Thomas Walsingham, Historia brevis (London: Henry Bynneman, 1574) [Bound with Ypodigma Neustriae (1574)].

Thomas Walsingham, Historia brevis (London: Henry Bynneman, 1574) [Bound with Ypodigma Neustriae (1574)].

[12], 267, [85] pp., 33 cm (fo).

Royal College of Physicians Library, 10552-2 D1/17-c-11.

The life of Thomas Walsingham (1376-1422) bookends that of Matthew Paris as the high-water mark of historical production at the monastery of St. Albans. During his tenure at the monastery between 1380 and 1422, he compiled commentaries on classical authors, including Ovid and Dictys of Crete, as well as historical works which updated and amended the chronicles of his predecessors. While the Chronica maiora is the most well-known and detailed of his histories, Walsingham compiled several other works, including the two in the present volume.

The first of these, the Historia brevis, narrated the successions of English kings from Edward I (where Matthew Paris’s narrative left off) and thus covered another critical period in English history for Elizabethan England. While Matthew Paris offered a contemporary account of the disputes between King John and his baronage, Walsingham’s history did the same for the beginnings of dynastic struggles between the houses of York and Lancaster which would ultimately end (albeit some sixty-three years after Walsingham’s death) with the ascent of the current ruling dynasty, the Tudors.

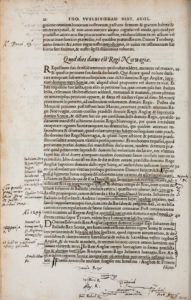

Dee’s interest in these later histories, as evidenced in his underlining of names and figures, lay in the mentions of the Mortimer, the de Burgh, and especially the Claire families, all of which had ties to lands in Ireland and Wales. As the antiquarian William Camden observed in 1573, Dee’s library contained a number of charters and deeds from these families, dating around the times of the readings. Dee would later note in his Compendious Rehearsal that these “evidences of diverse Irelandish Territories” traced the origins of their landholdings and also, perhaps, directed his reading of this book.

See B. S. Robinson, “‘Darke Speeche’: Matthew Parker and the Reforming of History,” Sixteenth-Century Journal 29:4 (1998), 1061-83; E. Evenden, Patents, Pictures and Patronage (Aldershot, 2008), esp. pp. 135-40; W. Sherman, John Dee (Amherst, MA, 1995), pp. 148-200; Roberts and Watson, Catalogue pp. 17-18, and List D, pp. 184-87.

― Neil Weijer