John Dee’s Astronomicon and the Thirty-Six Decans

This blog post is written by another research assistant, Matt Beros. Matt is currently working on the first volume of Cicero’s Opera after just having finished transcribing Quintilian’s Institutionum oratoriarum!

———

In this post I will be briefly looking at some of John Dee’s astrological marginalia in UCL’s copy of Firmicus Maternus’ Astronomicon Libri VIII (1533). Dee appears to have revisited this work several times judging by the evident variations in handwriting style and quality of ink. The frontispiece is inscribed: ‘Ioannes Deeus 1550. 22 Maij Lovanij’ but many of the annotations are in the italic hand typical of Dee’s later writing style. Dee’s reference to a ‘blasing star’ in the constellation of Cassiopeia in 1582 provides us with an approximate terminus ad quem for his later annotations. The majority of the marginalia are in Latin and English with the occasional term in Greek and in one case Biblical Hebrew.

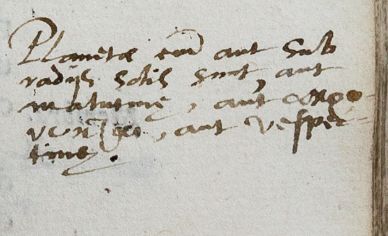

Many of the Greek astrological terms are difficult to identify since they often appear in the midst of a Latin marginal note. For example, in the following marginalia, the rather cryptic word following ‘solis sunt aut matutin[a]e, aut’ is the Greek astrological term: ‘ακρονυκτα’ (acronyctae).

‘Planeta[e] cu[m] aut sub radijs solis sunt, aut matutin[a]e, aut ακρονύκτα, aut vespertin[a]e.’

The planets as either under the rays of the sun, or as the morning star, or acronyctae, or as the evening star.

The term ακρονύκτα is a word from the Ptolemaic tradition referring to stars rising in the sunset. Numerous other astrological terms, such as κενοδρομία (kenodromia), literally ‘void of course’, occur in Dee’s marginal glosses throughout the Astronomicon. Porphyry of Tyre helpfully defines ‘kenodromia’ in his ‘Introduction to the Apotelesmatika of Ptolemy as when the moon is passing through a ‘void’ region in the zodiac.

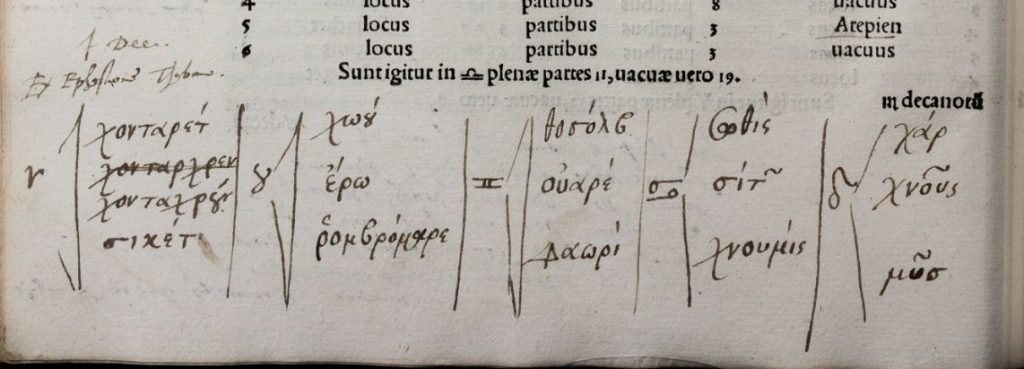

A more substantial example can be seen in Dee’s Greek annotations on the table of the thirty-six decans. The decans were Egyptian sidereal deities each associated with a zodiacal sign and closely related to the figure of Hermes Trismegistus. Maternus attributes this ‘most true and immutable theory’ to the Egyptian high priest Petosiris and the pharaoh Nechepso. In the margins of the text Dee scrupulously notes the equivalent Greek terms for each of the thirty-six decanal names listed in Maternus’ table. Beneath the table Dee writes, ‘J Dee. Ex Ephastione Thebano’ (from Hephaestion of Thebes). In another annotation Dee notes:

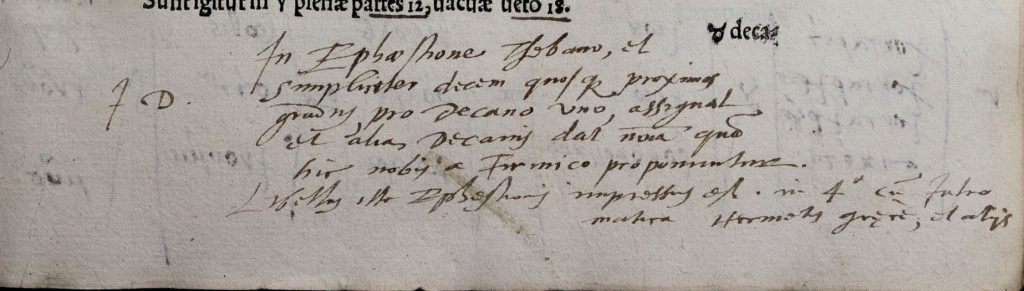

‘In Epha[e]stone Thebano, et simpliciter decem quosque proximos gradus, pro decano vno, assignat et alias decanis dat nomina quam hic nobis a Firmico proponuntur. Libellus ille Ephestionis impressus est. in 4˚ cu[m] Iatro matica Hermetis graere, et alijs’

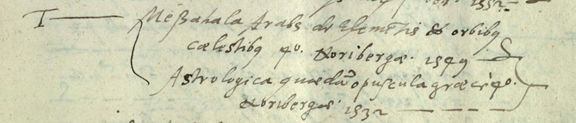

Clearly Dee is citing another work as his source for the thirty-six decanal names from Hephaestion of Thebes. On the basis of this marginal annotation we know that this work by Hephaestion of Thebes is a ‘libellus’ (a small book or tract) collected in an anthology of Greek Hermetica (Hermetis graece, et alijs). Dee does not provide the title of this collection or the title of the libellus nor any publication date. We do know that this book is in ‘4˚’ (quarto) format and includes the title of another work beginning with ‘Intro[…]’. The title of this latter work was not immediately recognizable either. On the basis of Dee’s handwritten catalogues we know that he arranged many of his books by format. The detailed citation suggests that this is possibly a book from Dee’s personal library. Whilst perusing Dee’s 1583 autograph catalogue under ‘libri in 4˚’, the following title caught my attention: Joachim Camerarius’ Astrologica. Qua[e]da[m] opuscula gra[e]re 4˚ Nori[m]bergae (1532).

Camerarius was a German classical scholar who published the first Greek edition of Ptolemy’s astrological text, Tetrabiblos in 1535. The Astrologica was a slightly earlier anthology of Hermetic astrological tracts in Greek with selected works translated in Latin. Dee’s own copy of the Astrologica is bound with the Arabic astrological work, Messsahala de elementis et orbibus coelestibus (1549) and currently housed at the Bodleian library, Oxford. Camerarius’ anthology collected Hephaesiton of Thebes’ Ἀποτελεσματικά, Vettius Valens’ Florilegium and the Ίατρομαθηματικά ascribed to Hermes Trismegistus. The final work, Ίατρομαθηματικά is Latinized as ‘Iatromathematica’. Now we are in a position to transcribe the second title listed in Dee’s marginal annotation as ‘Iatro[mathe]matica’. If we closely examine the Ἀποτελεσματικά (Apotelesmatika) of Hephaestion of Thebes, we can see that Dee appears to have written the decanal names verbatim including the precise same Greek contractions as the Camerarius edition. This is fairly compelling evidence that Dee had Camerarius’ anthology close at hand while he was annotating his copy of the Astronomicon. Dee also adds an additional column to Maternus’ table under the title ‘grad[us]’ (degree). Dee’s column is simply the cumulative sum of each preceding degree of separation between the decanal positions in the zodiac. In other words, it indicates the position of each decan in the zodiac for each sign between 1˚-30˚.

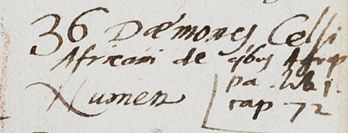

Two other interesting marginal notes cite additional sources for the decanal names. One marginal note references the thirty-six daemons of Celsus Africanus and another notes the thirty-six horoscopes in the Asclepius, a tract from the Corpus Hermeticum. Dee provides a detailed citation for Celsus Africanus’ discussion of the 36 daemons in Heinrich Cornelius Agrippa’s De Occulta Philosophia Libri Tres.

’36 Da[e]mones Celsi Africani de q[ui]bus Agrippa. lib[er] 1. cap. 73.’

36 demons of Celsus Africanus from which Agrippa cites in Book 1, Chapter 71.

Agrippa’s work had a notable influence on Dee, his September 1583 catalogue housed at the British library (Harley MS 1879) lists three different editions of De Occulta Philosophia (fols. 39, 44v , 53v). The Celsus Africanus passage in Agrippa describes the decanal names as referring to daemons which were believed to exercise an influence over corresponding parts of the body. Finally, Dee also cross-references another source of the thirty-six decans in the dialogue of Asclepius, a work that was enjoying renewed attention in the early modern period following Marsilio Ficino’s publication of the Corpus Hermeticum in 1471.

Maternus ascribes an ancient Pharonic origin for the thirty-six decanal names but the transmission of these terms through various Graeco-Egyptian sources is far from straightforward. As William Sherman points out, “Dee often pairs the terms ‘ancient’ and ‘credible’ but he also had an awareness that the older the information the greater the need for careful scholarship, particularly in terms of textual transmission.” Dee’s marginalia on the decanal names is an interesting example of his reading practice of comparing and collating different texts from his library. Such marginal notes attest to Dee’s philological interest in the Ptolemaic astrological tradition and his scholarly caution in comparing variant textual sources.