This blog is written by Daisy Owens, one of the three Research Assistants working on AOR.

——————

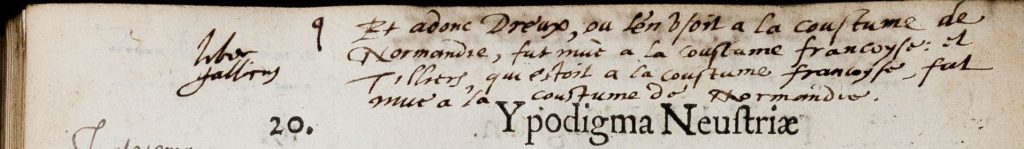

John Dee frequently refers to other books within his own collection in his marginal annotations, and by tracing these external references we can attempt to build up a picture of both how Dee read the books in his library and the connections he saw between certain texts. In his copy of Thomas Walsingham’s Ypodigma Neustriae, he unsurprisingly makes connections between this text and another historical text by Walsingham, the Historia Brevis, which is bound together in the same book. However, Dee’s most frequent external reference within his annotations of Ypodigma Neustriae are to a book which remains elusive to me, the mysterious ‘liber gallicus’.

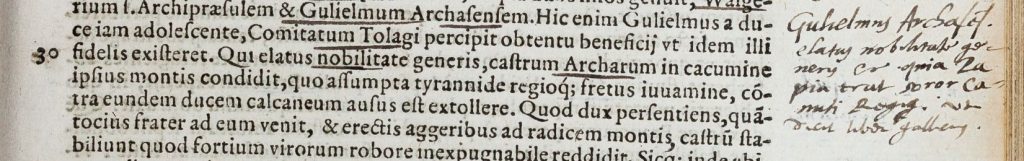

Dee makes seven allusions to a certain ‘liber gallicus’, as well as two mentions of a ‘traductio gallica’ which may refer to the same text, over a twenty page-section of Walsingham’s text approximately covering the period 933 to 1037 in the history of Normandy. These repeated references to the ‘French book’ contrast with his other connections between texts in a number of ways. Whilst in most of his external references Dee names the author, here no such helpful information is given. Even the name ‘liber gallicus’ stands out as an unlikely actual title, a feeling compounded by the fact that it always appears here uncapitalised. Though we can only speculate about the reasons behind this apparent lack of detail, the sustained comparison with Walsingham’s history suggest that this was a book of some importance to Dee.

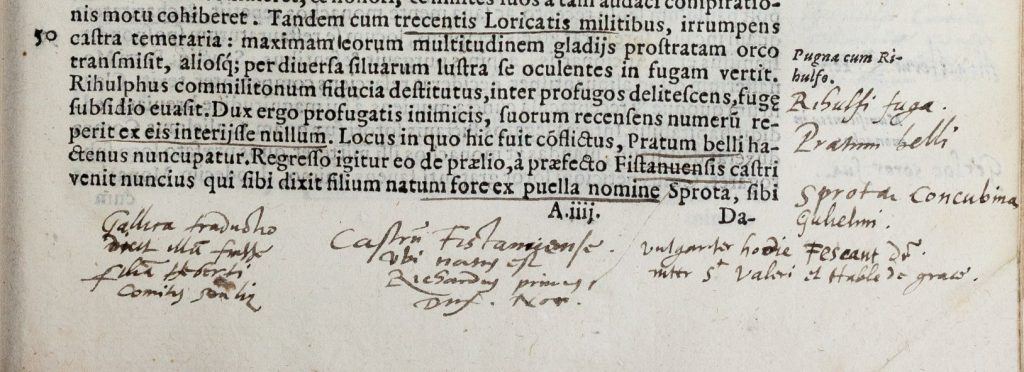

Whilst some of these references simply note ‘liber gallicus’ next to part of the printed text or Dee’s own marginalia, perhaps indicating that a particular historical episode or figure is also recorded in the French book, on occasion they appear to allude to extra information supplied in ‘liber gallicus’, or even to differences between the two texts. Beneath a reference to Sprota, the mother of Richard I of Normandy, Dee notes in Latin that ‘the French translation says that she was the daughter of Herbert, Count of Senlis’. Where Walsingham names the daughter of Duke Hugh the Great as Emma, Dee states that the French translation calls her Anina or Agnet. Whilst elsewhere Dee corrects errors in both content and grammar, marking out key passages in his copies of texts such as De Navigatione and Historie del S. D. Fernando Colombo with an approving ‘hoc verum’ or ‘verè’, interestingly here he does not indicate whether he feels one book is more reliable than the other. Judging from these annotations, he appears to value the comparison of a variety of texts, and here seems reluctant to wholeheartedly pledge allegiance to either of the accounts.

Pinning down the identity of the work Dee repeatedly references should have been simple due to the specificity of the references: I was, after all, searching for a book about a particular one hundred-year period of Norman history featuring some fairly obscure figures. However, unfortunately the precision of the historical moment was matched by the vagueness of Dee’s authorless ‘liber gallicus’ tag. After some investigation, I lined up Matthew of Paris’ Chronica Majora as a possible contender; sadly my hopes were dashed when the content of the two texts failed to correspond. I also remained preoccupied with Dee’s uncharacteristic failure to give the author’s name…

Although the identity of ‘liber gallicus’ remains a mystery to me at present, the study of Dee’s references to other texts here and elsewhere in his library opens up a number of lines of enquiry regarding his approach to the study of history and to learning and reading more broadly. Drawing on these connections, we can begin to piece together a more detailed picture of Dee’s tentative but rigorous approach to history involving a comparison of multiple texts.