On Readers and Repetition

The complexity and density of the marginalia found throughout the Domenichi/Guicciardini volume makes it difficult to describe—let alone categorize—Harvey’s peculiar manner of annotation. As I mentioned in an earlier post, he doesn’t seem particularly interested in responding to the printed text. Originally, I referred to Harvey’s practice in this instance as that of writing a “manual,” ideally for the training of a gentleman of the court. I still feel that this is the case; that is, I feel that Harvey intended for his annotations to be not only read but also used by his reader as an aid to becoming a more virtuous person.

One indication that the text is intended to be used can be found in the frequent repetition of names, book titles, and concepts in the form of digestible phrases, almost always in Latin. Harvey himself explains the pragmatic scope of this repetition in one of the few marginal notes that contains some degree of reflection on the activity of annotating.

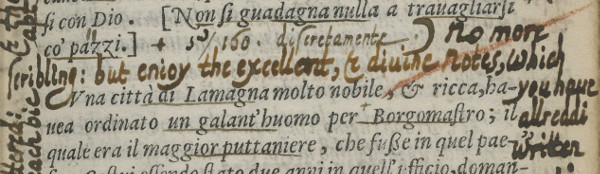

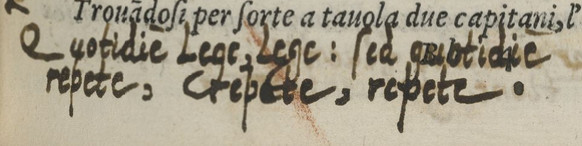

This entire page contains marginalia calling on the reader in English to embrace repetition. Immediately in the top margin we find:

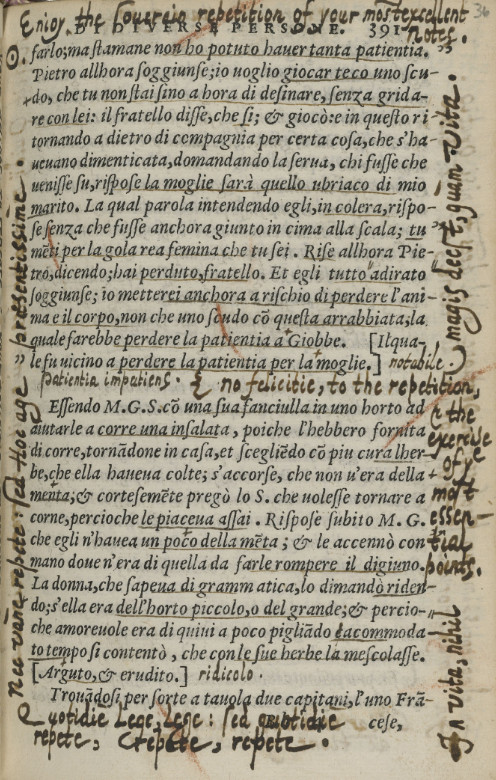

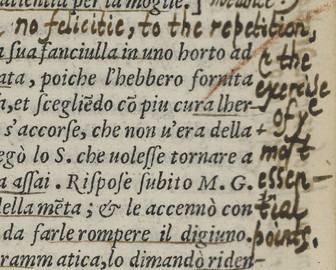

Farther down the page in the middle of the text, Harvey reminds his reader that happiness is not necessarily the goal of such activity. Instead, repetition is an essential form of exercise.

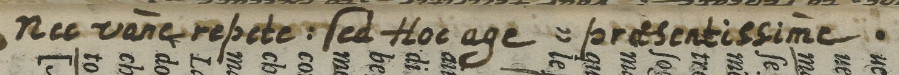

Exercise, practice, habit, self-improvement—these are crucial elements in Harvey’s manual, and the words themselves return frequently. And in case the reader hasn’t yet learned this message by heart, the remaining Latin phrases on this page offer further exhortations. In the bottom margin, we find:

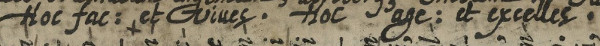

The usage of the imperative mood offers further evidence of the practical nature of these marginalia. Here and elsewhere, the verbs cease to describe the world and begin to tell the reader what to do. Indeed, in the left margin of this same page, Harvey orders his reader to engage actively with the text:

Repetition in itself is not necessarily a useful activity; for it to be most effective, one must be “present”—that is, reading and repeating with with one’s full attention. This note also includes a phrase that will appear occasionally throughout the volume: Hoc age (Do this).

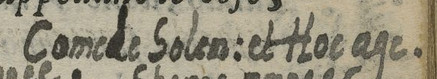

Unlike in other instances of the word “hoc,” here Harvey capitalizes the letter h, lending a more abstract sense to the meaning of “this.” Rather than directing his reader towards a specific act, Harvey seeks a specific behavior and attitude: Do This—not in vain, but with as much presence as possible; Do This—and live well; Do This—and devour the sun.

As a result of this insistence on reading, rereading, and contemplating marginalia as a means to practical ends, Harvey seems to have produced a sui generis form of writing. For lack of a better word, I have been calling it a manual, but the descriptive power of this label will always be partial. Much work still remains to be done on the form of the notes as a whole, which also involves making sense of the time periods in which certain marginalia were written. I mentioned in my last post that we can approximate dates ranging from 1580 to 1608. In fact, Harvey seems to have spent so much time on this project that he even had to remind himself to stop “scribbling” and simply enjoy the work that he had already produced.