For the past few days, I have gone down the rabbit hole of worldwide library catalogues in order to actualise the status quaestionis of Gabriel Harvey’s library. The last cohesive attempt dates back to Virginia Stern’s book Gabriel Harvey: his life, marginalia and library from 1979. But books are nomadic objects. Like so many early modern collections, Harvey’s books have not stayed together, and since 1979 have either moved to different shelves, some surfacing from the private depths of the bibliophile world, while others were last seen in auction catalogues before disappearing entirely.

What further complicates this task is that we can really only make educated guesses as to how many books Harvey’s library consisted of. Rough estimates range from a few hundred to well over a thousand. The corpus that I have reassembled so far (of course standing on the shoulders of Stern and others) consists of roughly 160 books of which I am confident what shelf they are currently on. They will provide a wider context for the AOR corpus.

Geographical context also applies here, as there are traces of Harvey’s library in more than twenty libraries across the world—usual suspects like the British Library and the Oxford and Cambridge college libraries but also, for example, the National Libraries of Wales and Australia, and various institutions across the United States, most predominantly the Folger Shakespeare Library and Princeton University Library. An additional complication is that catalogues of smaller libraries and collections, such as the Rosenbach Library and the collection of the Saffron Walden Museum, are often not electronically available. The diaspora of Harvey’s library is absolute: a catalogue of his books can only be provisional—we never know how many books are still unfound.

One such book that has recently become available and that already has been written about in our previous blog posts is Harvey’s copy of Thomas Tusser’s Fiue hundred pointes of good husbandrie, now residing at Princeton. In our corpus of thirteen it is not so obvious, but when zooming out to the (known) spectrum of Harvey’s whole library, Fiue hundred pointes becomes more evidently peculiar. In a collection of mostly political, historical and legal works, a practical calendar for countryside living – in rhyme! – seems out of place. Tusser’s Hundreth pointes was a popular book from the moment it was published in 1557. It was reprinted so often that the London-based publisher Richard Tottel decided to expand the book into a larger volume, Fiue hundred pointes, with the addition of hundreth good poyntes of huswifery. Harvey’s copy is a reprint from 1580, the year Tusser died.

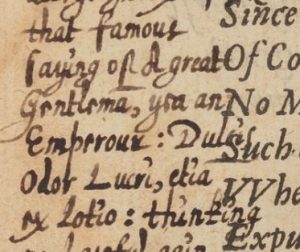

It stands out in Harvey’s library because of its subject, but also because of its genre: Fiue hundred pointes is a long poem that offers minute advice on how to live the pastoral life in accentual anapaestic, and predominantly in a-b-a-b rhyme. It’s a plain and sometimes grating style, but it is an easy meter to remember. Such rhymes were efficient instructional texts. Tusser’s farming manual was still being used as a teaching text in the eighteenth century, and some of its adages survive today: for example, “A fool and his money are soon parted” or “What a greater crime than loss of time.” Harvey gladly contributed in the margins of his copy quotations he picked up; for example, somewhere in the first pages he adds: “Dulcis odor lucre, etiam ex lotio” (“Profit smells sweet, even from urine”).

Harvey’s marginalia don’t mention Tusser’s stylistic or literal qualities. But in some of his first few annotations, Harvey does give this book a place in his library. He draws parallels between Tusser and the works of Xenophon, Hesiod and Virgil before recommending Fiue hundreth pointes as both useful for the economist and pleasant for the philosopher. Throughout his marginalia he refers to the classics, and continues to reference points of specific economic and political interest. Harvey’s marginalia make Tusser’s book seem less outlandish in the corpus.

Harvey may not expand on Tusser’s rhyme, but his relationship with verse is well known. “Harvey is not unknown to the lover of poetry . . .” so begins the lemma in a nineteenth-century literary dictionary, “he is the Hobynol whose poem is prefixed to the Faery Queen, who introduced Spenser to Sir Philip Sidney: and, besides his intimacy with the literary characters of his times, he was a Doctor of Laws, an erudite scholar, and distinguished as a poet.”

Harvey’s poetry in Latin shows his love of wordplay, puns, and ironic wit. It is showcased in his Gratulationum Valdinensium (1578), a series of poems dedicated to Elizabeth I. But, as one contemporary succinctly put it, Harvey was “more potent in his venom than in his honey.” His vitriolic pen worked considerably better than his other pens, as illustrated in his Three proper and familiar letters (1580). His love for the classical dactylic hexameter made his verse look and sound like that of a poetaster: dogmatic and a little awkward. How different was his approach to English verse! His unpublished experiments with English hexameters show a much more flexible approach: “to reform our English verse and to beautify the same with brave devices . . . lie hid in shameful obscurity,” he wrote to Spenser.

Others were less infatuated with Harvey’s verse: “He introduced hexameter verses into our language and pompously laid claim to an invention which, designed for the reformation of English verse, was practiced till it was found sufficiently ridiculous. His style was infected with his pedantic taste; and the hard outline of his satirical humour betrays the scholastic cynic, not the airy and fluent wit.” Even in 2016 that reputation persists. Edmund Gosse’s essay on Thomas Nashe accepts for truth Nashe’s accusations: “Gabriel Harvey is a personage who fills an odious place in the literary history of the last years of Elizabeth . . . wholly without taste, and he concentrated into vinegar a temper which must always have had a tendency to be sour.”

Only a very select group of Elizabethan poets risked trying their hand at imitating the classical meter in the vernacular. Harvey’s fellow experimenters—Spenser, Ascham, Sidney, and Thomas Watson—conversed at large about the rules for an English hexameter system, but Harvey was less enthusiastic. He refused to comply with rules and committed only to the idea that the length of a syllable in verse should correspond to its actual pronunciation. But he did not divulge how English sounds were to be measured.

Instead, Harvey seems to have leant towards the applied rules of classical Latin. In letters to his fellow experimenters he compares the idea of rules for verse to an applied custom and “natural” law. Here spoke Harvey the lawyer. He realized the potential of the vernacular to rival, and break free from, the “absolutist” rules of Greek and Latin verse. He maintained his relaxed approach to English hexameter. To create a natural, quantified verse in English, he “dare give no Precepts, nor set downe any Certaine General Arte.”

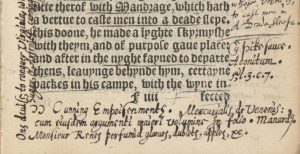

Harvey may not have filled the margins of Fiue hundreth pointes with remarks on its style and verse, but he was always attracted to the stylistic aspects of the texts he read. The AoR-team has spent a long time on a marginal annotation in Harvey’s copy of Frontinus’ Strategemes of warre (1539), that serves as a showcase of Harvey’s wit and love of puns (many thanks to Arnoud Visser for helping us out!).

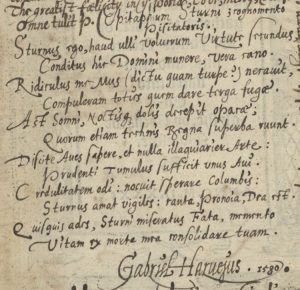

It is the epitaph of a sturnus, a starling. At the same time it is a warning to those to whom trust and hope come easily: “nocuit sperare columbis” is translated liberally as “Hopeful pigeons get hurt”! In a book about cunning war stratagems, this annotation is not out of place, but it is clearly very carefully crafted. It is also not so straightforward. The Latin is a little off and unlike Harvey’s usual language. It is bursting with puns and obscure references, and therefore a prime example of the horrors of translating a proud humanist’s Latin. The first line, for example, “Sturnus ego, haud ulli volucrum Virtute secundus,” is a play on “Turnus ego, haud ulli veterum virtute secundus,” a line from a speech by Aeneas’s greatest enemy, Turnus, given to him by Virgil in book XI of the Aeneid. Other seemingly odd phrases are yet to be traced back to the sources Harvey used for inspiration.

The Sturnus epitaph shows how Harvey approached language: with craftsmanship. He says as much in his correspondence with his fellow experimenters with the English hexameter. Literary and lyrical endeavor for Harvey is a craft rather than an art or a “pastime for educated gentlemen”; the writer is an artisan, a “smith of words,” rather than an artist. For Harvey, in the end, writing is as much a craft as working the fields.