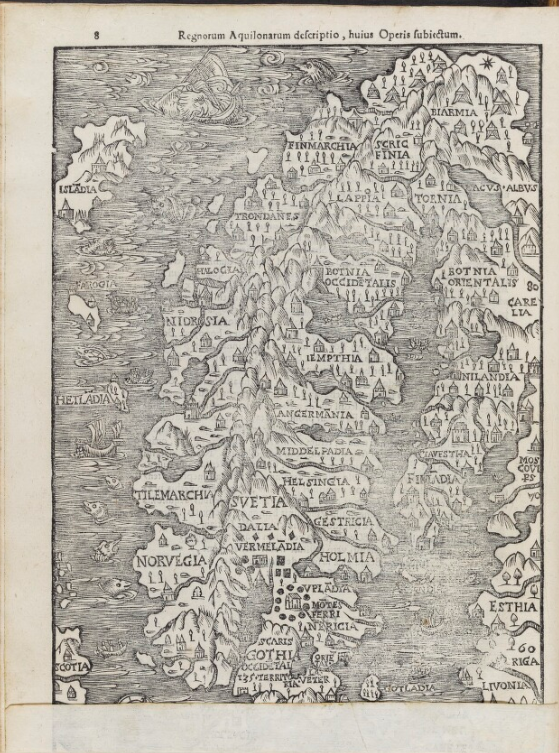

Olaus, Magnus, Archbishop of Uppsala (1490-1557/58). Historia de gentibus septentrionalibus, earumque diuersis statibus, conditionibus … ac mineris metallicis, & rebus mirabilibus, necnon vniuersis penè animalibus in septentrione degentibus, eorumq[ue] natura: Opus vt varium, plurimarumque rerum cognitione refertum, atque cum exemplis externis, tum expressis rerum internarum picturis illustratum, ita delectatione iucunditat’eque plenum, maxima lectoris animum voluptate facilè perfundens (Rome: Ioannem Mariam de Viottis, 1555). [84], 815, [1] p.: ill., map; 27 cm. fol. Princeton University Library, Department of Rare Books and Special Collections, South East (RB) (Ex) DL45.O438 1555q.

Olaus, Magnus, Archbishop of Uppsala (1490-1557/58). Historia de gentibus septentrionalibus, earumque diuersis statibus, conditionibus … ac mineris metallicis, & rebus mirabilibus, necnon vniuersis penè animalibus in septentrione degentibus, eorumq[ue] natura: Opus vt varium, plurimarumque rerum cognitione refertum, atque cum exemplis externis, tum expressis rerum internarum picturis illustratum, ita delectatione iucunditat’eque plenum, maxima lectoris animum voluptate facilè perfundens (Rome: Ioannem Mariam de Viottis, 1555). [84], 815, [1] p.: ill., map; 27 cm. fol. Princeton University Library, Department of Rare Books and Special Collections, South East (RB) (Ex) DL45.O438 1555q.

This Swedish historian and geographer was brother to the Archbishop of Uppsala and, upon his brother’s death was appointed by Pius III to succeed him as archbishop-in-exile in Rome in the face of the Lutheran Reformation in Scandinavia. Olaus spent the rest of his life in Italy, serving as a representative at the Council of Trent in its first years and publishing biographies of the mother and daughter saints of Sweden, Saints Bridget and Catherine of Vadstena, among others. He is best known, however, for his encyclopedic knowledge of Nordic geography, natural history, trade, politics, ethnography, and folklore, particularly of his native Scandinavia and the Baltic. Despite its girth and great expense, Olaus’s massive twenty-two book history of the northern peoples of Europe was a bestseller throughout the middle decades of the sixteenth century, emerging in Latin, German, and Italian from the printing centers of Rome, Venice, Basel, Strasburg, Antwerp, and (nearly a century later) in further translations into English and Dutch.

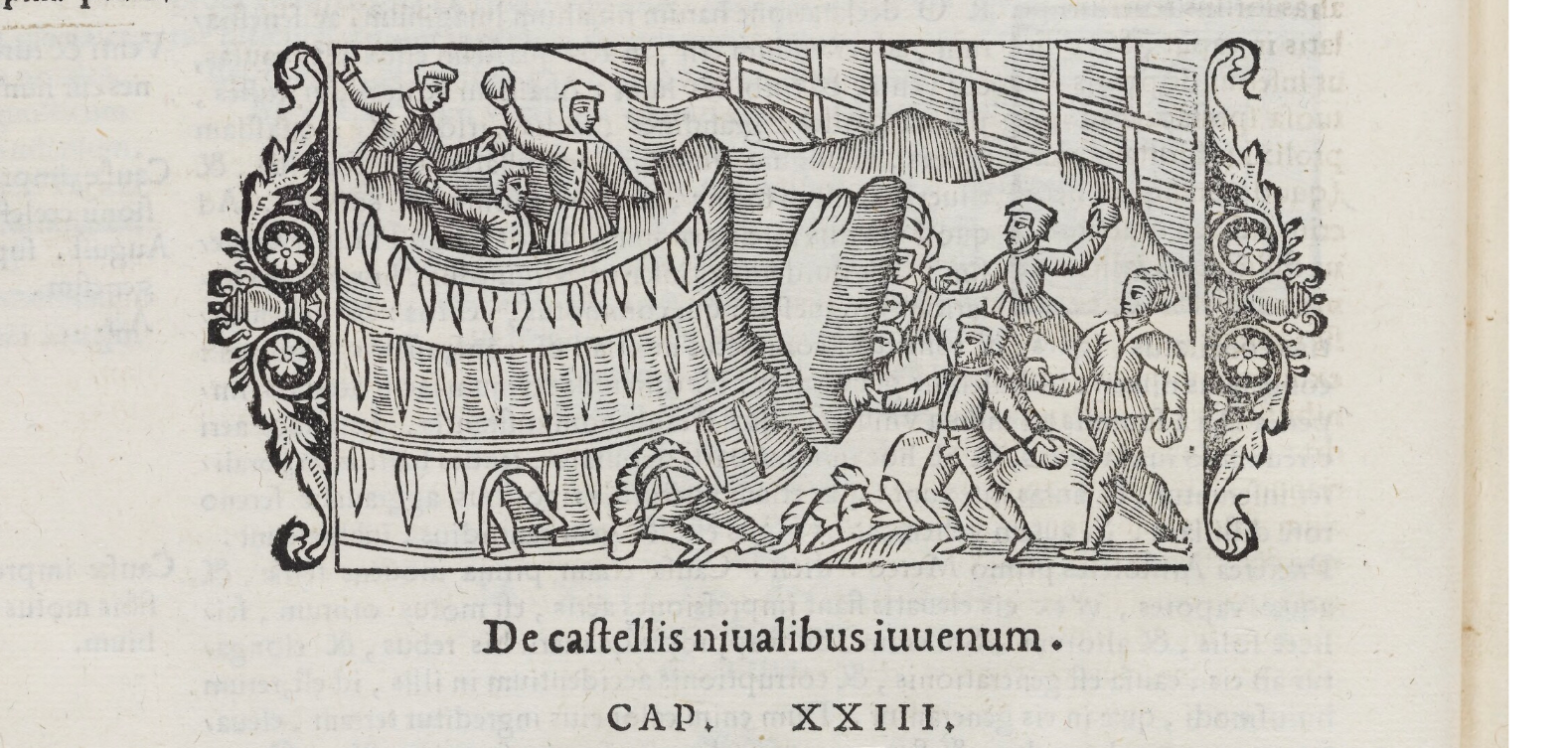

Harvey’s annotated copy happens to be the editio princeps of this work, illustrated throughout with original, sumptuously executed woodcut engravings. He was also effusive with praise for its textual and visual contents, marking it as “useful as it is replete with the inquiry of the greatest and largest variety of things; it is illustrated not only with external examples, but also with distinct pictures of domestic matters; thus it is full of delightful, pleasant, and incredible things, easily imbuing the mind of the reader with enjoyment.” Curiously, Harvey also noted in his marginalia that the imprint was specifically “secured by the privilege of Pope Julius III.” Another extensive annotation on the final page of the volume responds to the printed contents in a far more immediate context, exploring the mythical origins of and practical remedies for the gout—a condition from which even the highest in the land suffered from at the time. A man ever mindful of his times, and aware of the gouty condition of several of the most prominent men in the land, he speculates: “Can it be that Nicholas Bacon, Keeper of the Great Seal, and William Cecil, the English treasurer, are without this remedy? Two most prudent and delightful men” (fol. 286v). See Olaus Magnus, Historia de gentibus septentrionalibus: Romæ 1555 [Description of the northern peoples: Rome 1555], ed. Peter Foote; Trans. Peter Fisher and Humphrey Higgens; 2nd srs., vols. 182, 187-88 (3 vols.; London: Hakluyt Society, 1996-98). AOR Bookwheel Blog Entries, Amanda Brunton, “A Look at the Lightly Annotated Books;” Chris Geekie, “Swedes, Lawyers, and Pi.”

Harvey’s annotated copy happens to be the editio princeps of this work, illustrated throughout with original, sumptuously executed woodcut engravings. He was also effusive with praise for its textual and visual contents, marking it as “useful as it is replete with the inquiry of the greatest and largest variety of things; it is illustrated not only with external examples, but also with distinct pictures of domestic matters; thus it is full of delightful, pleasant, and incredible things, easily imbuing the mind of the reader with enjoyment.” Curiously, Harvey also noted in his marginalia that the imprint was specifically “secured by the privilege of Pope Julius III.” Another extensive annotation on the final page of the volume responds to the printed contents in a far more immediate context, exploring the mythical origins of and practical remedies for the gout—a condition from which even the highest in the land suffered from at the time. A man ever mindful of his times, and aware of the gouty condition of several of the most prominent men in the land, he speculates: “Can it be that Nicholas Bacon, Keeper of the Great Seal, and William Cecil, the English treasurer, are without this remedy? Two most prudent and delightful men” (fol. 286v). See Olaus Magnus, Historia de gentibus septentrionalibus: Romæ 1555 [Description of the northern peoples: Rome 1555], ed. Peter Foote; Trans. Peter Fisher and Humphrey Higgens; 2nd srs., vols. 182, 187-88 (3 vols.; London: Hakluyt Society, 1996-98). AOR Bookwheel Blog Entries, Amanda Brunton, “A Look at the Lightly Annotated Books;” Chris Geekie, “Swedes, Lawyers, and Pi.”

― Earle Havens