A Biography of Gabriel Harvey

Gabriel Harvey was born in 1551/2 in the prosperous market town of Saffron Walden, Essex. Situated between London and Cambridge, the town took both its name and its prosperity from the local cultivation of the saffron crocus, used to make a particularly valuable yellow dye. Harvey’s father, John, was a farmer and rope maker, a member of the town corporation, and wealthy enough to afford Gabriel and his younger brothers the classic education of the upwardly mobile, provincial middling sort—namely, the local grammar school and then university at Oxford or Cambridge.

After receiving his BA in 1569 from Christ’s College, Cambridge, Harvey became a fellow of Pembroke Hall in 1570. His academic career was marked more by periodic eruptions of professional backbiting than by a peaceful academic life or any major scholarly achievement in print. In fact, Harvey’s scholarship, indebtedness to the contemporary logic and rhetoric of Peter Ramus, and consequent disparagement of the Aristotelian curricular paradigm, provided much ammunition to his more conservative detractors. Personal connections forged at Cambridge offered him entries into high literary and political circles, particularly through his enduring friendship with the poet Edmund Spenser. In particular, the two friends shared a concern for the current state of poetry in England; Harvey made the spectacular claim to be the first to use the hexameter in English vernacular poetry.

Harvey entertained political as well as literary and intellectual ambitions. Influence and fame in England under Elizabeth I may well have been the preserve of an aristocratic elite, where the great offices of state were monopolized by a few great landowners, but that elite could also help to advance the more promising “new men” of ability and achievement through personal patronage. Harvey had owed election to his fellowship at Cambridge partly to the support of the scholar-politician and diplomat Sir Thomas Smith, another native son of Saffron Walden and close student of the expressive powers of the English language. Throughout his public career Harvey actively sought out connections within the upper echelons of the Elizabethan court and, by 1577, had found employment as a “professional reader” (a kind of scholarly adviser) to the legendary poet Sir Philip Sidney, nephew of the Earl of Leicester.

It became Harvey’s job to read Livy’s ancient history of Rome and to expound upon its most enduring historical lessons in the company of Sidney and others, extracting the most practical, pragmatic lessons one could learn from classical history in order to apply them to the immediate geopolitical context of the present day. Harvey’s own political aspirations reached their zenith in 1578 as talk grew of a role on an important diplomatic mission to the Holy Roman Emperor. Harvey found himself in the presence of Queen Elizabeth on two separate occasions (she even allowed him to kiss her hand on a Royal Progress), which were marked by Harvey’s Latin verses Gratulationes Valdinenses. Little came of these instants of great promise, however, and, in search of a better living than that afforded to a fellow of a Cambridge college, Harvey moved to London in the 1580s to take up practice as a civil lawyer in the ecclesiastical courts.

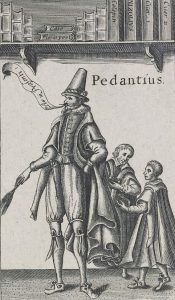

Shortly after his London move, he became unwisely embroiled in a very public and utterly personal pamphlet war with the much funnier and more pleasing satirist Thomas Nashe. Nashe’s unsmiling assault on Harvey’s character seems to have satisfied one of several stereotypes current at the time: that of the presumptuous, social-climbing tradesman’s son strutting through the streets of London wearing ludicrous Venetian fashions who could not help but make a fool of himself simpering over the queen’s royal presence. The controversy had ended by the time of the so-called Bishop’s Ban of 1599, whereby the Archbishop of Canterbury and Bishop of London clamped down on printed satire; but to be on the safe side the ban ordered that “all Nasshes and Doctor Harvyes books be taken wheresoever they maye be found and that none of theire books bee ever printed hereafter”. In many ways Harvey’s reputation has never recovered. The only surviving portrait of him is a caricature: an unfortunate woodcut from Nashe’s “Have with You to Saffron Walden” depicting a weak-eyed man shuffling in a desperate hurry to get to a toilet.

Shortly after his London move, he became unwisely embroiled in a very public and utterly personal pamphlet war with the much funnier and more pleasing satirist Thomas Nashe. Nashe’s unsmiling assault on Harvey’s character seems to have satisfied one of several stereotypes current at the time: that of the presumptuous, social-climbing tradesman’s son strutting through the streets of London wearing ludicrous Venetian fashions who could not help but make a fool of himself simpering over the queen’s royal presence. The controversy had ended by the time of the so-called Bishop’s Ban of 1599, whereby the Archbishop of Canterbury and Bishop of London clamped down on printed satire; but to be on the safe side the ban ordered that “all Nasshes and Doctor Harvyes books be taken wheresoever they maye be found and that none of theire books bee ever printed hereafter”. In many ways Harvey’s reputation has never recovered. The only surviving portrait of him is a caricature: an unfortunate woodcut from Nashe’s “Have with You to Saffron Walden” depicting a weak-eyed man shuffling in a desperate hurry to get to a toilet.

Well before the conclusion of his printed contretemps with Nashe, by the early 1590s, Harvey had already returned to Saffron Walden, where he remained until his death decades later, in 1631. One of his last appearances in the historical record is in a letter of petition to Robert Cecil jockeying (unsuccessfully) for the position of Master of Trinity Hall, Cambridge, then held by Thomas Preston, a man grievously ill and soon to die. Preston was succeeded by another, but Harvey’s later obscurity cannot be mistaken for failure. He had seen many of his contemporaries fail, some even executed for treason, as in the case of Henry Cuffe, another professional reader in the employ of the Earl of Essex. Harvey carried on his life quietly, and in likelihood comfortably, in the town of his birth, surrounded by his great library of books.

― Matthew Symonds and Earle Havens