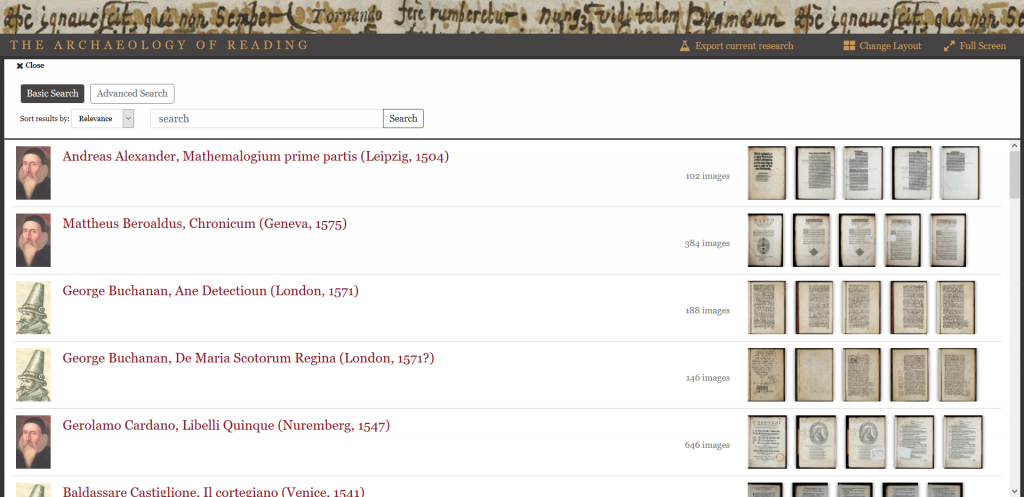

At the most recent conference of the Renaissance Society of America (RSA) in New Orleans, I planned to speak about the difficulties in writing a more general history of historical reading practices and offer several possible solutions. More specifically, I wanted to explore various strategies which can be employed in order to examine similarities and differences in the reading practices of Gabriel Harvey and John Dee. Sadly, though, a winter storm prevented me from leaving Princeton and ultimately from giving my paper as I only arrived in New Orleans on Friday afternoon (hence missing out on most of the conference). Although my paper was unlikely to revolutionize the field, some of the issues I address are relevant to those working on the history of reading. I therefore would like to make use this space to briefly discuss one particularly vexing problem, namely the difficulty of incorporating topical marginal notes in our analysis.

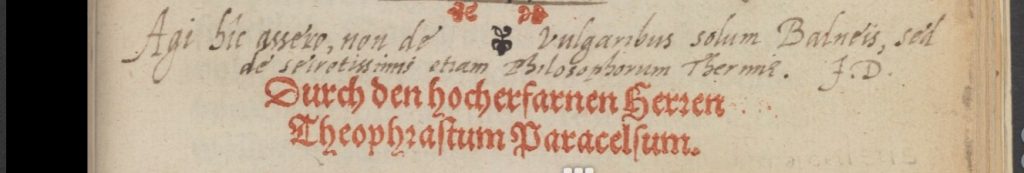

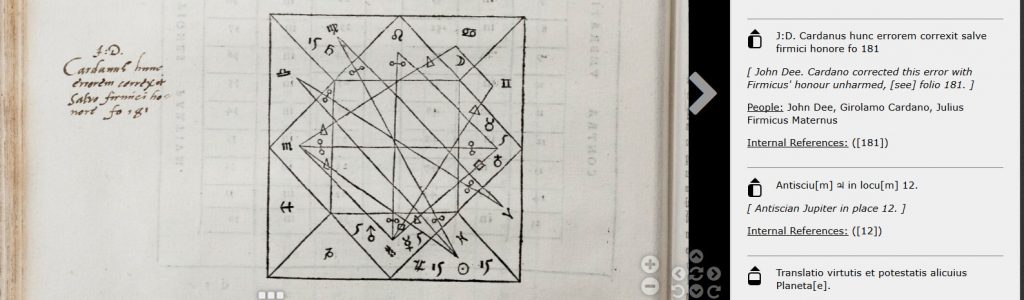

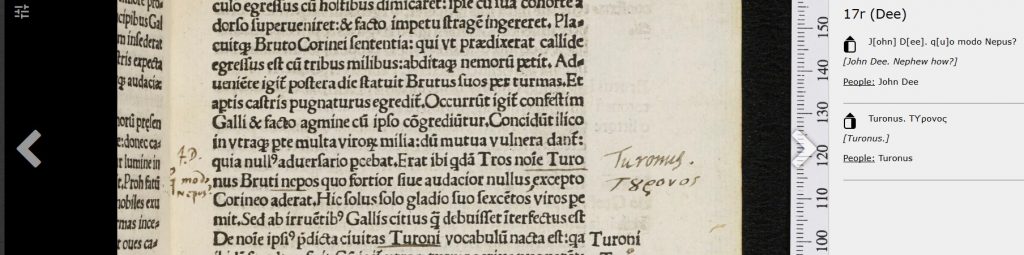

According to Bill Sherman, a ‘topical note’ are those marginal notes which acted ‘as a concise key to the topic of a passage’ (Sherman, Dee, 81). In general these notes consist of a just few words, often copied from the printed text, which indicate the main topic of a section. It is not that these topic notes completely escape the possibility of scholarly analysis: at their very core they show the particular intellectual interests of a reader. When having the advantage of working with a known reader, such as Dee and Harvey, knowledge of the historical context is of invaluable help when trying to make sense of such annotations. As Sherman remarked, ‘Dee’s notes in these passages [in some medieval books] are rarely interesting in themselves…but their value lies in the fact that he consistently drew attention to the material that would inform his own historical and political discourses’ (Sherman, Dee, 91).

At the same time, even when equipped with (detailed) biographical information about a reader, the lack of interpretation on the part of the reader in turn renders topical notes difficult to interpret for scholars. Hence our inclination to focus on those marginal notes which are more verbose and informative in nature. However, such marginal notes represent only a small minority of the annotations that decorate the pages of most early modern books. Due to our focus on the relatively small number of interpretative notes, our research tends to be rather impressionistic in nature. But in general, topical notes abound: they litter the pages of the books owned by John Dee, while even a substantial number of annotations made by Gabriel Harvey, unusually verbose when annotating his books, are of the topical kind.

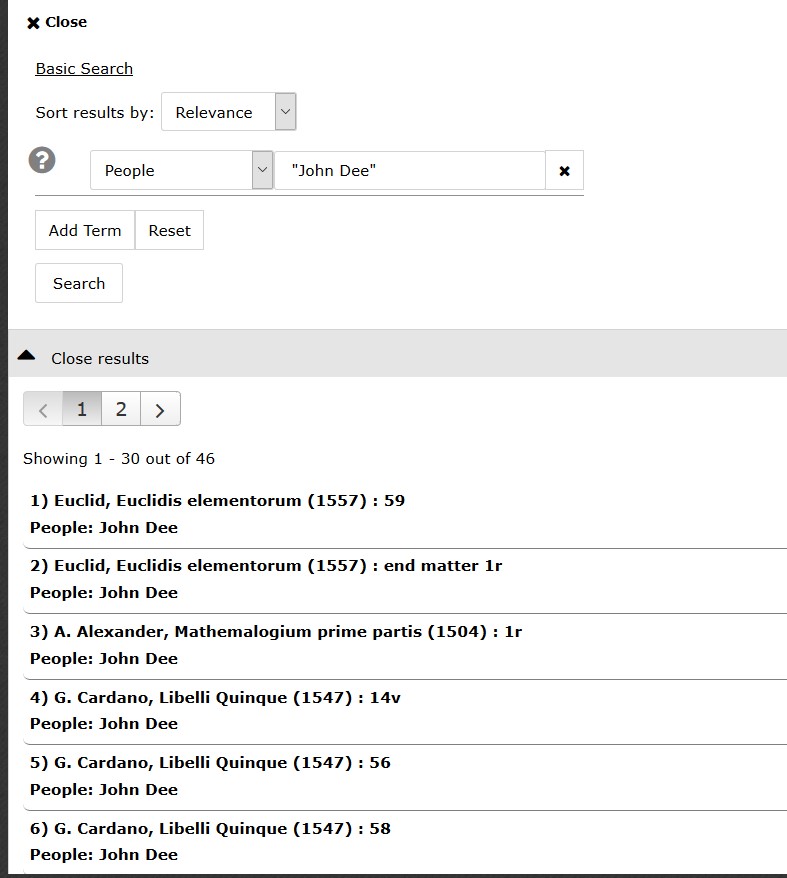

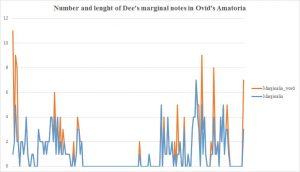

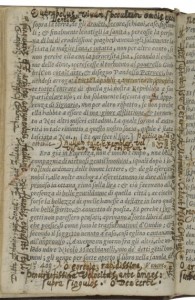

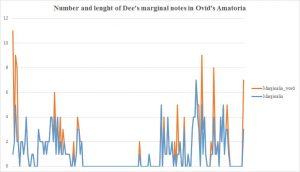

Data-driven approaches can be used to show the proliferation of topical notes and might offer a solution to overcome, at least partly, their limitations. A particularly revealing case is Dee’s copy of Ovid’s Ars Amatoria (Paris, 1529). Dee only annotated this book sparsely: he scribbled 181 marginal notes in the margins while he underlined approximately 4000 words of the printed text. Moreover, the average length of these marginal notes was 1.3 words, meaning that the majority of these notes just consisted of one word.

This is very little, even when compared to other books annotated by Dee and Harvey (bear in mind that the transcription work is ongoing and the figures in this overview are based on the statistics generated in late March 2018).

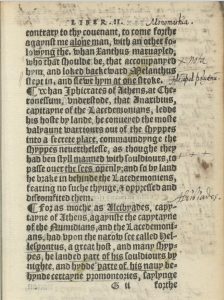

Some books clearly stand out. Dee’s copy of Euclid’s Elementorum, for example, only contained 25 annotations, but with an average length of almost 24 words (23.96). This average is greatly inflated by the appearance of a couple of lengthy marginal notes at the start of the book. The numbers relating to Dee’s copy of the Pantheus’ Voarchadumia are skewed as well: Dee interleaved this book with blank pages onto which he copied the text another tract by Pantheus, the Ars Metallicae. Because these interventions are treated as marginal annotations, the average number of words is greatly inflated. Harvey’s copy of Livy’s History of Rome, boasts a similar average (21.8 words), but based on an astonishing number of 854 annotations. Although massive annotations, such as one which consists of a staggering 718 words, helps to increase the average, the number of annotations which consists of one word are extremely limited: just 17 out of 854 annotations (almost 2%).

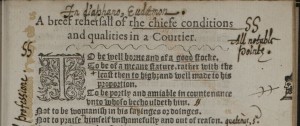

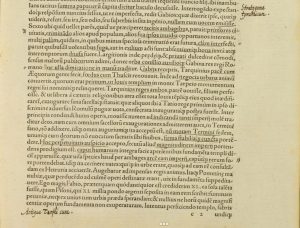

(Topical notes in Livy’s Ab urbe condita, p. 27, and Frontinus’ Strategemes, Gii).

In general, Harvey’s annotations were lengthier than those of Dee, as visible in the table above: Harvey’s average of 12.6 words against Dee’s average of 3.5 words.

Let’s return to the example we started with, Dee’s annotations in Ovid’s Ars Amatoria, and have look at the content of these short marginal annotations. When creating a list of the words and the frequency with which they appear, the results are everything but surprising: number one on the list is the word *drumroll* amor (or its declensions), which is mentioned 31 times. In the vast majority of cases, the marginal note solely comprises the word ‘Amor’. What to do with these marginal notes? Close reading is one possibility: which passages did Dee mark with this word and, just as significantly, which passages were not indicated by Dee in this manner. Such an analysis can be expanded by including other books which contain marginal annotations with the word ‘amor’. Such a ‘thematic’ search returns several hits for marginal notes in Cicero’s Opera and Quintilian’s Instititionum and can reveal a reader’s interest in a particular topic across his or her library.

Another, data-driven approach, would be to employ statistical analysis. This is a strand of AOR that we started to develop near the end of the first phase of the project (2014-6) which focused on Gabriel Harvey. Our approach is based on the creation of concept groups, consisting of words which are related to a specific topic, including war, kingship, eloquence, books, action, etc, and which appeared with a certain frequency in Harvey’s marginal annotations. After that we, and by we I mean professional statisticians, calculated whether or not there existed statistically significant correlations between concept groups. That is to say, the extent to which words which are part of one particular concept group appear in conjunction with words that are part of another. In this way, we can discern whether particular topics of interests were related to one another. As such, we are primarily interested in the intellectual patterns that appear in the marginal notes, not in the numbers generated by the statistical analysis themselves.

Although at present it is impossible to subject Dee’s annotations to such an analysis, simply because the transcription work is ongoing, we will be able to do so in a couple of months. By means of thematic searches and data-driven approaches such as statistical analysis, it might be possible to include some topical marginal notes into our scholarly investigations. Such data-driven approaches do not necessarily yield information about individual marginal notes: one-word notes, for example, cannot reveal a correlation between concept groups. However, topical notes are included in concept groups and hence figure in a larger thematic analysis.

We might be even able to expand the current statistical analysis: what happens when we start to study the correlation between books, people, and concept groups? Another possibility is to check the names of the people mentioned in marginal notes against the index of a particular book. Which people were and were not singled out by our readers? I mention these possibilities in order to make clear that there are strategies for the inclusion of topical notes in our analysis. Invariably, such strategies are time-consuming and will require a lot of work from the scholar. However, they might enable us to include a larger number of marginalia in our analysis and to get a more rounded understanding of historical reading practices and strategies.