Geoffrey of Monmouth (fl. 1135), Britanniae vtriusque Regum et principum origo & gesta insignia [Historia regum Britanniae] (Paris: Iosse Badé, 1517).

Geoffrey of Monmouth (fl. 1135), Britanniae vtriusque Regum et principum origo & gesta insignia [Historia regum Britanniae] (Paris: Iosse Badé, 1517).

[8], CI, [1] leaves, 4⁰

Oxford, Christ Church Wb.5.12.

The printing of this text, commonly known today as the Historia regum Britanniae (History of the Kings of Britain) ushered in a new chapter in the long and infamous story of Britain’s ancient historiography. The Historia, which narrated the pre-Roman history of Britain beginning with its foundation by Brutus of Troy (a supposed great-grandson of Aeneas), was completed around 1138 by the Benedictine monk Geoffrey of Monmouth as the newly-established Norman dynasty in England teetered on the brink of a succession crisis. Through the stories of Brutus and his legendary successors, including the tribulations of king Lear at the hands of his daughters, the Christianizing of the realm under king Lucius (fl. 150AD), and the imperial splendor of King Arthur and his knights, Geoffrey propounded a vision of a noble British lineage, unquestionably free within its domain, and equal (as well as antagonistic) to their Roman counterparts.

Debate over the accuracy of Geoffrey’s work was vigorous and long-lasting. Geoffrey claimed to have translated the history from a “very ancient book in the British [i.e., Welsh] language,” a book to which (as both Geoffrey and his critics conveniently pointed out) nobody else had access. Despite criticism of both the work and its author, Geoffrey’s skill at weaving Britain’s prehistory into the gaps in Biblical or classical accounts led contemporary and successive historians to incorporate individual episodes, or at the very least his genealogy of ancient British kings, into their own works. By the end of the fifteenth century, the account of Brutus and his descendants could be found not only in the more than two hundred individual Latin manuscripts of the Historia, but also at the beginning of nearly every vernacular history of England.

Printing ushered in a new phase of this very old debate. Vernacular versions of the history were among the first texts to be printed in English, William Caxton’s 1480 edition of the Chronicles of England being the first of seven printed before 1500. The Parisian printer Josse Bade (latinized as Iodocus Badus Ascensicus) issued the Latin editio princeps in 1508, to which this 1517 edition of the Historia added only minor corrections. Both were the work of Ivo Cavellatus, who encountered manuscripts of the work in horrible condition at the College of Quimper in Paris and collated them with others around the city.

The Renaissance penchants for book-hunting and criticism of sources gave rise to a new generation of protagonists in the debate over Britain’s past. Most notable among the critics was the Italian scholar and Papal legate to England, Polydore Vergil (1470-1555), whose Anglica Historia (1535) laid bare the discrepancies between the Galfridian account and the histories of classical authors, urging the English to leave such stories to old maids rather than reputable historians.

Polydore’s challenge was met by a generation of English and Welsh antiquaries who sought to validate Geoffrey’s account (or at least parts of it) by resorting to the trove of historical material unearthed from England’s monasteries, topographical evidence, and often, their knowledge of the descendant of Geoffrey’s “ancient British” tongue—the Welsh language. Led by the ambitious Englishman John Leland (1503-52), their approaches to recovering the past would influence nearly all historical projects in early modern England.

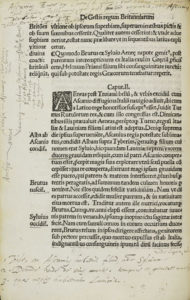

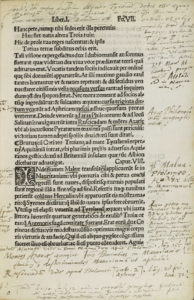

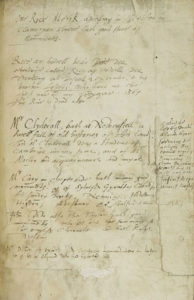

John Dee, then, could not help but bring his own linguistic and bibliographic skills to bear upon this debate. The flyleaves of his copy of Geoffrey’s Historia introduces the debate with excerpts from a standard reference, John Bale’s index of famous British authors (1559, Dee’s copy is Christ Church, Oxford Wb.5.13). As did the antiquaries before him, Dee hunted through the text of the Historia for genealogical and lexicographical connections between Britain’s ancient kings and places and their reflection in the parlance of his own day. Other of his notes reveal that his copy was likely collated against both Latin and vernacular manuscripts containing accounts of Britain’s first kings. Finally, the flyleaves of the book also make reference to Dee’s own search for copies of ancient histories and notices of his own family genealogy. The versatility and flexibility with which Dee approached his copy of the Historia is instructive, as it suggests not only how, but why, the then ancient narrative of Britain’s legendary monarchs retained a place in England’s historical, antiquarian, and social imagination.

See also M. Reeve, ed., and N. Wright, trans., The History of the Kings of Britain (2012); T. D. Kendrick, British Antiquity (London: 1950) J. Levine, Humanism and History (Ithaca, NY: 1987); N. Weijer, AOR Bookwheel Blog Post, “Dee’s Mistakes.”

― Neil Weijer