Some notes on translating Harvey

Happy 2016 from the Archaeology of Reading! This week we are getting back into the swing of things, and to celebrate the new year I thought I’d write another short post about the challenging (though fun) world of translating Harvey’s marginalia. Today, we’re going to look at two terms that I’ve run across several times in the Domenichi text but that also appear elsewhere in the AOR corpus: the Greek term “διότι” and the English “descant.”

1. διότι

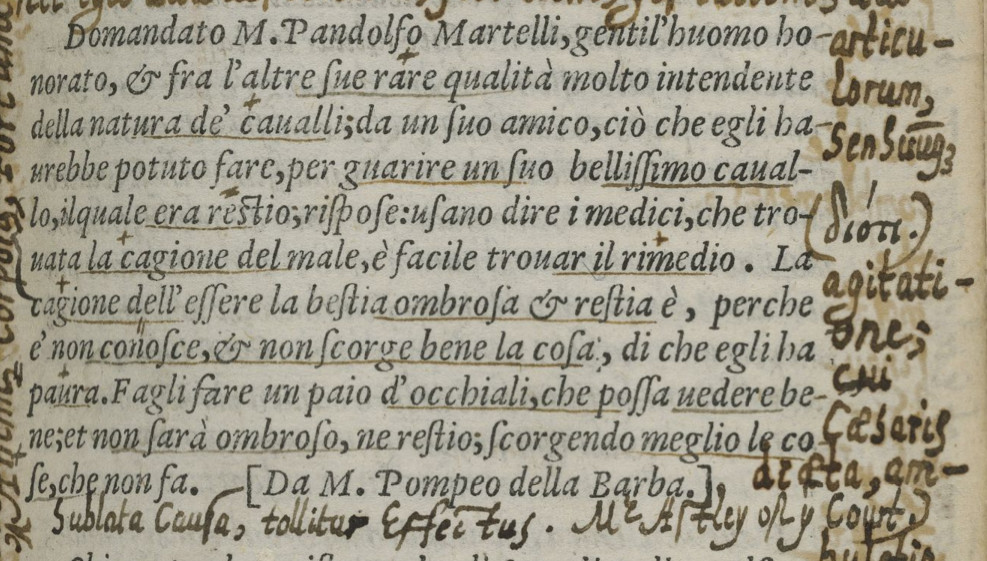

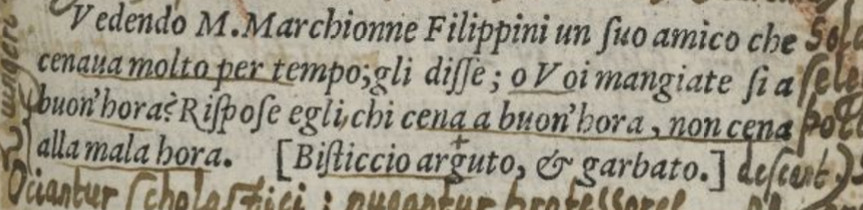

This Greek term generally means something like “for the reason that” or “because.” It would not normally cause any problems, except for the fact that occasionally Harvey writes the word, alone, in unexpected places. For instance, in the right margin of the following passage, bracketed by a longer note:

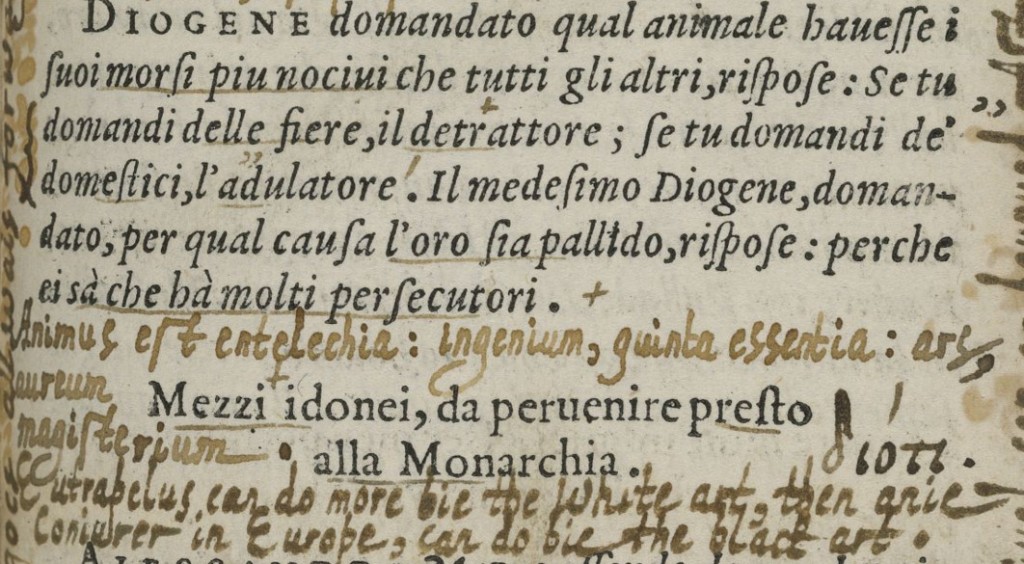

Or here, following a passage:

Translating this marginal note as “because” didn’t seem to make much sense to me. Thankfully, a while back I was chatting with Professor Grafton, who informed me of the philosophical usage of this term, specifically in Aristotle; διότι appears frequently throughout the Aristotelian corpus as a specific kind of analysis, when someone investigating the nature of things comes to understand “the reason why” (διότι) a particular thing is the way that it is. In other words, an argument can be described as διότι if it provides an explanation for some phenomenon. (If you’d like to learn more, the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy has a good introduction to Aristotle’s method of analysis.)

Given Harvey’s education and training as a lawyer, his usage of these technical terms is unsurprising. If we look back at the first image, the word appears next to the lines where we find a specific phrase, both underlined and marked with a plus sign: “usano dire i medici, che trovata la cagione del male, è facile trovar il rimedio” (doctors are used to saying that, once the reason for pain is found, it is easy to find the remedy).

In the second example we find a similar reference to the cause or reason for something. The Italian text (once more containing underlines and a plus sign) reads: “Diogene, domandato, per qual causa l’oro sia pallido, rispose: perché ei sa che ha molti persecutori” (Diogenes, when asked the reason for which gold is pale, responded: “Because it knows it has many persecutors”).

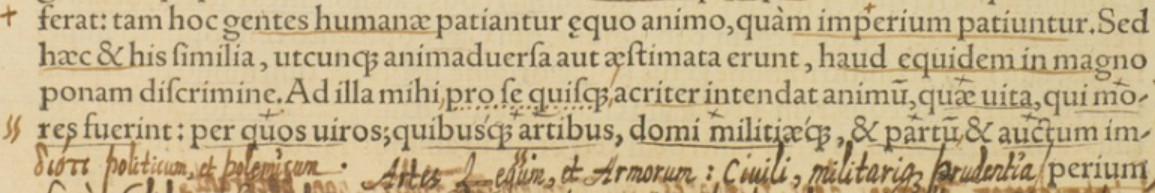

In both cases, Harvey seems interested in the specific sort of knowledge being demonstrated through these phrases. A third case may shed further light on his interest in this phrase (though it probably won’t provide us with enough information to exclaim “διότι!”) At the beginning of his massively annotated Livy, we find the word hiding down at the bottom, following the author’s prefatory note in which he explains the genesis of his history of Rome.

In this instance, the word is qualified with “politicum, et polemicum” (political and martial). As διότι seems like it’s being used as a substantive, the meaning of the phrase is probably something like “the political and martial reasons why.” If we look at the text directly above this annotation, we find that Livy is asking his readers to attend to certain aspects of Roman history: “The subjects to which I would ask each of my readers to devote his earnest attention are these—the life and morals of the community; the men and the qualities by which through domestic policy and foreign war dominion was won and extended” (translation by Benjamin Oliver Foster, online Loeb edition).

“The subjects to which I would ask each of my readers to devote his earnest attention are these-the life and morals of the community; the men and the qualities by which through domestic policy and foreign war dominion was won and extended” (translation by Benjamin Oliver Foster, online Loeb edition).

It seems to me like Harvey is making a distinction concerning the sort of knowledge that Livy is offering in his history. The work will offer a “reason why” for the founding of the city of Rome and its subsequent development.

2. descant

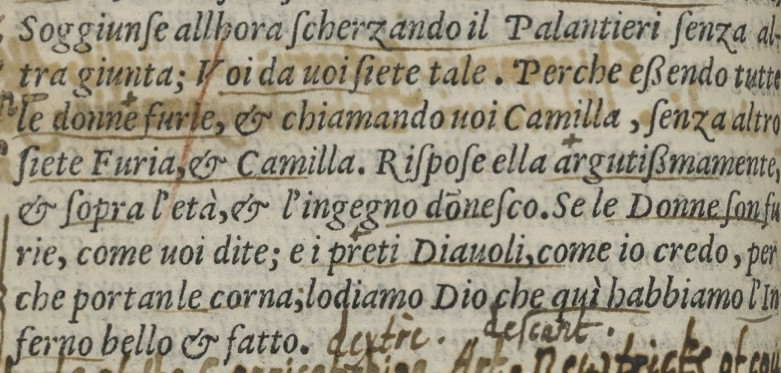

This word initially gave me some trouble, and I found it several times throughout the Domenichi text:

The form looks Latin, though if this were the case, it wouldn’t make much sense sitting on its own. After some time scratching my head, I realized that it’s an English term used primarily in the realm of music. The first definition provided by the OED reads: “The technique of writing or improvising music in parts, originally according to fixed rules in note-against-note style. Later more generally: the addition of a melodious accompaniment to an existing melody or harmonized tune.”

“The technique of writing or improvising music in parts, originally according to fixed rules in note-against-note style. Later more generally: the addition of a melodious accompaniment to an existing melody or harmonized tune.”

In this semantic domain, we can find an example in Shakespeare’s Two Gentlemen of Verona, in a witty exchange between Lucetta and Julia: “You are too flat / And mar the concord with too harsh a descant.”

The word also has a more figurative usage when referring to someone’s ability to discourse at length on a subject. However Harvey seems to be using a combination of the two; that is, his “descant” appears to refer to a sort of witty improvisation on a given subject matter. In both of the cases above, someone receives an insult before turning the phrase back on their interlocutor.

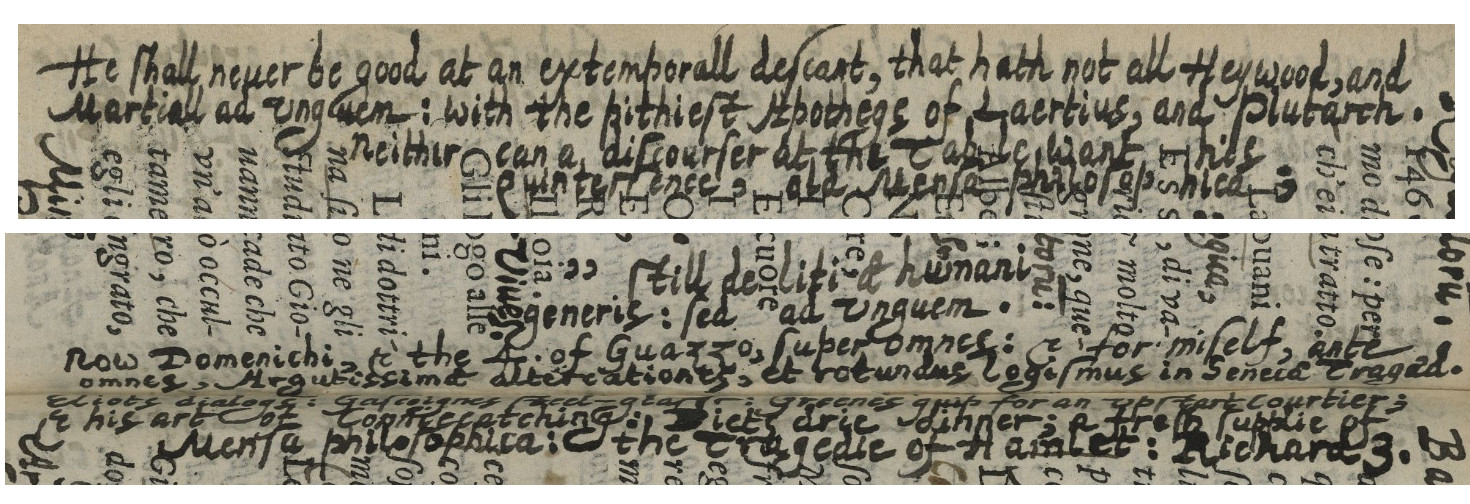

These moments of quick wit under pressure seem particularly interesting to Harvey, and indeed the word “descant” appears elsewhere as a quality desirable in the ideal courtier. In a long annotation moving across two pages (and perpendicular to the text!) we find:

Harvey starts off by saying, “He shall never be good at an extemporall descant, that hath not all Heywood, and Martial ad unguem.” The Latin phrase literally means “to the fingernail,” though translates into something like “by heart.” Thus the ideal courtier should memorize the epigrams of John Heywood and Martial first and foremost; after that, the pithy aphorisms of Diogenes Laertius and Plutarch; then, a book known as the Mensa Philosophica, an early modern work which has a collection of jokes suitable for the dinner table; finally, two Italian texts, the current book (Domenichi’s) and the fourth section of Stefano Guazzo‘s The civil conversation, a book of manners which also has a large collection of jokes. As a kind of addendum, Harvey also mentions the “most clever exchanges and rounded logic of Seneca’s Tragedies.”

I’m not sure that memorizing these works today would provide the same sort of urbane wit that Harvey was looking for. It certainly is an interesting list though.