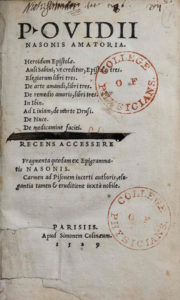

Ovid [Publius Ovidius Naso], Amatoria, opera. (Paris: Simon de Colines, 1529).

Ovid [Publius Ovidius Naso], Amatoria, opera. (Paris: Simon de Colines, 1529).

212 + 210 leaves, 18cm (8vo)

London, Royal College of Physicians Library D1/20-a-13.

Although Cicero and Virgil often feature heavily in discussions of Renaissance and early modern Latinity, the rediscovery and resurgence of Ovid is also a notable feature of Renaissance literary activity. Like the large collected edition of Cicero’s works that Dee inscribed at the same time, this smaller octavo collection of Ovid’s letters and love poetry was the product of a Parisian press. Simon de Colines was the contemporary and, for a time, the fiduciary of the press of Robert Estienne. While both were instrumental in printing and reviving classical texts for an English audience, Colines would produce smaller, more compact collected editions of the works he produced. The combination of works in these two volumes follows the pattern established by Aldus Manutius’s three-volume edition of Ovid’s collected works (1502–3), an arrangement that was openly pirated by French printers in Lyon less than three years after its completion.

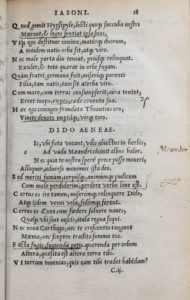

The date of this book’s acquisition, 1546, places it in the same context as the Cicero volumes in Dee’s library: his fellowship at Trinity College, Cambridge. Yet while similar tendencies towards marking and defining passages can be found in both the Cicero and Ovid editions, a large part of the Ovidian works in the book are left unannotated, and those that Dee did mark offer little descriptive detail as to why he did so. The letters of the Heroides, Ovid’s famous and cutting mock letters from mythological heroines to their husbands and lovers, is thoroughly underlined and marked with indexing words and symbols, and the books of the De arte amandi and Remedio amoris, both texts with a long and complex literary reception, received similar treatment. These particular texts were frequently taught in grammar schools, the elegance of Ovid’s style and composition usually taking precedence (particularly in the case of the Heroides) over any questionable moral issues the texts contained.

See A. Moss, “Ovid in Renaissance France: A Survey of Latin Editions of Ovid and Commentaries Printed in France before 1600,” Warburg Institute Surveys VIII (London, 1982); K. Amert, “The Intertwining Strengths of Simon de Colines and Robert Estienne,” in The Scythe and The Rabbit: Simon de Colines and the Culture of the Book in Renaissance Paris, ed. R. Bringhurst (Rochester, NY: 2012).

― Neil Weijer