Swedes, Lawyers, and Pi

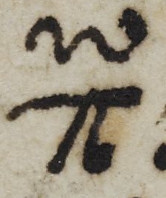

Today I’d like to look at one of the especially tricky problems in transcribing Harvey, a symbol that has appeared twice so far in our corpus. It looks something like the letter Greek pi with a wavy line above it.

The first text that contains this symbol is Thomas Freigius‘ Paratitla seu synopsis pandectarum iuris civilis (printed 1583), a summary of the Digest (also known as the Pandects), a 6th century compendium of Roman law that became the foundation for developing legal systems throughout Europe in the early modern period.

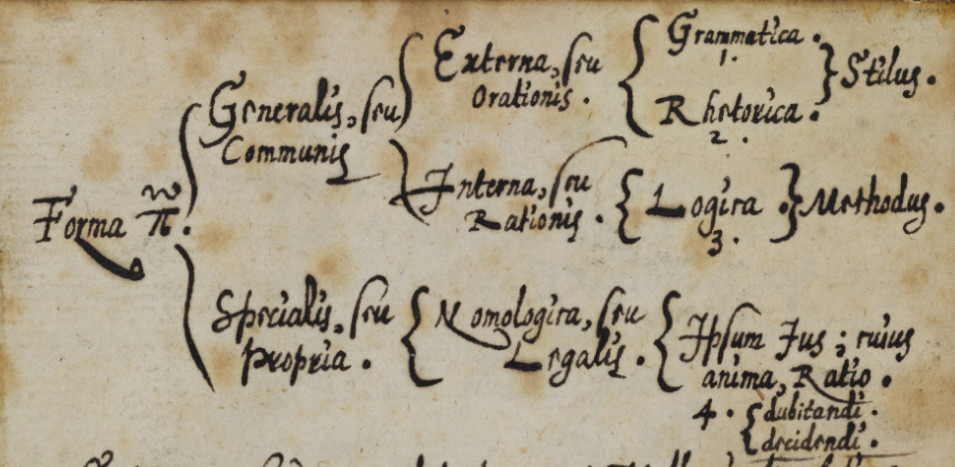

This chart, with the pi symbol on the left side, appears on a blank page before the text proper begins. It appears to be a graphical representation of the division of the Pandects according to Freigius’s own summary. Perhaps the symbol is an abbreviation for the Pandects? Harvey was trained as a lawyer, but would he have used this symbol? With just this single example, it is difficult to come to any conclusion, but if we analyze the other example, we can begin to formulate a more substantial hypothesis.

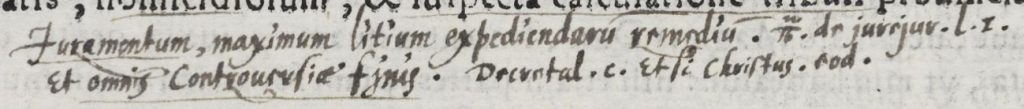

The second instance appears in Olaus Magnus‘ Historia de gentibus septentrionalibus (signed 1578 by Harvey). The work deals with the history and traditions of the Swedish people, a rather fascinating topic for Europeans at the time. In a section dealing with the legal customs of Sweden, Olaus describes the fact that many legal cases were addressed on the basis of swearing and upholding oaths. Harvey leaves the following marginal note:

Transcribed, this annotation reads:

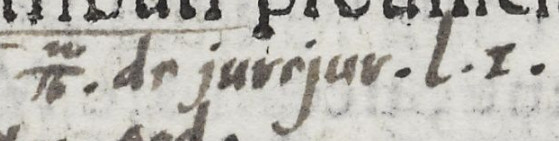

Juramentum, maximum litium expediendarum remedium. π.de jurejur.l.1.

Et omnis Controuersiae finis. Decretal.c. Etsi Christus. eod.

The annotation immediately presents some problems for translation, especially with the abbreviations which clearly reference other works. But, ignoring those abbreviations for now, these lines translate roughly to:

An oath is the greatest help in expediting lawsuits. [π. de jurejur. l. 1]

And it is the end of every dispute. Decretal. [c.] “And so Christ.” [eod.]

Due to my ignorance of early modern law, my first approach to making sense of this note was rather banal: Google. But given Google’s massive efforts to digitize early modern books, a simple search can return some incredibly useful results. For example, searching for “iuramentum maximum litium expediendarum remedium” immediately gives us a work that provides a brief summary of all the sections (or titles) of both civil and canon law.

Here we have a 1562 edition of the Titulorum omnium iuris tam civilis, quam canonici expositiones, that is, explanations for all the titles of civil and canon law. This work was composed by the German humanist Sebastian Brant, perhaps more famous for his satire Ship of Fools.

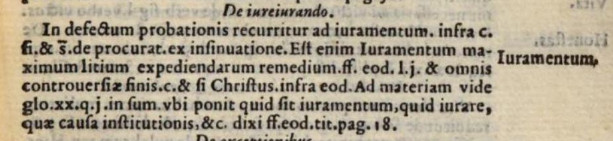

Using Brant’s legal compendium, however, I was able to figure out the various abbreviations in Harvey’s note, and ultimately confirm the meaning of the strange pi symbol. First, by searching through the volume, I found that one of the principal legal titles of civil and canon law turns out to be “De iureiurando” (“On swearing oaths”), which solves the problem of making sense of Harvey’s abbreviation “de jurejur.” The title can be found in multiple places, both in the Pandects as well as in the Decretalium (the Decretals of Gregory IX), solving as well Harvey’s abbreviation “Decretal.” In fact, in the relevant section of Brant’s discussion of the Decretalium, we find many phrases identical to the ones found in Harvey’s marginal note:

Leaving aside once more the citation abbreviations (ff.eod.l.j, c., infra eod.), there are three relevant portions of text that jump out because they also appear verbatim in Harvey’s marginal note:

Est enim Iuramentum maximum litium expediendarum remedium

omnis controversiae finis.

& si Christus.

Perhaps Harvey himself had a book such as Brant’s before him while he was annotating Olaus’ book on Swedish traditions!

If we leave behind Brant’s book and search for the title “De iureiurando” in the full texts of both the Pandects and the Decretalium (also found on Google Books), the abbreviations start to make even more sense.

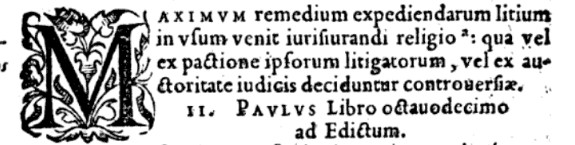

In the Pandects, Book 12, Title 2, “De jurejurando,” the first paragraph includes the phrase “Est enim Iuramentum maximum litium expediendarum remedium.”

Thus the first line of this title is the phrase that both Harvey and Brant extract and cite as “l.1.”

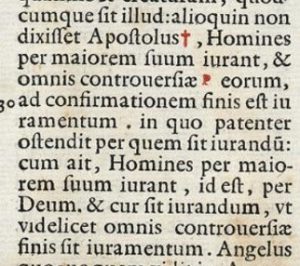

Likewise in the Decretalium, in Book 2, Title 24, “De iureiurando” we find that chapter 26 contains the text “Homines per maiorem suum iurant, & omnis controversiae eorum, ad confirmationem finis est iuramentum.”

In reality, this passage appears in a chapter (also known as a caput) that begins “Et si Christus,” which helps us make sense of the citation “c. Et si Christus.” It is clearly a way of helping a reader find a certain section by referring to the opening words.

In order to verify this method of abbreviation, I also looked around for information on early modern legal citation strategies. I managed to find a handy reference guide from the Harvard school of law, which, among many other things, informs us about the following strategies in the early modern period:

The basic form of their citations employs the abbreviation ‘ff’ for the Digest (probably a corruption of a curiously made upper-case ‘D’)

To this is added an abbreviated form of the title, and, normally, the first word of the fragment, frequently preceded by ‘l.’, for lex.

Many of the early printed editions also give an alphabetical listing of the first word(s) of the leges (fragments) in each of the parts of the Corpus.

If the reference is to a fragment that is in the same title in which the reference occurs, eo. (for eodem titulo) will be substituted for the name of the title.

Thus, we are in a position to begin translating Brant’s abbreviations:

ff.eod.l.j

ff – the Digest/Pandects

eod. – in the same title under discussion [i.e. “De iureiurando”]

l.j – in the first fragment (where j is often used for the Roman numeral i)

Likewise, with the other phrase from the Decretalium:

c. & si Christus infra eod.

c. & si Christus – in the chapter (caput) beginning “Et si Christus”

infra eod. – later, in the same title [i.e. “De iureiurando”]

This exact same method of citation can be seen in Harvey, the only difference being that, while Brant’s compendium uses “ff” to refer to the Digest/Pandects, Harvey uses the pi symbol with the wavy line.

π.de jurejur. – in the Pandects, under the title “De iureiurando”

l.1. – fragment 1.

Decretal.c. Etsi Christus. eod. – Decretalium, in the chapter beginning “Etsi Christus,” under the same title [i.e. “De iureiurando”].

Given that we earlier hypothesized that Harvey was using this symbol to refer to the Pandects, we now have even more convincing evidence. We also have an interesting point of departure for thinking about the ways in which Harvey may have been reading a description of Swedish traditions and customs. But I’ll leave that for another time!