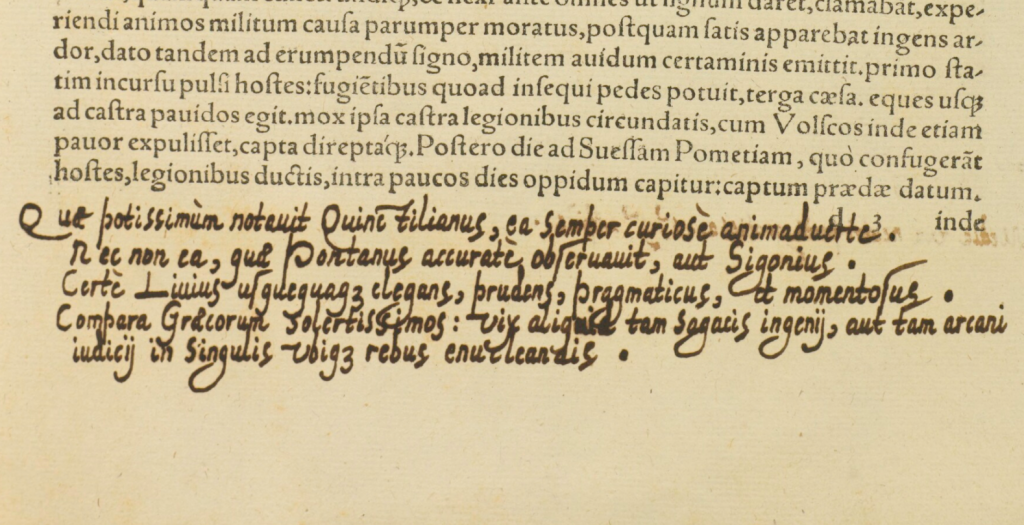

While Harvey himself did not annotate his Glareanus chronology as heavily as he did Livy’s text, it is certain that Glareanus’ presence nonetheless inspired him to write out a separate apparatus of his own: a chronological “catalogue of famous men in Roman history, copied in sequence,” which fills the ample and convenient white space afforded by a much-indented table of imperial weights and measures in the front matter of the Hervagius edition (fol. 4r) and also reminds the latter-day reader that not all of Harvey’s manuscript annotations are necessarily anchored to the printed words they surround. This is clear because Harvey says as much in his marginalia, on multiple occasions praising Glareanus’s precise glosses and rigorous readings of Livy and, in this way, parroting his own sky-high self-expectation as one of the most rigorous readers in history: “The Livian expositions of Glareanus and Velcurio should be skimmed one by one, at least after reading each one of the individual books, in case one accidentally missed out on something worthy of particular notice. For some things here are rich in meaning and precise; and most are of at least some significance.” He continues, “No commentator before Velcurio was more learned than Glareanus, nor was there any more accurate chronologer and geographer before Funcius and Mercator” (fols. 431r, 432v).

While Harvey himself did not annotate his Glareanus chronology as heavily as he did Livy’s text, it is certain that Glareanus’ presence nonetheless inspired him to write out a separate apparatus of his own: a chronological “catalogue of famous men in Roman history, copied in sequence,” which fills the ample and convenient white space afforded by a much-indented table of imperial weights and measures in the front matter of the Hervagius edition (fol. 4r) and also reminds the latter-day reader that not all of Harvey’s manuscript annotations are necessarily anchored to the printed words they surround. This is clear because Harvey says as much in his marginalia, on multiple occasions praising Glareanus’s precise glosses and rigorous readings of Livy and, in this way, parroting his own sky-high self-expectation as one of the most rigorous readers in history: “The Livian expositions of Glareanus and Velcurio should be skimmed one by one, at least after reading each one of the individual books, in case one accidentally missed out on something worthy of particular notice. For some things here are rich in meaning and precise; and most are of at least some significance.” He continues, “No commentator before Velcurio was more learned than Glareanus, nor was there any more accurate chronologer and geographer before Funcius and Mercator” (fols. 431r, 432v).

Despite this high praise, the Swiss scholar proved less important to Harvey on what was, arguably, his single most important engagement with any text in his library: his personal service as a “professional reader” to Philip Sidney on the eve of Sidney’s much-anticipated embassy to the court of the newly anointed Holy Roman Emperor in Prague:

The courtier Philip Sidney and I had privately discussed these three books of Livy, scrutinizing them so far as we could from all points of view, applying a political analysis, just before his embassy to the emperor Rudolf II. He went to offer him congratulations in the queen’s name just after he had been made emperor. Our consideration was chiefly directed at the forms of states, the conditions of persons, and the qualities of actions. We paid little attention to the annotations of Glareanus and others.

For Harvey, reading Livy’s Ab Urbe Condita, the greatest of the ancient histories of Rome, which traces its rise from mythical origins to the reigns of Julius and Augustus Caesar, also achieved the very purpose of history itself: to remember forever the accomplishments of great men (Harvey’s called his front-matter index his “golden list of the most famous Romans” [celeberrimorum Romanorum aureus catalogus]).

The ultimate achievement of books of history, and of his own marginalia recorded within them, was to catalogue and “imprint” the bravery of these men of action indelibly, even “strikingly,” in an “art of remembering”—language that is unmistakably redolent of the physical action of a printing press. “Bravery” also appears as one of the single most frequently used words in all of Harvey’s marginalia, both in the works of Livy and across the entire Archaeology of Reading Harvey corpus: “These, then, are the most select of already famous men, from the superior history of the Roman Republic, in particular the bravest [praesertim suorum omnium fortissimo] and wisest of them all. Hardly any other memory list deserves a deeper imprint, so great is the importance of those brilliant names. In them is strikingly represented the art of remembering all Roman history” (fol. 4r). See Lisa Jardine and Anthony Grafton, “‘Studied for Action’: How Gabriel Harvey Read His Livy,” Past and Present 129:1 (1990): 30-78; Jardine, “‘Studied for Action’ Revisited,’” in Ann Blair and Anja-Silvia Goeing (eds), For the Sake of Learning: Essays in Honor of Anthony Grafton, 2 vols. (Boston: Brill, 2016), 2:997-1017; Anthony Grafton and Urs Leu (eds.), Henricus Glareanus’s (1488-1563) Chronologia of the Ancient World: A Facsimile Edition of a Heavily Annotated Copy Held in Princeton University Library (Boston: Brill, 2014). The original letter from Erasmus to Hervagios is printed in the front matter of Erasmus’s Epistularum floridarum liber unus (Basel: Hervagios, 1531), 3. Jaap Geraerts, AOR Bookwheel Blog Entry, “Pro Se Quisque.”

― Earle Havens