John Dee’s annotated books at the Royal College of Physicians, London

The AOR team is proud to announce that several colleagues and friends have agreed to write guests blogs for the AOR-website. This is the first of these guests blogs, written by Katie Birkwood, rare books and special collection librarian at the Royal College of Physicians!

The library of the Royal College of Physicians, London (RCP) is extremely lucky to number among its roughly 20,000 rare books the largest surviving collection of volumes once owned by the Elizabethan polymath John Dee (1527-1609). Though it is impossible to pin down the extent of the collection precisely, over 150 Dee’s surviving books can possibly be identified in the RCP collection. In 2016 the Royal College of Physicians hosted the first major exhibition dedicated to John Dee and his library, displaying forty of his books alongside objects said to have been used by him as part of his so-called “spirit actions” or “conversations with angels”.

Dee was one of the most intriguing an enigmatic characters of Tudor England: famous variously as a mathematician, a philosopher, an astrologer, a magician, a mystic, and even a spy. Dee was also a determined book collector and owner of one of the largest libraries in sixteenth-century England, eclipsing those of the universities of Oxford and Cambridge combined. Dee himself numbered his library at 3,000 printed books and 1,000 manuscripts, though the evidence of his own library catalogue suggests a more conservative total.

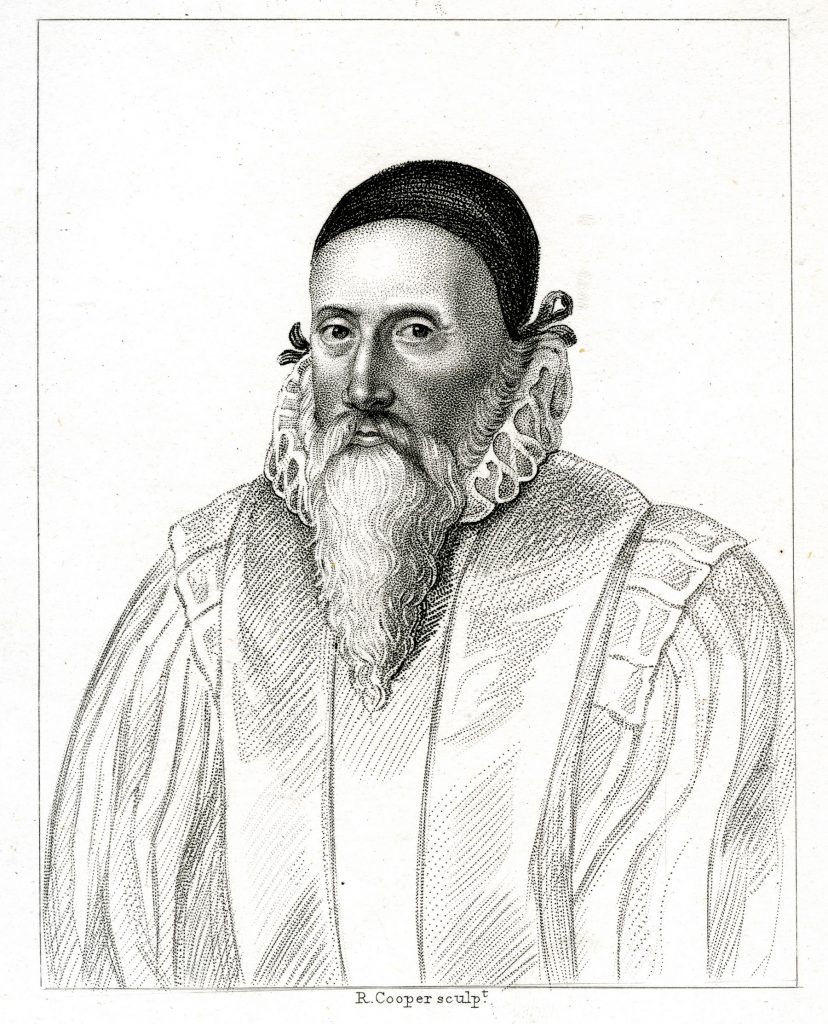

John Dee (1527-1609). Stipple engraving by Robert Cooper after unknown artist, late eighteenth to early nineteenth century

The contents of Dee’s library were as varied as his claims to fame, covering subjects as diverse as fencing, mineral baths, falconry, and botany. The library was his pride and joy; the product of many long hours spent in bookshops in London and across Europe, and Dee’s close relationship with booksellers’ agents who could hunt out the rarest volumes. Scholars from across the continent visited Dee’s house at Mortlake (a small village on the River Thames, seven miles west of the City of London) to consult with the great scholar and to read his books and manuscripts. Members of Queen Elizabeth’s court including sought his advice on matters ranging from the appearance of a comet in the sky to possible routes to China via a north-west or north-east sea passage.

In popular culture today, Dee is certainly best known for his spiritual and angelic activities. His attempts to communicate with angels are variously portrayed as the enthusiasms of a misguided old fool, the effects of unworldly academicism taken too far, or actively malicious attempts to rule over his fellow men. However, it is the different, but perhaps equally romanticized image of Dee as scholar, seated in his study with books spread out before him, that calls most strongly to me. Dee’s annotations – by turns painstaking and passionate – speak eloquently about Dee’s life, his interests, and his personality.

Sadly, the story of Dee’s library is not an altogether happy one. Dee left England in 1583 on what would turn out to be his longest overseas trip. He left in some haste, accompanied by Edward Kelley, his ‘scryer’ – a man employed to see angelic visions in a crystal ball or other reflected surface – his wife and children, and around 800 of his books. The rest of the library, along with Dee’s globes and astronomical instruments, were left in the care of his brother-in-law, Nicholas Fromond. Fromond was not a good custodian, and let thieves into the library during Dee’s absence. When Dee returned to Mortlake in 1589 he found his house and library in disarray: the shelves ransacked and many valuable treasures lost. The popular story that Dee’s house was attacked by a local mob is almost certainly untrue; his books were probably stolen by friends, associates, pupils and others who knew their intellectual and monetary value.

Fortunately, by piecing together evidence from within the books and from the library catalogue Dee made in September 1583, shortly in advance of his departure (now Trinity College, Cambridge, MS O.4.20), it is possible to reconstruct at least some of what was lost. Around 350 volumes are identified in Julian Roberts and Andrew G Watson’s 1990 catalogue of Dee’s library, and additions are posted to the Bibliographical Society website.

It seems that a certain Nicholas Saunder (possibly a Surrey MP) was one of the thieves, or at least a receiver of stolen goods. Several of the Dee books in the RCP library have Dee’s ownership mark obliterated, with Saunder’s own name written in nearby or over the top. Saunder’s library, including other books unrelated to Dee, passed by some means into the possession of Henry Pierrepont, first Marquis of Dorchester (1606-80), whose library was given to the RCP by his family after his death.

Signatures of John Dee and Nicholas Saunder on the title page of Jean Taisnier, Astrologiae iudiciariae ysagogica (Cologne: Arnold Birckman, 1559)

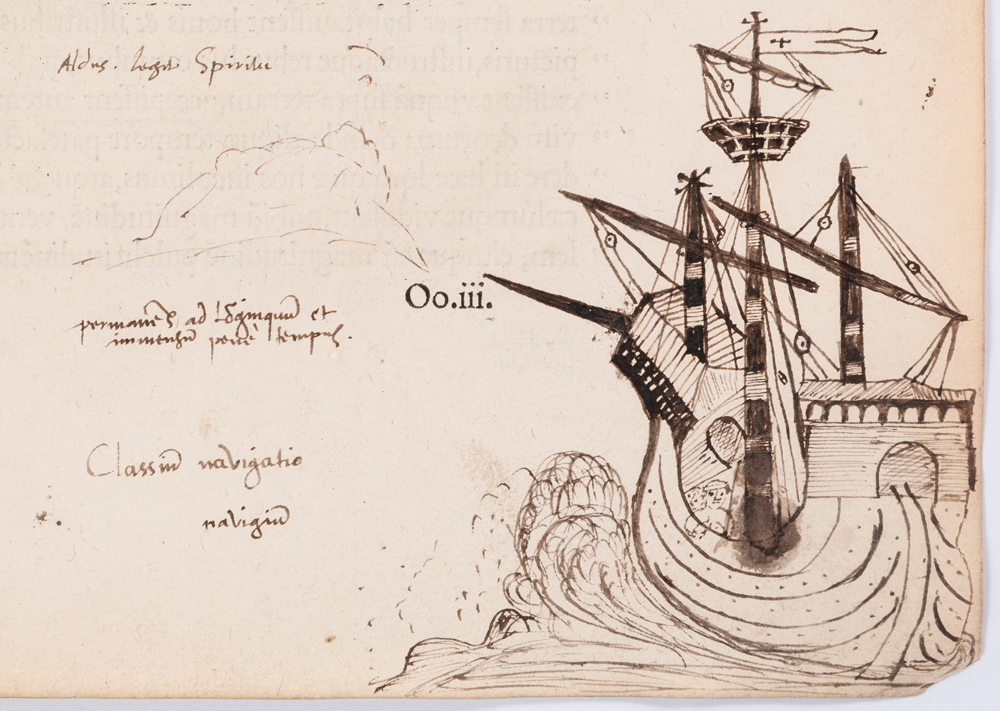

Twelve of Dee’s annotated books now in the RCP library have been chosen as part of the AOR phase 2. Included in their number are some of the most stunning and revealing books in the whole collection. A two-volume folio works of Cicero annotated by Dee as a student in the 1540s provides plenty of material for the modern scholar to chew over. There’s also more than one surprise as you turn its pages. In one instance, a sketch seems to resemble a Greek temple on a small island in flames: the nearby text of Cicero’s De legibus relates how the Persian king Xerxes set fire to the temples of the Greeks on the advice of the Persian magi. A larger instance of scholarly doodling is found in the same volume. In his De natura deorum Cicero quotes some lines from the Lucius Attius describing a huge bulk surging through the foaming seas. Next to this, Dee has drawn a most spectacular ship in full sail.

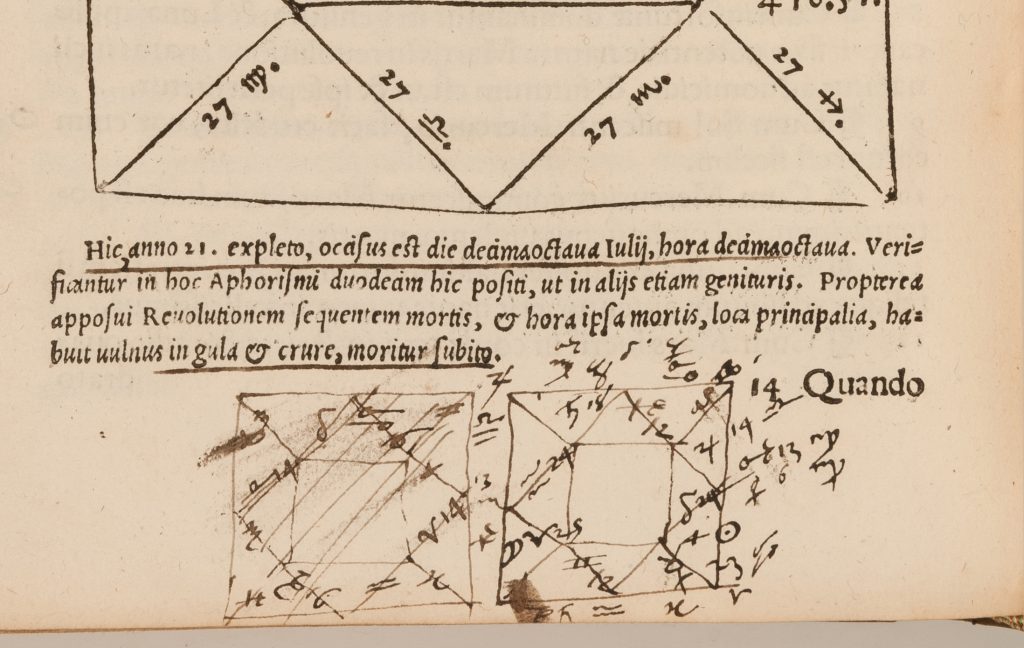

Less artistically adept, but no less interesting, are the astrological observations and calculations left by Dee in his copy of Girolamo Cardano’s Libelli quinque.

Girolamo Cardano, Libelli quinque (Nuremberg: Johannes Petrejus, 1547)

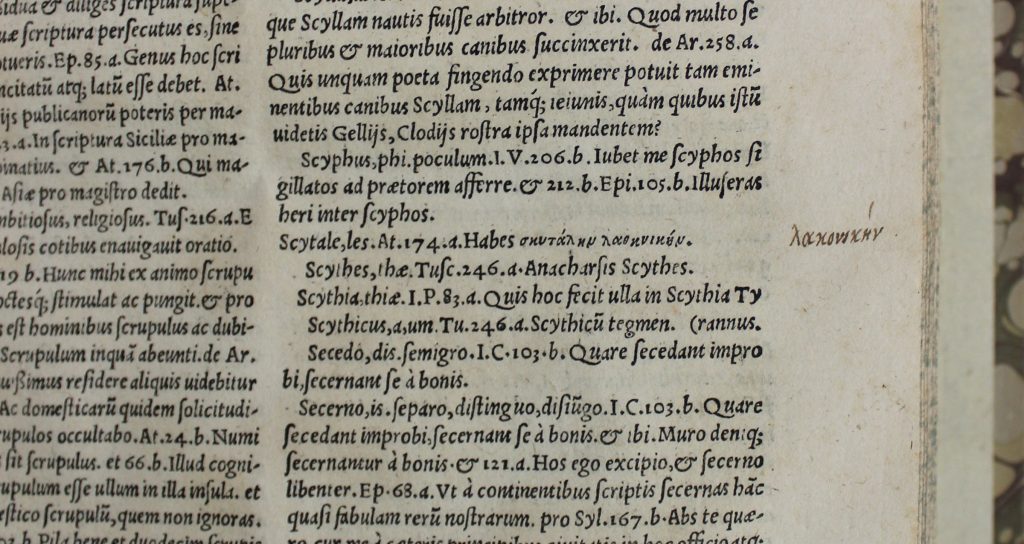

Aside from star objects such as the Cicero and Cardano, a point of interest appears in almost every book that retains any evidence of Dee’s ownership or use, not only the star objects. At first glance, there’s not much of interest in Dee’s copy of Mario Nizolio’s 1544 Latinae linguae dictionarium. We can probably assume that Dee acquired the book during his years as a student at St John’s College, Cambridge. There was once an ownership inscription on the title page, erased presumably by Nicholas Saunder, and there are very few annotations within the text. However, Dee does leave at least one trace. He notes the Greek word “Lakoniken” in the margin next to the lexicon entry “scytale”. Lakoniken is an alternative name for the Spartans, and the scytale is a tool the Spartans are reported to have used to perform transposition ciphers. In other words: this single annotated word might hint at Dee’s early interest in cryptography and code-breaking.

Mario Nizolio, Latinae linguae dictionarium (Basel: Robert Winter, 1544), sig. Xx2

I’m delighted that books from our collection are part of AOR, and am excited to see what more we can start to learn about John Dee and Elizabethan scholarly culture once all of his copious annotations have been transcribed.

Katie Birkwood, rare books and special collections librarian, Royal College of Physicians, London

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Julian Roberts and Andrew G. Watson, John Dee’s library catalogue (London: Bibliographical Society, 1990)