Poets, popes, and polemics; or, methods for dating marginalia

One of the more fascinating aspects of working with the tangle of marginalia found in Domenichi’s Facetie, motti, et burle is the constant reminder that Harvey returned to and annotated the same book over a long period of time (1580–1608). Apart from clear visible differences in the quality of the handwriting and ink, there are other clues that help to date certain notes.

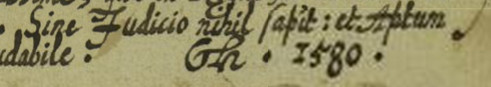

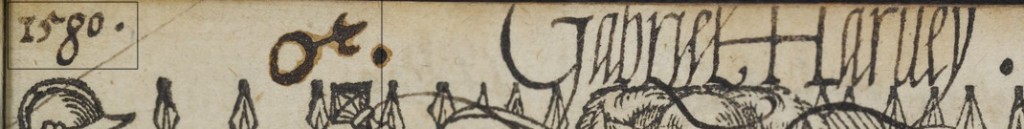

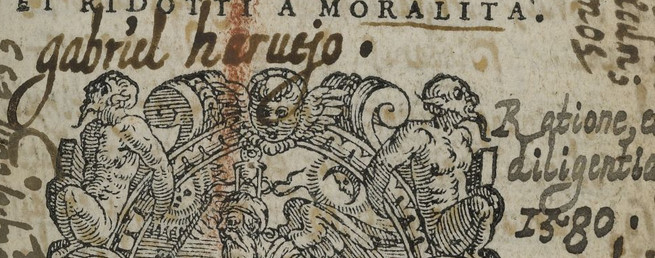

For instance, one might simply find the year written on the page, usually indicating when Harvey bought or finished the book. In the books that we are working with at the moment, several contain the date 1580:

Beyond this rather simple recording of the year, there are other methods for narrowing down the period of various marginalia. Since our job as transcribers requires tagging the names of people or books that we come across, I frequently end up digging through online catalogues trying to make sense of obscure names and book titles. As a result, I often find publication dates, which help determine a terminus post quem for particular comments.

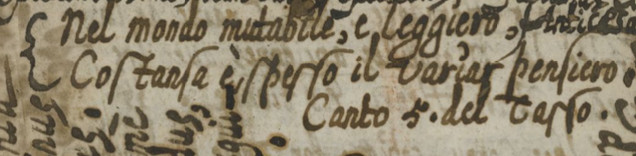

For example, on a blank page found at the end of the Domenichi text — in reality, facing the page of the Guiccardini text marked 1580 —, Harvey twice quotes the epic poem Gerusalemme Liberata by Torquato Tasso.

This poem was first published in its entirety in Italy in 1581, providing us with a rather solid chronological anchor. And given the uniformity between these notes and the surrounding annotations, it seems likely that the entire page was written by Harvey at the same time.

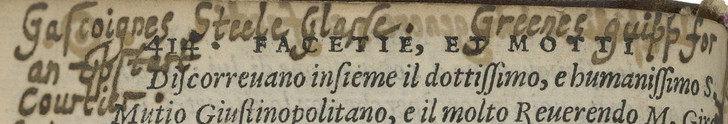

Using a similar approach to dating the various books referenced by Harvey, it becomes immediately clear that he returned to this same text with pen in hand much later than 1580–81. Earlier in the Domenchi, we find the following written in the head margin of a page:

And then further down:

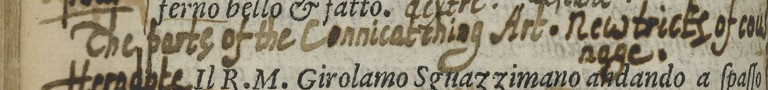

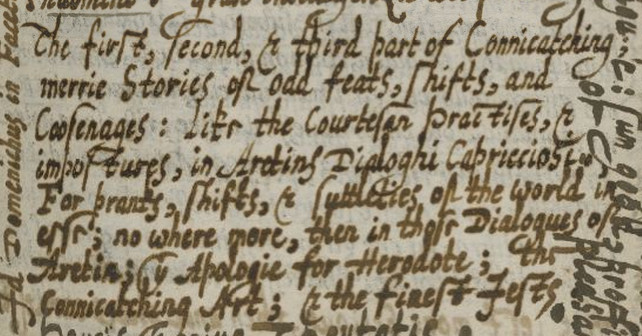

Much like the vast majority of marginalia in this book, these comments have nothing to do with the printed text. Instead, both of these notes point to Robert Greene, a writer with whom Harvey quarreled in 1592 following the publication of the former’s Quip for an Upstart Courtier. That book, which contained an attack on the Harvey family, appeared in print for the first time in 1592, leading to Harvey himself publishing a response later that year, Four Letters and Certain Sonnets. The references to “Cousenage” and “Connicatching” allude to a series of pamphlets written by Greene between 1591 and 1592.

The other work mentioned, George Gascoigne’s The Steel Glas, was published in 1576 – which doesn’t really help us make sense of the chronology. But if we look at Harvey’s Four Letters, we find that Gascoigne is mentioned several times when Harvey begins belittling Greene:

“I once bemoaned the decayed and blasted estate of Master Gascoigne, who wanted not some commendable parts of conceit and endeavour, but unhappy Master Gascoigne, how lordly happy in comparison of most unhappy Master Greene?”

One wonders whether Harvey was making notes of the polemic as it was going on. Is he simply responding to contemporary events? Is he preparing remarks for his own publications? Unfortunately, any hypothesis immediately becomes much more complicated when we move across the head margin to a note on the facing page, also written with a very similar quality of ink and writing instrument.

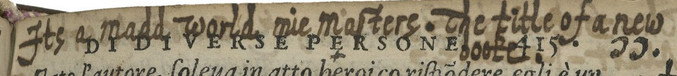

This “new book” is Thomas Middleton’s play A Mad World, My Masters, first printed in 1608. Clearly these notes could not have been written earlier, but what does this date mean for the references to Greene? Or is the title of Middleton’s play an anomaly?

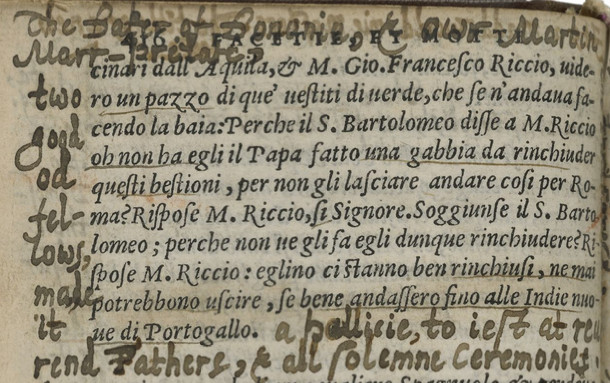

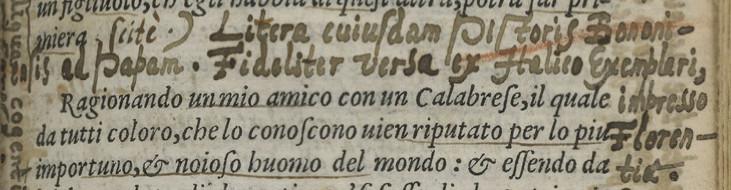

Moving forward, on the next page we find Harvey commenting about a peculiar open letter written to the pope by an anonymous Bolognese baker, and still with the same quality of handwriting and ink that appears on the previous page:

And on the facing page:

This second marginal note is actually a verbatim transcription of the title page of a book printed only once in Latin in England in 1607, meaning that, as with the references to Tasso, we have a stable chronological anchor. Yet now, within the space of four pages, we find references to a polemic from 1592 and two books printed for the first time in 1607 and 1608.

I’ll end with one more perplexing observation. Several pages after the reference to Greene’s polemical “Upstart Courtier,” Harvey again mentions his rival’s pamphlets on the art of “Conny-Catching.” Yet he seems anything but upset with his former adversary. In fact, he puts Greene on the same level as one of his other favorite writers of courtly life and merry-making, Pietro Aretino.

It’s unclear exactly how these things all fit together, and I am happy to leave the question to much more knowledgeable and perceptive scholars.