John Dee’s IDs

Blizzard aside, it was great to take AOR on the road for this year’s Renaissance Society of America (RSA) conference in New Orleans. Some great conversations emerged from discussion of Dee’s books, both in and out of the corpus. During the panel “Paging John Dee” Stephen Clucas pointed out a feature of Dee’s notes in his alchemical manuscripts that had caught my eye in the Geoffrey of Monmouth: a number of annotations bearing the initials “I.d.” Encountering these brought to mind a similar question for both of us: “why did Dee sign some annotations and not others?” and, more generally “what could this practice mean?”

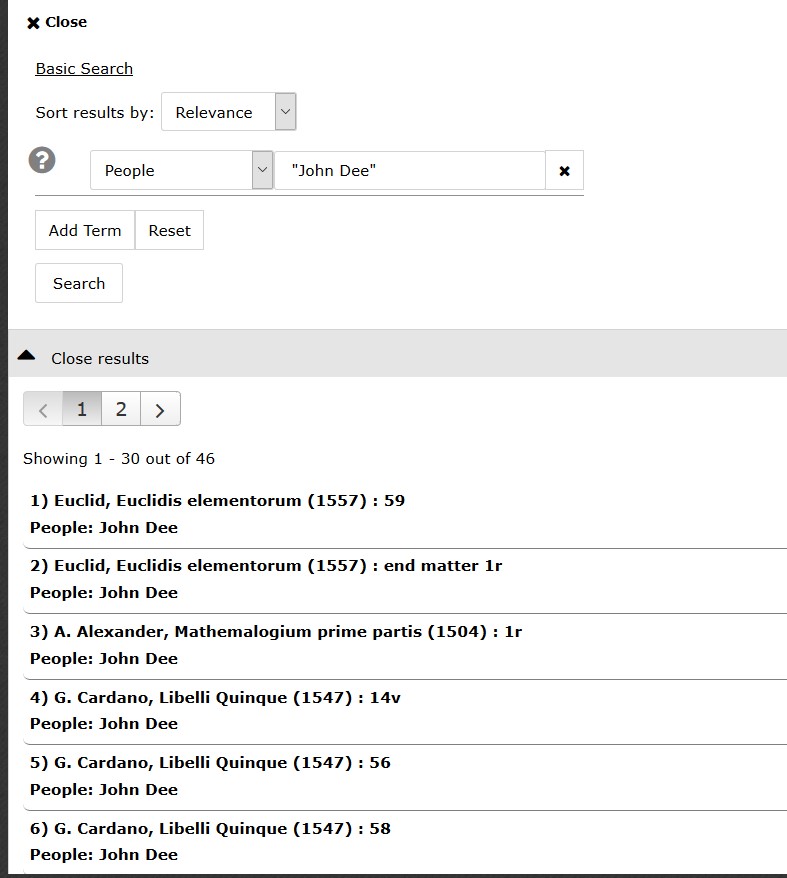

Since mentions of people in our individual annotations have been tagged, a quick search of AOR for “John Dee” (in quotation marks) in the person field of an annotation yielded 46 results across 16 of the 22 Dee books we have transcribed.

This search required a little cleanup, as it captured annotations that included references to Dee or his books, or Dee’s ownership inscriptions on a title page. Eliminating those revealed 28 signed annotations across 9 different books.

| Title | Number of Signed Notes |

| Monmouth, Historia regum Britanniae | 9 |

| Cardano, Libelli quinque | 6 |

| Paris, Flores historiarum | 4 |

| Maternus, Astronomicon | 3 |

| Walsingham, Ypodigma Neustriae | 2 |

| Paracelsus, Baderbuchlin | 1 |

| Pantheus, Vorachadumia | 1 |

| Cicero, Opera | 1 |

| Alexander, Mathemalogium | 1 |

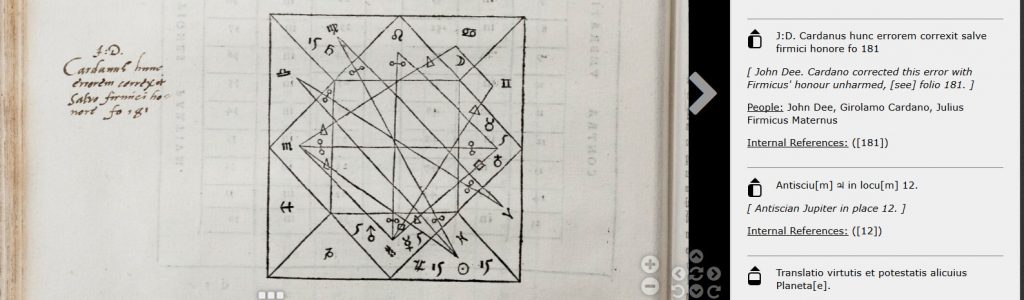

A few observations jump out from just the data. First, some texts appear to have been signed more heavily than others, with the Geoffrey of Monmouth signed the most extensively. Good to know that I noticed these notes after being beaten over the head with them (comparatively speaking) in the Monmouth. More specifically, these appear to be Dee’s way of editorializing and, in particular, problem-solving, as he does here, in explaining a correction to Maternus.

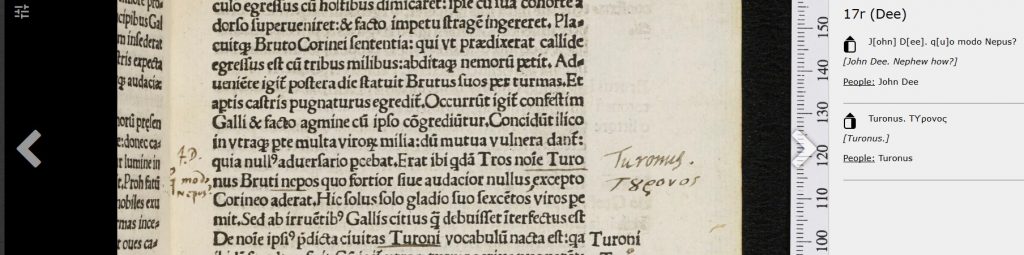

Or here, questioning the lineage of Britain’s earliest inhabitants.

Second, in the books with multiple signed annotations, the signed annotations appear to cluster together. Flyleaves and endpapers are consistent candidates, but within the body of the text, for example, we find a succession of signed notes in the Monmouth (fols 15-19) the Cardano (fols 56-63), along with two other signatures next to Dee’s work on tables.

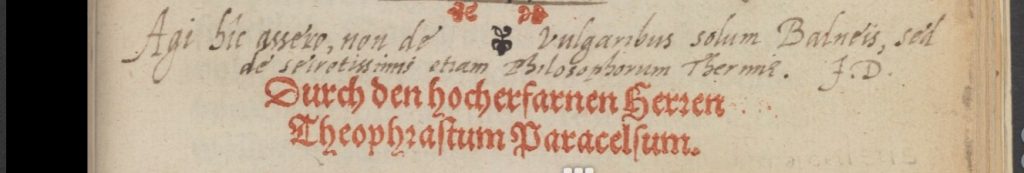

However, in the Cardano, some of these readings are dated, a trend observed in other books that Dee read around 1554-55 like the Mathemalogium, which records the date (and location) of Dee’s shared reading of the text in a Harvey-like note.

By contrast, only one signed annotation in the Monmouth is dated, chronicling Dee’s discovery of a corrected manuscript that supports his (earlier) assumption about ancient place names, discussed in this earlier post.

Some cautions here about the value of data alone – the clustering of signed annotations within any particular volume may be reflective of the overall clustering of annotations. Without broader context, we might not know how representative of a certain genre, time period, or topic this type of intervention is. It isn’t possible to locate all the books in Dee’s library catalogue, and even if we could (as I’ll leave for another post) we know that these aren’t the only books that he was able to put his hand on. Because such rich records survive, and because Dee was such a distinct annotator and intellectual figure, we know enough to locate books that aren’t mentioned in the catalogue that have Dee’s annotations.

However, searching the entire corpus cast light on tendencies that I never would have encountered had I just been looking at Dee’s “historical” books (or indeed, just the Geoffrey of Monmouth). His dating of annotations, in particular, seems to have peaked at an earlier period than his notes in the Monmouth volume. It also allows us to observe Dee actively engaging in conversation with his books (clarifying material and posing questions) and, we must assume, the other readers that encountered them in his library. Even if these outputs don’t fit into neat or, for that matter, readily apparent categories, they allow us to ask questions that wouldn’t be askable of one book, or perhaps even one note in one book. Pulled together quickly, this zoomed out view of Dee’s reading helps test initial questions like “why would Dee ‘authorize’ his own notes?” and tie them to new discoveries in the field.

This approach might also help scholars to identify practices to investigate beyond the corpus. On the same RSA panel, Jenny Rampling showed how far Dee’s notes might travel, tracing one out of the margins of an alchemical manuscript and into a printed book, via a fair copy made at the request of Dee’s traveling companion and “seer,” Edward Kelley (1555-97). If the notes in these books were Dee’s intellectual property, the Q&A session also revealed an early example of its theft: Nicholas Saunder, who made off with books from Dee’s library and tried to disguise their origin (as he has in the Pliny), appears to have written over Dee’s initials in the marginalia as well. Just as we “encounter” Dee in the margins of his books, so too did his contemporaries. What might their impressions been of him?