On neologisms and horses

Today I’d like to share one of the many complex—and often maddening—aspects of working with Harvey’s marginalia: his neologisms.

His annotations throughout the Domenichi text (which I shared in my last post) frequently contain technical words, mainly borrowed—or entirely invented retrospectively—from Greek. I say “technical” because these words seem to serve Harvey as a means of reducing a particular philosophical concept to a single term. For instance:

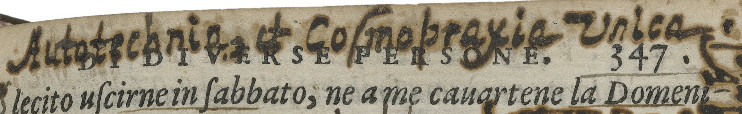

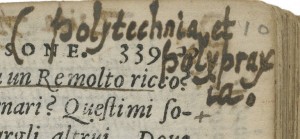

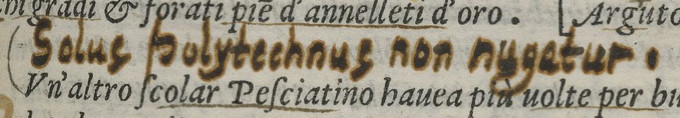

Autotechnia, Cosmopraxia, Polytechnia, Polyptaxia, Polytechnus.

Almost all of these specific examples exist in Ancient Greek literature, although they are quite rare (for example, take the entry for polytechnia in the Liddell & Scott Lexicon, which attests to only four uses in total). However, the component parts of these words are not particularly complicated, for instance: poly → ‘many’; technia → ‘skillfulness in an art.’ The problem comes from translating them into English, especially in the context of Harvey’s more compact aphorisms.

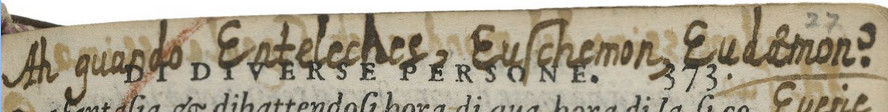

“Ah, when Enteleches, Euschemon, Eudaemon?” One might consider translating these terms as “actual, refined, blessed.” Anyone who knows a bit of Greek will probably immediately jump to correct me, “Yes, but it could also mean . . .”

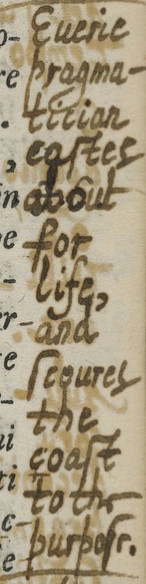

These terms are typically associated with the practical man. Indeed, immediately following this list of three characteristics Harvey writes, in English:

“Everie pragmatician castes about for life, and scoures the coast to the purpose.” This phrase serves as a reminder that the practical person must always be on the lookout for useful things (phrases, activities, models) that contribute to one leading a fuller life. The implication seems to be that success as a pragmatician might lead to becoming Enteleches, Euschemon, and Eudaemon.

A key term that returns frequently in conjunction with practical activity is, in fact, enteleches, which also appears in the more properly philosophical form of entelechia. This word might be familiar to anyone who has studied ancient philosophy, especially Aristotle, where entelechia means something like “actualization”—as in the actualization or realization of something that exists potentially. We could translate this term as “actualization” in Harvey’s marginalia, but things become a bit trickier once we see his other, more fanciful, uses:

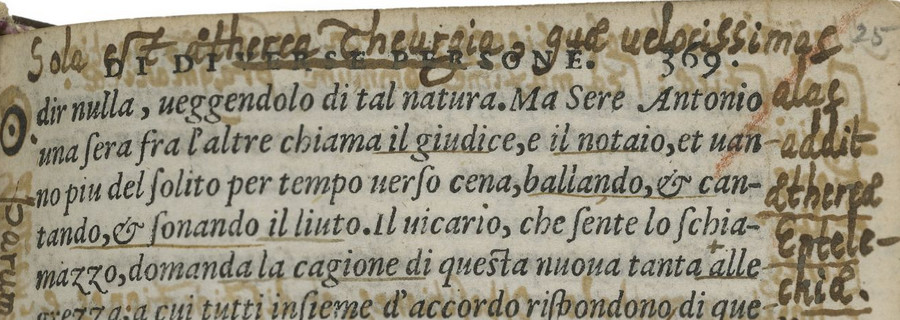

“Sola est aetherea Theurgia, quae velocissimas alas addit aethereae Entelechia.” → “Divine Theurgy alone is that which gives quickest wings to divine Entelechia.”

The meaning of this phrase is not immediately clear, which makes translating it into English rather challenging. And if Entelechia is a practical activity, what are we to make of this term Theurgia, which might be referring to magical ritual? How does “divine-working” fit with “practical actualization”?

One question you might be asking yourself: Does Harvey only use these peculiar terms in Latin? In almost all cases, the answer seems to be yes. However, I have come across one peculiar instance where Harvey’s technical vocabulary makes an appearance in Italian, when he is responding to a specific joke in the book itself. As we saw in my last post, Harvey’s responses to the text are almost always brief, and not particularly interesting. Occasionally, however, something seems to strike his fancy enough to evoke a comment.

Here’s a translation and transcription of this joke, which is rather offensive:

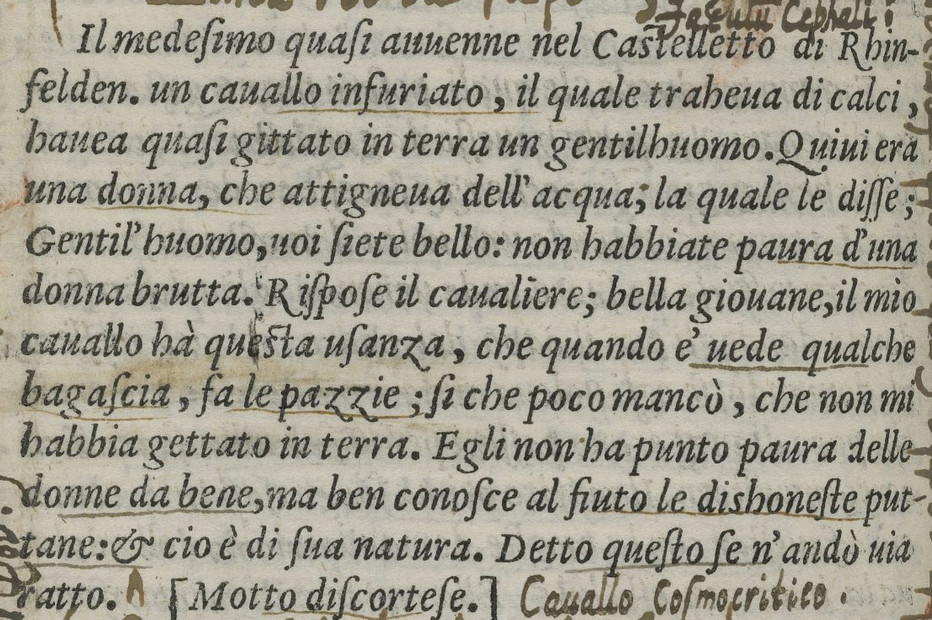

Un cavallo infuriatio, il quale traheva di calci, havea quasi gittato in terra un gentilhuomo. Quivi era una donna, che attigneva dell’acqua, la quale le disse; Gentil’huomo, voi siete bello: non habbiate paura d’una donna brutta. Rispose il cavaliere; Bella giovane, il mio cavallo ha questa usanza, che quando e’ vede qualche bagascia, fa le pazzie, si che poco mancò, che non mi habbia gettato in terra. Egli non ha punto paura delle donne da bene, ma ben conosce al fiuto le dishoneste puttane: & ciò è di sua natura. Detto questo se n’andò via ratto.

[An enraged horse was bucking and almost threw a gentleman to the ground. Nearby was a woman drawing some water, who said, “Good sir, you’re handsome, you shouldn’t fear an ugly woman.” The knight responded, “Fair young lady, my horse has this tendency, that when he sees a tramp he loses his mind, and here he almost threw me to the ground. He’s not at all afraid of decent women, but he has an excellent nose for recognizing dishonest harlots, and that is his nature.” Having said this, he left at once.]

The editor of the book remarks that the knight’s response is a motto discortese, that is, a merely “discourteous” quip. I suppose we can’t ask too much from 16th century editors. The interesting part is Harvey’s comment.

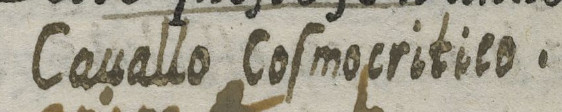

“Cosmo-critical horse.”

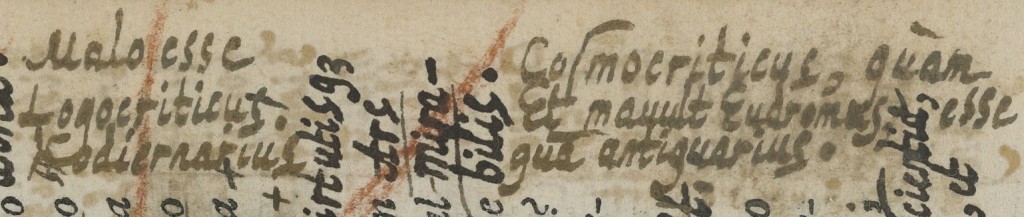

In reality, the word cosmocriticus is an invention of Harvey’s, and it means something like “a critic of the world.” Elsewhere in the book, we find Harvey setting up this idea in opposition to another term, logocriticus.

“I prefer to be a critic of the world than a critic of words.” Here Harvey is contrasting the man of action (i.e. the pragmatician) with the man of words. Strange that we should then find the embodiment of the critic of the world in the form of a horse.