Thomas Walsingham, Ypodigma Neustriae (London: John Day, 1574) [Bound with Historia brevis (1574)].

Thomas Walsingham, Ypodigma Neustriae (London: John Day, 1574) [Bound with Historia brevis (1574)].

[4], 39, 38-146, 141-199, [5] pp., 30 cm (fo).

Royal College of Physicians Library, 10552-2 D1/17-c-11.

[For biographical details about Thomas Walsingham, see the essay for the Historia brevis.]

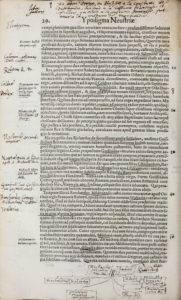

In contrast to the Historia brevis, the Ypodigma Neustriae highlights Walsingham’s interest in connecting the present to the distant past. His last known work, the Ypodigma begins with the histories of the first Norman dukes from Rollo and his Danish ancestors first recorded in the early eleventh century by Dudo of Saint-Quentin, traces their lineage through the Norman conquest of England and the establishment of the Plantagenet dynasty, and concludes during the reign of Henry V, whose triumphs over the French were commemorated in the dedication to the chronicle.

Like the Flores historiarum, the present editions of both of these works were the products of Archbishop Matthew Parker’s scholarly circle and the publication project he undertook through it. These efforts intensified in the early 1570s, possibly due to increased tension in the wake of the Ridolfi Plot as well as Parker’s own eagerness to publish the fruits of his collection. John Day, who printed the Ypodigma (and may have collaborated with Bynneman on the Historia brevis) was central to the printing of Parker’s scholarship, producing Anglo-Saxon as well as English translations undertaken by Parker and his orbit.

Dee’s reading around the antiquity of Normandy in the Ypodigma, along with his investigations into the ancient history of the Britons (via Geoffrey of Monmouth) and the Trojans (through the supposed eyewitness accounts of Dares the Phrygian and Dictys of Crete), never directly intersected with Parker’s efforts. During the same time, however, Dee was perhaps most intently compiling materials for his writings on English economic and imperial expansion. As a set, then, the historical works in the AOR corpus underscore the degree to which antiquarianism, book collecting, and historical investigation were central to a wide range of personal, professional, and political concerns in Elizabethan England.

See B. S. Robinson, “‘Darke Speeche’: Matthew Parker and the Reforming of History,” Sixteenth-Century Journal 29, no. 4 (1998): 1061–83; E. Evenden, Patents, Pictures and Patronage (Aldershot, 2008), esp. pp.135–40; Sherman, John Dee (Amherst, MA, 1995), pp. 148–200; D. Owens, AOR Bookwheel Blog Post, “John Dee’s Historical Comparisons: the Mystery of the Liber Gallicus.”

― Neil Weijer