Sensation in the margins

Here’s the first blog post of our great new research assistant, Kristof Smeyers! Since arriving at CELL, Kristof has been working on Frontinus’ Strategemes and the latest addition to the AOR corpus, Tusser’s Fiue hundred pointes of good husbandrie, which has been recently acquired by Princeton University Libraries. Steve Ferguson, one of the driving forces behind AoR, has been so kind to supply us with high-res digital images of this great book, which for several decades has been part of a private collection.

Kristof’s blog heralds a period of more regular updates on the AOR site, including more in-depth information on the bookwheel viewer we have been working on, so stay tuned!

—

Historians have always had a knack for comparing their work ethos with that of other disciplines. Often it would be the wider world’s forcing these comparisons on them, but just as often they themselves would reach for far-fetched metaphors to mold their scholarly selves. Especially since the second half of the nineteenth century, when history professionalized, they have compared themselves (or are compared) to a variety of personae: historians are treasure hunters, miners, detectives, judges, but also gardeners, janitors, or even taxidermists.

But an older, seemingly more natural and spontaneous comparison is the one between history and archaeology. Historians and archaeologists have always been considered scientific siblings. And it’s that family I am now part of. My name is Kristof Smeyers and I’m a cultural historian, and since March one of the archaeologists of early modern reading.

This is not the first historian’s mask I have worn. A few years ago, I was a miner in the underground tunnels of the Bodleian Library in Oxford, delving for fossilized treasure: seventeenth-century star maps, early nineteenth-century political caricatures and pamphlets, tiny anatomical sketches, and massive books of old English cartography. Deep underground, I realized for the first time that books are not just carriers of text (and context), but also objects. Books are history of course; but books shape history too, and have a history of their own.

Archaeologists work with objects. With such materiality comes a sensation. Objects can radiate, have an attraction. The books I have been working on in the AOR project so far, Gabriel Harvey’s annotated copies of Frontinus’s Strategems of warre and Thomas Tusser’s Pointes of good husbandrie, though not physically gathering dust on my desk, reveal themselves to me foremost as material (and visual) objects and intrigue me. The Dutch historian J. Huizinga coined the term “historical sensation” for exactly such an experience: a “direct” link with a past and, implicitly linked to that directness, with an authentic, unvarnished truth.

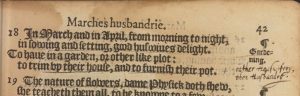

Harvey’s annotations are sensational because they not only reveal reading practices but also show a man interested in both the daily and the sublime. His light annotations in Tusser’s month-by-month manual for the ideal farmer consist mostly of surreptitious underlinings and marginalia that paraphrase such examples of farmer’s wisdom as “What a greater crime, than loss of time” or “‘Sweet April showers do bring May flowers.” Occasionally, when Tusser expands on another husbandly duty, such as tending to the herbs in the garden, Harvey underlines and objects: “rather Houswifery, then Husbandry.”

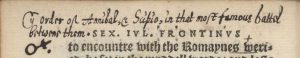

Ideas of manliness are more explicitly annotated throughout Frontinus, in which Harvey draws his Mars symbol for war and violence frequently. Here it’s the sublime that captures Harvey’s attention, the beauty and the brutality of war and strategy.

These marginalia objectify the book and open a portal to history: the handwritten references to the classics, the pedantic corrections Harvey added to the printed text (commas, hyphens, apostrophes, and missing words), the way in which he underlined with the same vigor the clubbing of cowardly soldiers (“souldiours crienge”) by Marcus Cato and the clubbing of moles in the garden—for the historian, these annotations are sensational because, for a moment, they cut through the crust of time. They can do so because of their anecdotic nature.

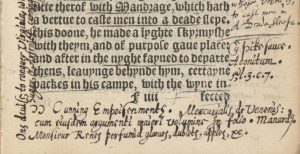

But the Archaeology of Reading project aims to systematically illustrate an early modern culture of reading. In this case the historical sensation can prove to be more of a hindrance than a stimulus. The temptation to delve into the context rather than focus on the transcription can be very persuasive. The sensations of history can tug rather hard at my sleeve. When Harvey mentions a mysterious “Monsieur René” underneath the words “caste men into a deade sleepe” and “wine infected” in the Strategems, I give in and soon find myself in the company of Renato Bianco, the perfumer of Catherine de’ Medici who set up an apothecary in the shadow of the Notre Dame. Also known as René le Florentin, “maître gantier parfumeur,” he introduced a fashion for perfumed gloves to Paris. But his successful career was haunted by rumors. Stories of secret passageways into Catherine’s bedchambers, of a shady laboratory in the back of his apothecary, even of murder, and . . . of the poisoned gloves of the Queen of Navarre.

Harvey’s marginalia are a sprawling, captivating world of references, cross-references, and associations. His library is a habitat of intellectual and material culture. One can browse through his annotations and get lost in time. But historians are not only archaeologists, they must also be curators. That’s why the corpus of the project is a choice: a selection from Harvey’s library, and soon a similar selection from the library of John Dee. Such a systematic approach is a necessity, but it is one I have to remind myself of quite regularly in order to avoid what Huizinga called “the drunkenness of the moment”—a profound intimacy between object and subject that takes you to a place where the sensation of a historical object overwhelms you.

What transcribing Harvey has made me realize, is that such a direct link with the past that allows us to touch history, in the end, doesn’t have to be physical. The AOR bookwheel shows that the marginalia have a strong material—and sensational!—value even when digitized.

It’s that tension between material and digital culture, but also between archaeological method and historical sensation, that makes transcribing Harvey’s marginalia so exciting for me.

One thought on “Sensation in the margins”