Harvey reading verse

As mentioned earlier, the latest edition to the Harvey corpus is Thomas Tusser’s Fiue hundred pointes of good husbandrie (London, 1580), recently acquired by Princeton University Library. The book is different from the other books in the corpus in terms of its topic —husbandry, the management or political economy of the household— but also in its literary style. For, unlike the other books in the corpus, Tusser’s book is written in verse. This blog will assess whether or not this fact exerted any influence on Harvey’s reading strategies.

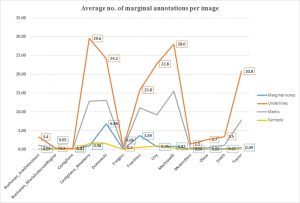

First, let us see whether a fairly straightforward statistical analysis reveals any divergent reading patterns by comparing Tusser’s book to the other books in the corpus. In the following graph I calculated the average number of marginal annotations (divided into the four main types: marginal notes, underline, mark, and symbol) per digital image.

The figures show that Harvey annotated Tusser’s book fairly heavily—it is the sixth most densely annotated book in the corpus. It seems, though, that nothing out of the ordinary was going on. Harvey didn’t use a particular type of annotation more often than in other books, for example. The only thing that caught my eye is the fairly (but not extremely) high average number of underscores. The underline tag captures every word or sequence of words of the printed text that is underlined (as long as a set of words is underscored uninterruptedly), as a result of which the average number of underscores can be “inflated” when a reader underscored a lot of single words. Moreover, although working with the average number of underlines per digital image reduces the possibility of generating misleading statistics as the result of books being different in length (i.e., the number of pages), the different size of the book can still distort the statistics (e.g., a page of the Livy contains more words, and hence possibly more underlines, than a book in octavo format). We therefore should not take the statistics at face value: they can be misleading, as they have been influenced by various factors, including the size of the book and our transcription practices.

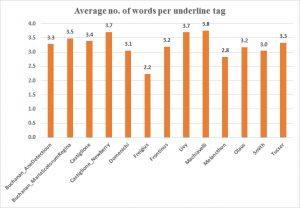

In the following graph we break down the number of instances of underscoring in the printed text further and show the average number of words per underline tag.

As the graph shows, Harvey seems to have been remarkably constant in his underscoring practices across the corpus. Whereas the total number of instances he underscored one or more words in the printed text varies greatly per book (from 48 in Buchanan’s Maria regina Scotorum to a whopping 26,088 in Livy’s History of Rome), the average number of words he captured by underscoring part of the printed text actually is quite similar (the only exception being Freigius’s Paratitla). These statistics thus seem to indicate that Harvey did not interact with the printed text of Tusser’s Husbandrie in a different way. Of course we could supplement this analysis with a more thorough linguistic scrutiny of the data, for example, focusing on the classes of words that are underscored. This falls outside the scope of this blog, so I just mention the possibility here.

We should complement our research with a more qualitative analysis of the AOR data set, though. In my opinion, statistics can be extremely useful in laying bare patterns that would have been difficult to discern with the more traditional scholarly methods usually associated with analog research environments. However, digital environments allow us to fruitfully combine quantitative and qualitative analyses. In this particular case, let us have a look at whether the marginal notes contain comments on, for example, the literary style of the book, or whether he frequently used particular symbols, such as Mercury, which Harvey used to mark passages in the printed text about eloquence (and also trickery).

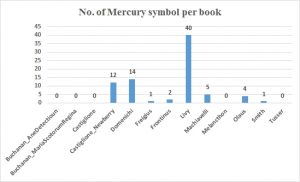

To start with the Mercury symbol, here’s an overview of the appearance of this symbol throughout the AOR corpus.

This path of inquiry clearly is a dead end, for the Mercury symbol does not appear once in Tusser’s Husbandrie. Moving on, neither did a simple search for “verse” yield a lot of results. In Tusser’s Husbandrie, Harvey did not mention this word in his marginal notes and only underscored the word “verse” twice: one time in the index at the end of the book, when referring to “Staints Barnards verses,” and the other time as part of the words “everie verse,” in the preface to the reader. In the other books in our corpus, Harvey did mention the word “verse.” For example, in Domenichi’s Facetei he wrote, “How many verses are there. A 100,” and in Guicciardini’s Fatti et detti, “Hos ergo versiculos feci: tulit alter honores” (I wrote these little verses, and another man received the honors). In Castiglione’s The Book of the Courtier, Harvey underscored “foolish in verses” in a sentence that describes the foolishness of some men in particular activities.

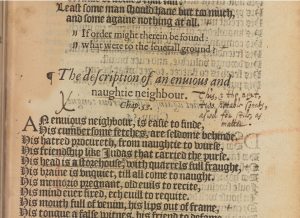

A search for style/stile yields more results. In Tusser’s Husbandrie, next to the header “The description of an enuious and naughtie neighbour,” Harvey wrote: “This, & the next, two notable sonets, aswel for stile, as matter.” (Interestingly, both sonnets are marked with red chalk, possibly another way of engaging with this book.)

When examining Harvey’s other marginal annotations in Tusser’s Husbandrie, it quickly becomes apparent that many of them were written in the upper margin and summarized the content of a page or section, the marginal notes basically functioning as headers. Moreover, the notes comment on the content of the printed text, not on its literary style.

Although we should take into account the facts that the data can be interrogated in many more ways and that our corpus is limited and does not include all books annotated by Harvey (including the book Chaucer’s The woorkes of our antient and lerned English Poet, Geffrey Chaucer, edited by Thomas Speght), on the basis of some limited quantitative and qualitative analyses of Tusser’s Husbandrie, we can tentatively conclude that Harvey was mainly interested in the practical knowledge contained in this book rather than in its literary qualities. In this sense, he did not treat Tusser’s Husbandrie any differently from the other books in our corpus.