Annotated Books at UCLA: Wider Applications of the AoR Schema

This guest entry comes from Philip Palmer, Head of Research Services at the Clark Library at UCLA. Philip writes about his experience using the AOR schema to encode transcriptions of annotated books held at UCLA

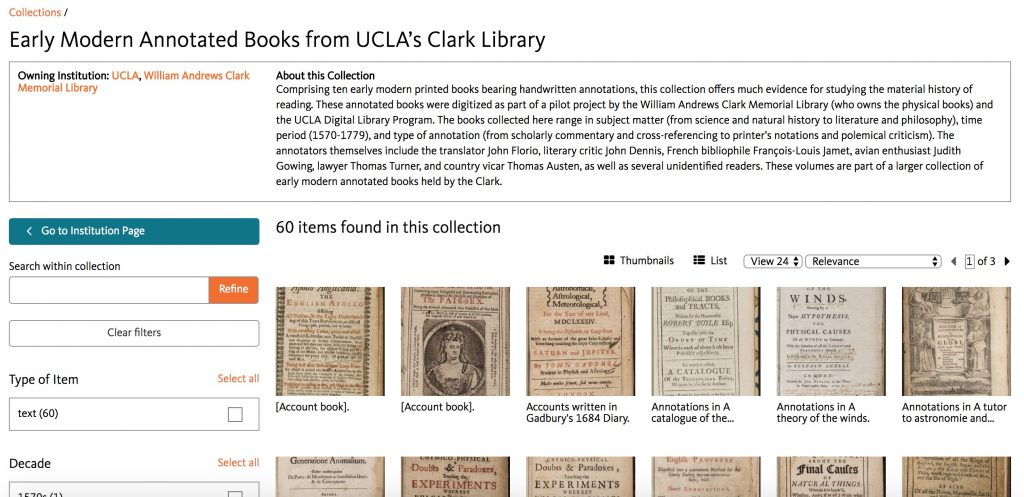

In July of 2014 I started a CLIR postdoctoral fellowship at UCLA’s Clark Library on the subject of “Manuscript Annotations in Early Modern Printed Books.” Less than a month into my postdoc The Archaeology of Reading in Early Modern Europe (AOR) project was announced, and naturally I was excited about potential discussions and collaborations with Earle Havens and his team. The Clark hosted a symposium on annotated books in December of that year, and both Earle and Matthew Symonds were in attendance. At this symposium an international group of scholars, librarians, and curators discussed various topics related to the study and curation of early modern manuscript marginalia; the symposium also coincided with the beginning of a pilot project to digitize ten annotated books from the Clark Library’s collection (since expanded to 60 books from our ongoing NEH digitization project, about which more info to come below). Since the symposium, the AOR team was generous to meet with me about the XML schema they developed and encouraged me to adapt it to the annotated books digitized at UCLA.

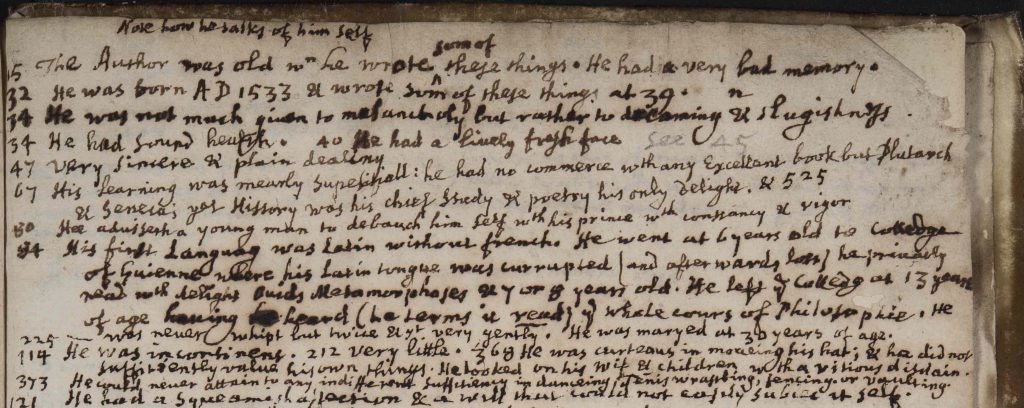

One of the main differences between the AOR corpus and the annotated books digitized at UCLA is the latter’s more variable range of annotators and annotation types. Several of the annotators are anonymous and most are somewhat obscure, with only one from the original ten books being a canonical writer (the playwright and literary critic John Dennis). None of these readers annotated more than one book in the group of ten, unlike the focus on two specific readers in AOR. The Clark readers also take many different approaches to their annotations. A copy of Sir Thomas Browne’s Pseudodoxia epidemica (2nd ed. of 1650) annotated by a seventeenth-century English lawyer comprises a complex layering of cross-references to work by Browne and other contemporary scientific texts. Being one of a handful of copies bearing errata corrected in the hand of John Florio, a copy of the 1603 English translation of Montaigne’s Essayes contains marks and marginalia made by a reader in the 1680s—a reader preoccupied with how Montaigne “talks of himself.”

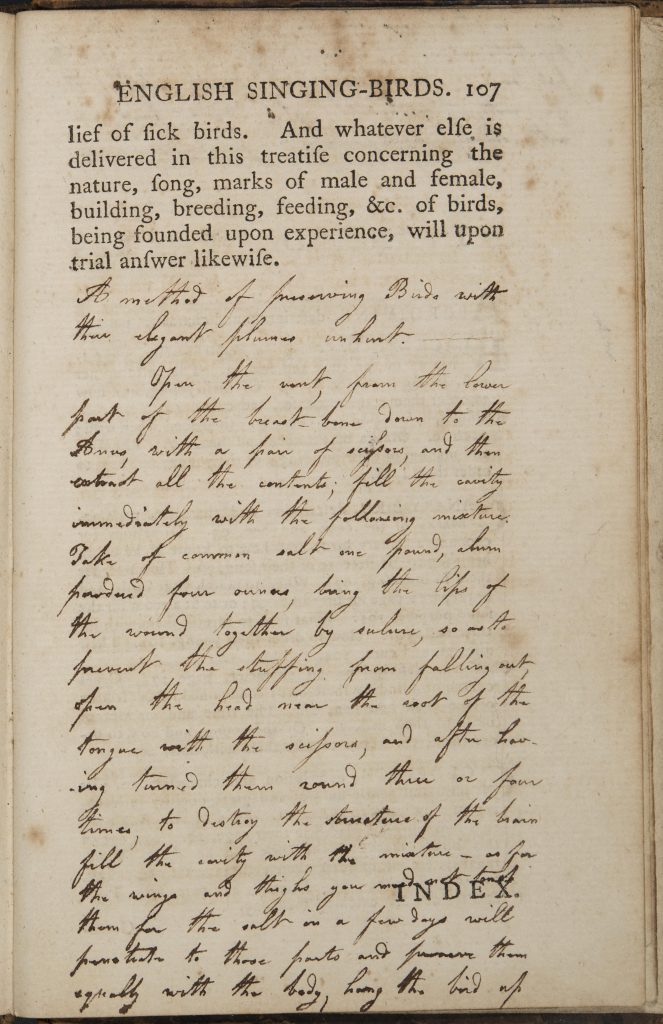

Another book in the UCLA corpus—Richard Allestree’s The Art of Contentment (1675)—features casting-off marks and marginalia made by a printer or compositor, presumably to plan a new edition of the text (though this new edition never materialized). Also digitized is a copy of Aleazar Albin’s The Natural History of English Song-Birds (1779), annotated in the early nineteenth century by an avian enthusiast named Judith Gowing, who supplemented the printed text with handwritten advice on bird-care (and a bit of taxidermy)

The six other books initially digitized from the Clark’s collection range from polemical critique in a 1724 edition of Confucius to devotional marginalia in a 1708 spiritual autobiography. In other words, there is not a common theme, method, or reader in the annotations digitized from UCLA; rather, these ten books are representative of the characteristic idiosyncrasy that historical readers brought to their material readings of books.

With support from the UCLA Digital Library to digitize these ten original volumes, the next step for our project involved transcribing the annotations. At first I explored the viability of using the Text-Encoding Initiative’s (TEI) standards to transcribe and mark-up a test set of transcribed annotations (from Roger Ascham’s A Report and Discourse of 1570). One good reason to use TEI in this case was the existence of an encoded file of the printed text of Ascham’s Report, created through the Text Creation Partnership (TCP) at the University of Michigan. The existence of this file meant all I had to do was add the text of the manuscript annotations to the existing transcription of the printed book and edit the TEI Header (the Oxford TCP website is a good place for finding such files). But one big problem is that TEI is not designed for dealing well with manuscript marginalia and cannot achieve the desired level of granularity in its encoding.

Serendipitously, it was also around this time that I met with Earle, Jaap, and Matthew to discuss the AOR XML schema and how it might be used for non-AOR projects. I was impressed with the level of detail possible with AOR markup, especially compared to the limitations of TEI for annotation encoding. While I did not plan to make too many changes to the AOR schema, there were a few small tweaks I made to accommodate the idiosyncrasy of the Clark Library annotated books. These tweaks included adding more values for handwriting type and marginalia topic, refining the way internal cross-references are encoded, and creating a new attribute for “marginalia type” within the <marginalia> element.

A month or so later the Clark Library applied for and received a small grant from the Gladys Krieble Delmas Foundation that enabled us to hire three UCLA graduate students to transcribe and encode this original corpus of ten annotated books. Two English students (Samantha Morse and Mark Gallagher) and one History student (Sabrina Smith) spent three months during the Summer of 2016 transcribing and marking-up the annotations in seven of the ten books. (The annotations in two books—Sir Richard Blackmore’s Prince Arthur and Voltaire’s Dictionnaire Philosophique—proved too voluminous for the students to finish.) On day one I offered a three-hour crash course in early modern paleography and XML text-encoding; the session was supplemented by a detailed training manual. To make the encoding process easier the Clark purchased the Oxygen XML editor software for each student.

As the transcription project was intended to pilot workflows and methods for transcribing and encoding annotated books, we were just as interested in learning about process as we were in the product of the transcribed annotations themselves. For each of the student transcribers, the beginning of each book posed difficulties, primarily related to learning an individual’s handwriting quirks. XML encoding presented a challenge as well, though the combination of the training manual, AOR schema, and Oxygen’s auto-complete feature helped our transcribers grow accustomed to the work.

This pilot project also entailed comparing the TEI-encoding of manuscript marginalia with transcriptions made according to the AOR schema. Of the seven books the students completed, two were transcribed with TEI mark-up rather than the AOR schema. In both cases, these books are available as existing TEI files through the Text Creation Partnership. In the end we concluded that the AOR schema was preferable for marking-up text to enable research on manuscript marginalia: it captures much more information than is possible with TEI, including the ability to mark-up non-textual annotations such as underlining and symbols. The one aspect of TEI-encoded annotated books I do like, however, is the ability to mark-up both the printed text and the manuscript annotations. (The AOR schema only captures the annotations themselves, though encoding an entire printed text by hand on top of the annotations is a prohibitively time-consuming enterprise!)

When the three-month transcription phase of our project ended in September 2016 there was still much additional work to be done. First I had to edit the transcriptions for accuracy, which proved to be one of the most time-consuming aspects of the project. Next I had to plan how I would display these transcriptions and digitized annotated books online without having to hire a team of programmers. We at the Clark have been fortunate to partner with the UCLA Digital Library and California Digital Library to publish the digital scans of these annotated books on Calisphere, which is a digital object platform for libraries in California, especially from the University of California campuses. The ten digitized books were published on Calisphere in mid-March 2017. But earlier in the project, when preparing the digitized books for transcription work and developing a website to showcase the transcriptions, it was necessary to upload the scanned pages to the Internet Archive, primarily so we could start exposing these annotated books to a wider audience. And since all Internet Archive digital objects now conform to the International Image Interoperability Framework (IIIF) metadata standards, it was possible for me to display our annotated books using IIIF on a custom website. (Calisphere will be using IIIF in the near future too.)

Without going into too much detail, I was able to transform automatically every XML file produced by our student transcribers (one file per annotated page, which amounted to 1,141 total files) into individual HTML pages. I then created a simple website (using nothing more than HTML, CSS, and JavaScript) showcasing those pages and contextualizing each annotated book with introductory material. With funding for further application development it would be possible to build an XML database with front-end search functionality, but for now this site does a reasonably good job presenting annotated book page images side-by-side with transcribed marks and marginalia. In the near future we hope to add our student transcriptions directly to the Calisphere website showcasing our digitized annotated books.

In fact, the Clark won an NEH grant in 2016 to digitize over 250 early modern annotated books, so the Calisphere collection will grow considerably when the project concludes in October 2018 (60 books currently available). Combined with the Clark’s recently completed CLIR grant to digitize over 300 early modern English manuscripts, the Calisphere collection will become one of the largest digital repositories of early modern English manuscript material when both projects are completed.

During all of these digitization and transcription activities it has been wonderful to work with the AOR team and watch developments in their project. As anyone who has worked on Digital Humanities projects knows, it is never a good idea to “reinvent the wheel,” and the existence/accessibility of the AOR XML schema has ensured that the Clark Library annotated book transcriptions are largely interoperable with those produced for the marginalia of Gabriel Harvey and John Dee. I encourage any other annotated books projects out there to follow our lead and re-use the AOR schema for your transcription work, as Earle, Matthew, and Jaap have been extraordinarily generous in sharing their work with the larger academic community.