Harvey’s joke books

Greetings, I’m one of the transcribers working on Harvey’s annotations for the Archaeology of Reading project, and I’ll also be contributing to the blog as I go along. I thought I’d start with an introduction to the text that I’m currently working on: a single volume comprising two sixteenth-century Italian joke books bound together and currently residing in the Folger Library:

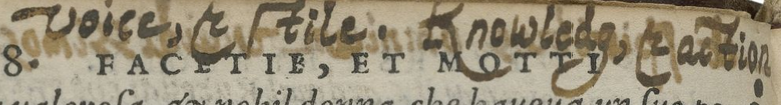

Domenichi, Lodovico. Facetie, motti, et burle di diversi signori et persone private (Venice, 1571)

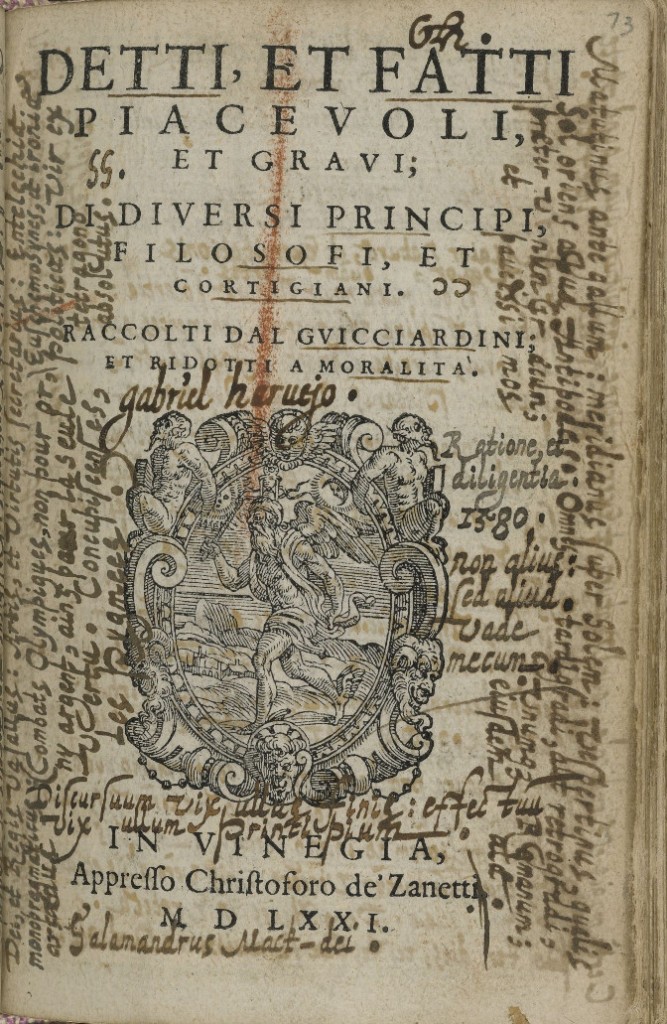

Guicciardini, Lodovico. Detti et fatti piacevoli et gravi (Venice, 1571)

A significant chunk of the Domenichi text is missing (the first 320 pages), but here’s the title page for the Guicciardini inserted right into the middle of the volume.

You can probably see why Harvey’s use of this book is so interesting: he seems to be completely allergic to blank space.

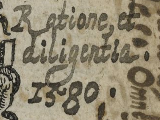

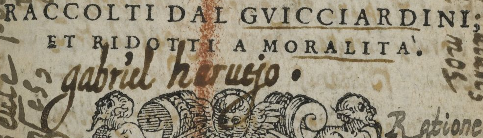

Even with just this title page, several interesting aspects of Harvey’s practice are noticeable. Differences in ink, position, and content within the annotations suggest that he came back to the book at several points and for different reasons. These layers provide some interesting clues to the way Harvey was making use of the book as an object. For instance, we see him dating and signing the page, a practice he follows in most of his other books:

He also underlines some of the text, as well as intervening to offer some orthographical corrections (note the semicolon after “Guicciardini”).

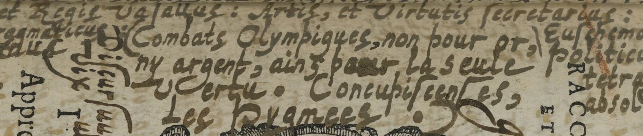

We also see Harvey’s use of different languages. Though the majority of marginalia on this page are in Latin, there is a smattering of French in the left margin:

The content of this margin is also a good example of the peculiar character of Harvey’s annotations: they don’t always seem to fit together in an immediately recognizable fashion. Here we see Harvey commenting on the qualities of the professional secretary in Latin, while in French he seems to be talking about the goal of Olympic combat, which ought to be virtue and not gold or silver. An immediate connection between these two annotations might be made through the reference to Vertu/Virtutis, but it’s always difficult to make sense of Harvey’s choice of content, language, and position within the book as a whole.

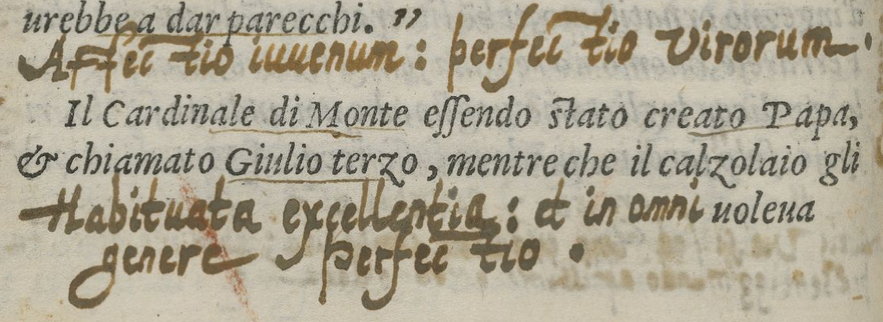

In reality, the majority of the marginalia throughout this volume rarely has to do with the printed text. Instead, Harvey seems to have used the blank space in these books to write a sort of manual or guide for the practical gentleman. “Manual” might be too strong a word, as there does not appear to be larger cohesive structure, but rather a vast sea of aphorisms, citations, and other remarks—all in various languages.

This is not to say that there aren’t any larger conceptual patterns, and in later posts, I’ll point out some of those recurring elements.

Yet, despite the overwhelming amount of material in the margins seemingly unrelated to the text, Harvey does actually respond to what he’s reading. For example, after a joke he might leave a note about his reaction.

The majority of these “responses” tend to follow the end of the story or joke and are typically in Italian or Latin.

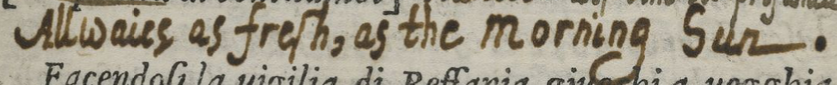

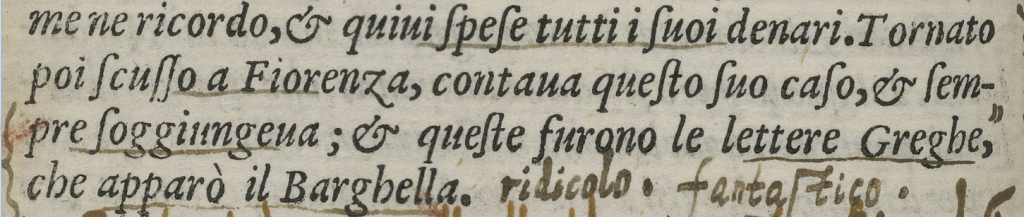

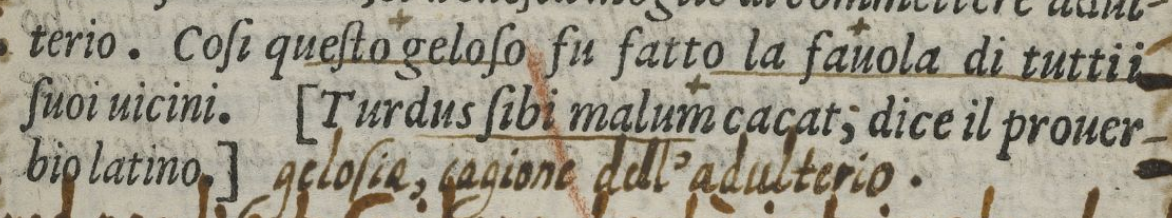

In rare moments, however, Harvey seems to have been particularly fond of a joke, and his response seems a bit more personal. I’ll end with a joke that pleased Harvey so much that he wrote a comment in English.

One day, while the Archbishop of Toledo was standing at his window, he heard a peasant repeatedly beating a donkey. Moved by compassion, the archbishop began to shout from the window, “Stop, stop, or you’ll kill him, you tactless peasant!” The peasant responded, “Forgive me, m’lord, I didn’t know my donkey had relatives at court.”

(It might be a bit tricky at first, but those are two s’s and an e!)

![[My Asse confuted.]](http://archaeologyofreading.wpshared.library.jhu.edu/wp-content/uploads/sites/21/2015/03/myasse.png)