Dee and his books

Summer or not, we are slaving away at the CELL office in order to transcribe all the annotations contained in the books which are part of our Dee corpus! This blog post, by Finn Schulze-Feldmann, one of the three research assistants involved in phase 2 of AOR, reflects on Dee’s different annotation styles.

—

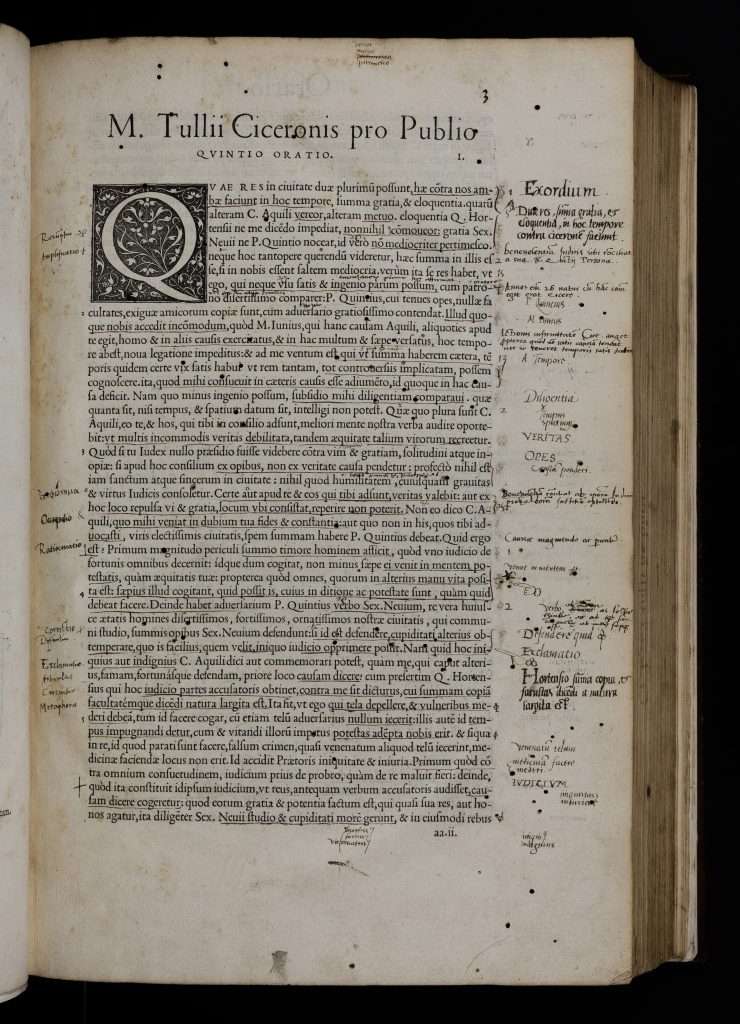

When transcribing John Dee’s marginal notes, one comes across many different styles of how to annotate a book. We all know some who consider books to be so sacred that their immaculacy shall not be tainted under any circumstances, and others who quite willingly leave their individual imprint on a book, scribbling their thoughts on the margin and highlighting passages in all the colours of the rainbow. If Dee had had different colour options available too, he would most certainly used them. His copy of Cicero’s Pro Publio Quinctio is at first sight slightly overwhelming to say the least. There are plenty of comments in the margins, heavy underscoring and various different drawings and symbols. Hardly any pages are left untouched. Thanks to these annotations we are able to gather some understanding of how a scholar as prolific as Dee worked.

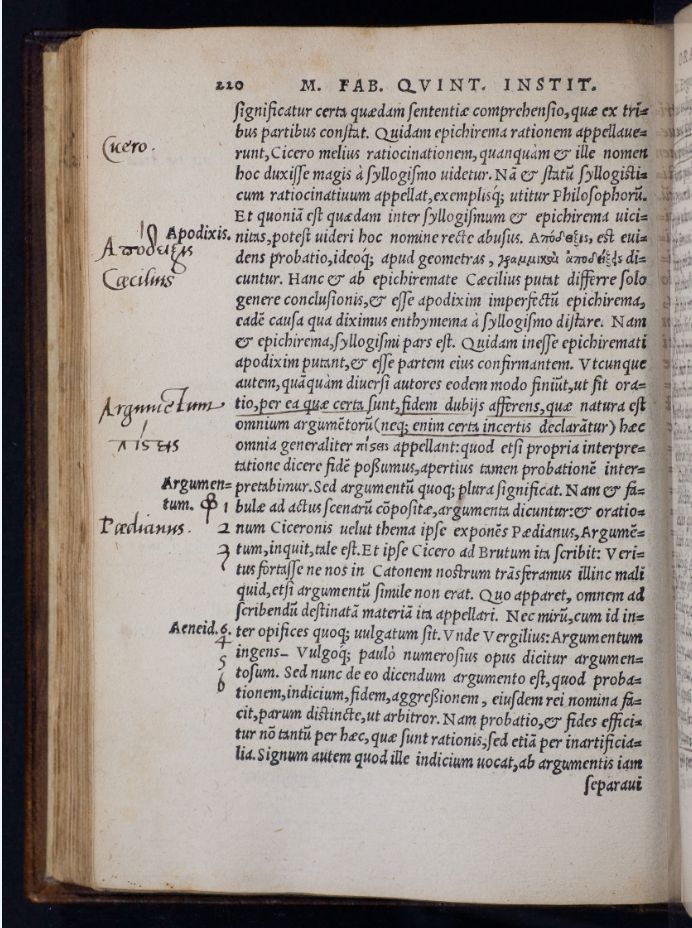

This is, of course, not to say that Dee subjected all his books to such excessive treatment. Quite the opposite! His copy of Quintilian’s Institutio oratoria could serve as an example in any modern-day handbook on how to read, highlight and annotate texts. Measured and never in a way that the reader could not grasp them immediately, the annotations are a guide through the text – and a delight for those transcribing them. They reference other works of Cicero, number lists mentioned in the text and provide brief summaries. Thus, to navigate through the text is made an easy task.

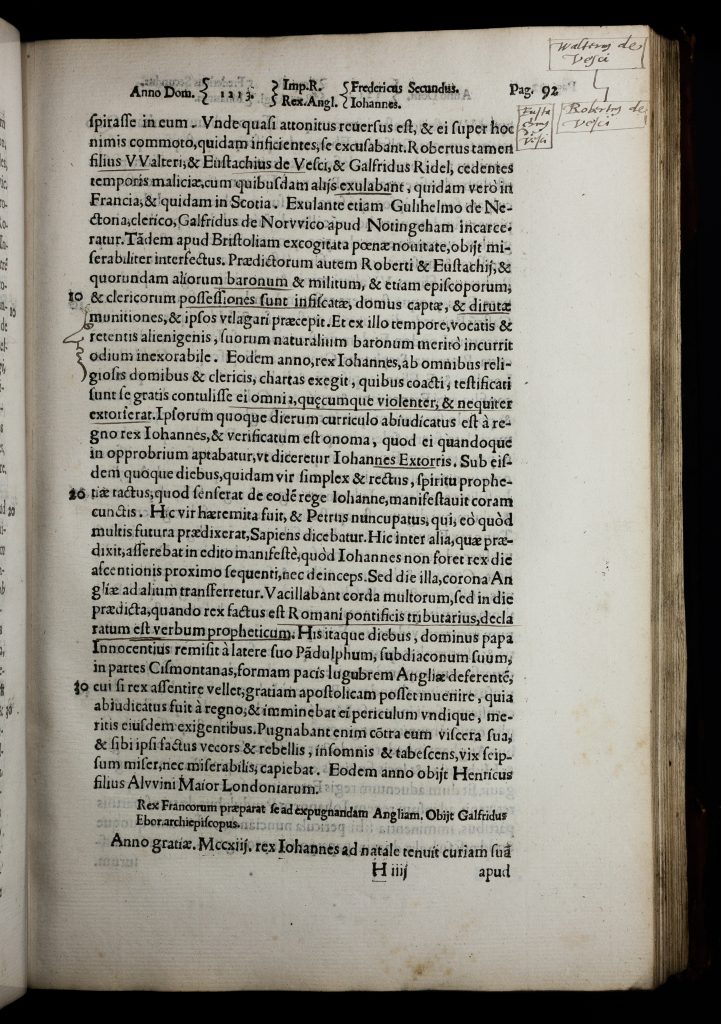

And then there is a third kind of annotations. Scattered through all his books, there are some that might be of interest not so much for their scholarly purposes, but rather they allows us to get closer to John Dee the person, or shall I say, the artist? Dee used not only to annotate books, but also to draw in books. Admittedly, the majority of his drawings mark names in genealogical trees as kings or queens. But there are also the odd ones that are a bit more playful. One of my personal favourites is a face that is seemingly randomly drawn in a margin of Dee’s copy of Matthew Paris’s Flores historiarum.

Their entertaining effect aside, the different ways in which Dee annotated his books do pose questions regarding their purpose and use. Would anyone but Dee be able to make sense of his densely annotated Cicero volumes? They seem to contain different layers of annotations. Those in a neat hand would still help a modern-day reader to find their way around the text. Others such as notes confirming or rejecting what is written and references to other works bear valuable insight in Dee’s intellectual engagement with the text. Especially the Cicero mentioned above appears to be a book he had read over and over again, each time with another focus. A rich repository for generations of researchers to come, none of Dee’s contemporary, I suspect, would have benefited much from these. As the printed text itself is at times even obscured by the marginalia, this volume seems dedicated to private study alone. In contrast, it would not be much of a surprise if the well-measured and neatly written notes in the Quintilian were indeed intended to be read by others. They are instructive and insightful. That Dee had allowed himself a little digression by drawing random faces and crowns, readers both today and in the past may smilingly excuse.