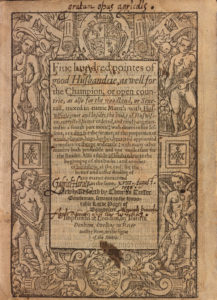

Thomas Tusser (1524?- 80), Fiue hundred pointes of good husbandrie: as well for the champion, or open countrie, as also for the woodland, or seuerall, mixed in eurie month with huswiferie, ouer and besides the booke of huswiferie, corrected, better ordered, and newly augmented to a fourth part more, with diuers other lessons, as a diet for the fermer … also a table of husbandrie … and another of huswiferie … for the better and easier finding of any matter conteined in the same (London: Henry Denham, 1580). [1], 89, [1] leaves; 19 cm (4to). STC (2nd ed.), 24380. Princeton University Library, Department of Rare Books and Special Collections, RHT 16th-99a.

Thomas Tusser (1524?- 80), Fiue hundred pointes of good husbandrie: as well for the champion, or open countrie, as also for the woodland, or seuerall, mixed in eurie month with huswiferie, ouer and besides the booke of huswiferie, corrected, better ordered, and newly augmented to a fourth part more, with diuers other lessons, as a diet for the fermer … also a table of husbandrie … and another of huswiferie … for the better and easier finding of any matter conteined in the same (London: Henry Denham, 1580). [1], 89, [1] leaves; 19 cm (4to). STC (2nd ed.), 24380. Princeton University Library, Department of Rare Books and Special Collections, RHT 16th-99a.

The former court musician Thomas Tusser’s agricultural harvests were, perhaps ironically, far more successful in print than in the good earth. His treatise on farming went through over twenty editions from its first appearance in 1557, most of them Elizabethan (thus making it an all-time bestseller in the already storied history of Elizabethan verse), up through the initial decades of the 17th century. Its several iterations and expansions, reflected in the densely and variously worded title of Harvey’s particular edition, basically follow the rhythms of the seasons in serviceable and memorable georgic verse. The text offers up practical knowledge and advice of “husbandrie,” coupled with the domestic arts of household “huswifery,” providing invaluable insights into early modern country life set within the context of a modest farmstead (thus Harvey’s condescending characterization in the book’s end matter of Tusser as a pastoral poet fitted “for common life, and vulgar discourse”).

The handsome black letter of this imprint belonged to the embattled stationer Henry Denham, whose name appears often in the livery records of the Court of the Stationers for many, many infractions and fines—the telltale sign of a true entrepreneur ready to push the boundaries of what was permissible in this highly regulated commercial trade. The Worshipful Company of Stationers eventually made a virtue of Denham’s energy and intrigue, appointing him an official “searcher” and “renter warden” around the time he printed his 1580 Tusser, and “under-warden” of the Company years later (though he was fined again for using indecent speech to an upper warden in 1584). There is one other fairly random association worth mentioning, which is nonetheless particularly revelatory of the litigious and unscrupulous nature of the Elizabethan printing trade. Despite formally petitioning against crown grants of special printing privileges, Denham seems perfectly happy to have been assigned William Seres’s royal privilege of printing psalters and other liturgical books, and to take possession of all Seres’s “presses, letters, stock, and copies” of books for an annual rent. This furniture from Seres’s shop would very likely have included the original press on which Seres had printed Hoby’s translation of Castiglione’s Covrtyer decades earlier in 1561, which also bears Harvey’s extensive annotations and forms part of the Archaeology of Reading corpus.

Multiple evidences of provenance are preserved in Harvey’s Tusser, two of which merit particular note. The first is that of the bibliomane Richard Heber (1774-1833), whose collection of early English verse and drama was the stuff of legend even in his own lifetime, filling over a dozen volumes of sales catalogues at the end of his life. The loss of the book to the anonymity of the auction houses caused Virginia Stern to cite the location of the volume as unknown in her Gabriel Harvey: His Life, Marginalia and Library (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1979), 238. Fate would conspire otherwise, however; Princeton University Library was the successful bidder in the December 2015 auction of Robert S. Pirie’s tremendous private collection of early English books, where Harvey’s Tusser had resided for many decades, making possible its last-minute inclusion (and the first comprehensive transcription of Harvey’s dense marginalia) within the Archaeology of Reading corpus. See Andrew McRae, God Speed the Plough: The Representation of Agrarian England, 1500-1660 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1996), 135-68. Andrew McRae, “Tusser, Thomas;” and Patricia Brewerton, “Denham, Henry,” in Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, online edn, Jan 2008, http://www.oxforddnb.com. AOR Bookwheel Blog Entries: Kristof Smeyers, “Sensation in the Margins” & “Diaspora/Rhyme;” Jaap Geraerts, “Harvey Reading Verse.”

― Earle Havens