Happy Fri-Dee, everyone.

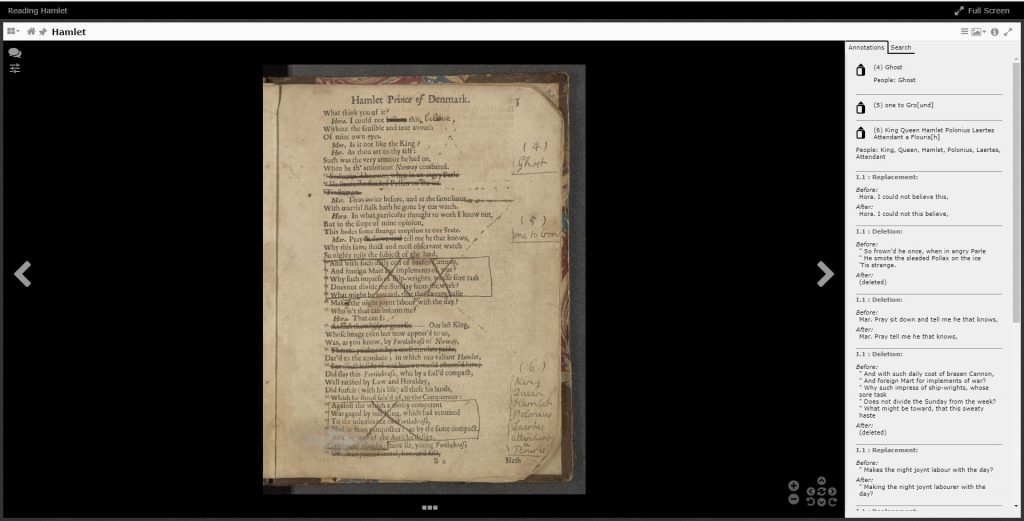

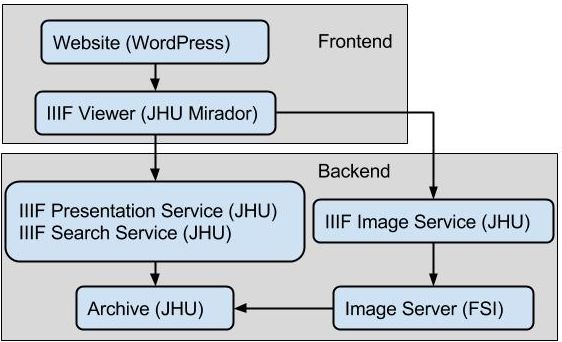

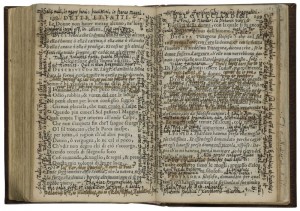

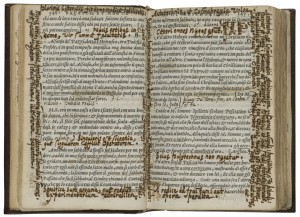

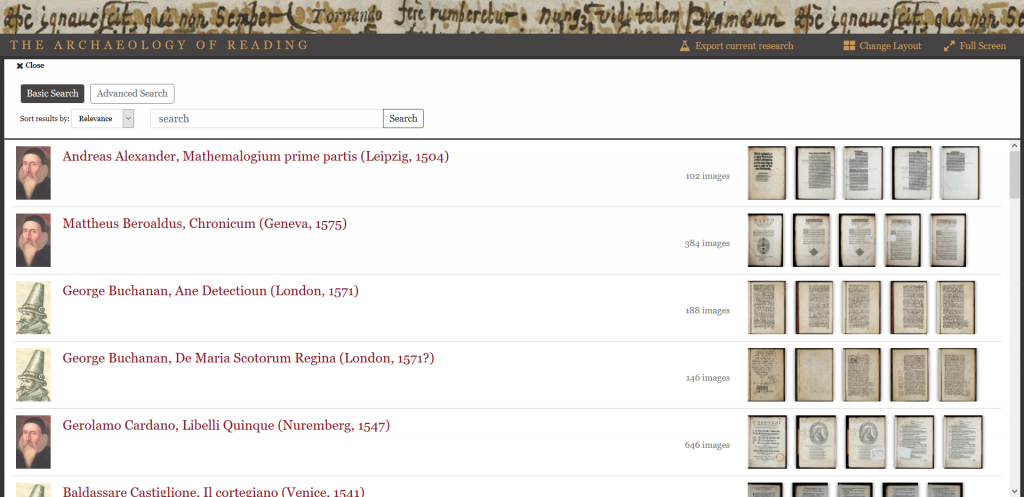

After much transcribing, tinkering, and typing, we’re happy to unveil the fully-updated Archaeology of Reading viewer! We hope it provides a functional and sharp facelift to the Gabriel Harvey books, which are now joined by the 23 volumes annotated by John Dee. Now you can finally see what we’ve been blogging about for the past year and a half. Feel free to stop reading at this point, click on the red “Go to AOR Viewer” button above on the masthead, and dive in!

While more detailed descriptions of how to use the viewer are available here, it might be good to call out a few particularly useful features. While all the books appear alphabetically by author in the gallery, the icons next to them will let you know who read which one.

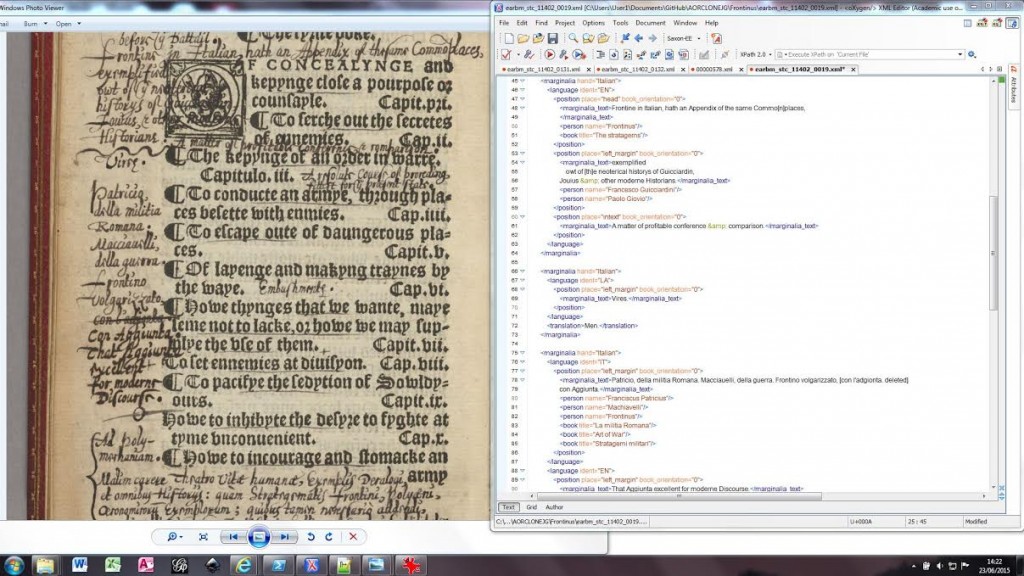

Secondly, the tagged materials in each note now appear as live links, which can be used to initiate searches within and, in some cases, outside the viewer. Clicking on any one will give you the option to search for it within the book or the entire AOR corpus.

For books and people (documented ones anyway) mentioned in the notes. you also have the option to go to the record preserved in the Universal Short Title Catalog (USTC) or their International Standard Name Identifier (ISNI). As we said, you won’t be able to do this for the legendary British monarchs found in Geoffrey of Monmouth, but you can still search for them in other places (as Dee did when he read historical books)

Lastly, our viewer now features stable URIs for each image in the corpus, as well as some states of the viewer (such as searches). These can be pasted into a browser to immediately refer back to the page you were on, and can also be exported as a list by using the “Export Current Research” button in the top right of the header. You’ll be able to select the pages or searches you want to save and annotate them as a list of links in HTML, or, if you’re more graphically inclined, as a Distributed Scholarly Compound Object (DiSCO) in RMap. If the last part of that sentence didn’t make sense, don’t worry, but we hope that RMap will give the opportunity for searches, findings, and other observations to layer onto each other, and for researchers to see how this particular group of books is being read currently (meta-AOR).

Our WordPress site has also undergone some modifications. Descriptive essays for all of the books in the corpus, as well as the larger libraries that they were drawn from are now available in the “Books and their Readers” tab. Click through them to learn more about the tale of two libraries this project now tells.

A huge note of thanks is due to those of you who beta tested a version of this site over the holidays. We were able to do some last-minute adjustments to the search bar, in particular, to make the resource more easily navigable. The viewer wouldn’t look as nice as it does without the efforts of our resident technologists at the DRCC, and the creative eye of Cathy Shaefer and her team at SPLICE Design Group.

We hope that you enjoy the viewer as much as our sixteenth-century readers would have. We’ll be adding more video and teaching content to the site over the upcoming weeks, so watch this space for more!