‘Pro se quisque’

Transcribing all of Harvey’s annotations is not always an easy—let alone enjoyable—task, mainly because of his obsession for detail, as a result of which some transcriptions seem to be never-ending—or at least it surely feels like that. However, precisely because of this level of detail, when transcribing one sometimes encounters particular annotations that are likely to be overlooked when studying Harvey’s annotations, especially because we, almost reflexively, tend to direct our gaze to the marginal notes, which are seen as (and often prove to be) the richest and juiciest source of information.

One of these particular annotations that attracted my attention are the words “pro se quisque,” which Harvey underlined in his copy of Livy’s history of Rome. I was intrigued by this, not so much because of the meaning of the words (“everyone for himself”), but because of the fact that Harvey underlined it with dots instead of a more or less straight line. This prompted me to add another variable to the method attribute of the underline tag, further expanding the search options.

When continuing my transcription of Livy’s history of Rome, I was surprised to see that underscored the words “pro se quisque” more often; we have just finished transcribing Livy’s history in its entirety (!!), and it turns out that he underlined this phrase twenty-five times. Most often he would just underline these three words (fifteen times), whereas ten times he underscored them as part of a slightly larger set of words. Underscoring these words by using dots, which initially attracted my attention, proved to be quite uncommon (only five times), as he normally preferred to use lines.

Interestingly, the words “pro se quisque” are not just underlined in the printed text, but also appear in five marginal notes. In the first of these notes, Harvey wrote: “Everyone [strove] for himself, with no king at this time. The people favoured their power, the Senate its authority. The basis was of the people. Yet Romulus was the master and the common people were the slaves, just like here” (p. 9).

The lack of strong leadership, and its negative repercussions for the Roman state, are echoed in other marginal notes as well: “For a nation that was the richest, most active as well as the shrewdest in the world it was not difficult to command kings and dominate the world. How many kings there are in one popularist city? Each one [strives] for himself.” Elsewhere he wrote: “The Roman offices served the use of the republic, not the grandeur of individual persons. Every one for himself, and those who cannot be Scipios abroad, want to be Petiliuses at home. And they have the nerve to taunt those by quibbling who they do not dare to rival by deserving well” (p. 689); and “A skillful move in a difficult situation. Everyone [strives] for himself, [see] above, below. Shyness in holding power and dealing with matters is for a boy, not a man” (p. 76).

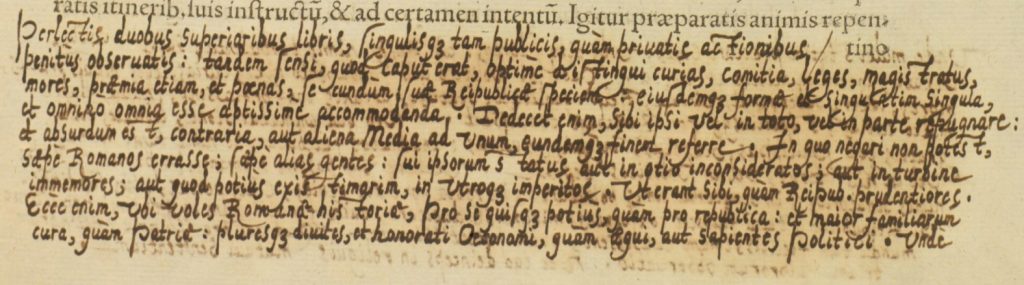

It is also interesting that the underscoring of the words “pro se quisque” and the marginal notes that contain this phrase never coincide (i.e., appear on the same page): it was a running theme, a topic in which Harvey was interested and which he addressed throughout the book—sometimes in the form of underlining, sometimes in the shape of a marginal note. It certainly was always on his mind, for after “having thoroughly read the above two books . . . I have come to understand in the end, that it was pivotal to distinguish most clearly the curiae, assemblies, laws, magistrates, customs, even the rewards and punishments according to the type of Republic, and its form, each individually, and that all should be fitted in entirely, in the most suitable way.”

Harvey concluded that this had not always been the case throughout Roman history, “so that they [the Romans] were more prudent for themselves than for the Republic. For look wherever you wish in Roman history: everyone [strives] more for himself [my italics], than for the Republic; the devotion to the household is greater, than that to the fatherland; there are more rich and respected housekeepers than fair and wise politicians” (p. 63).

The lengthy note continues on the next page, and Harvey argued that if the Romans had tailored their laws and political offices more closely to the nature of the Republic, this would have contributed to the well-being and stability of the state. This certainly was an important insight, and as the marginal note continued, Harvey wrote: “And for this consideration Philip Sidney, the prominent courtier, thanked me generously, and he openly acknowledged that he had never read anything of such importance either in historical or political works. That he had observed far and wide Romans who were too much senatorial in a popularist Republic and ones who were too much popularist in a Senatorial Republic, ones who were not royalist enough in a monarchy, citizens rather than subjects. And that he had no doubts whatsoever that if they had adapted themselves to the constitution of the State, that they would have come out as the strongest nation, the most successful and powerful people in the world. And this was our most important observation about these three books. . .” (p. 64).

Here the full meaning Harvey attributed to the phrase ‘pro se quisque’ is disclosed: it denotes not only people striving for their own interests at the expense of the larger, public good, but also people acting contrary to the constitution of the Republic, disturbing its balance and harmony and creating internal turmoil.

Here the full meaning Harvey attributed to the phrase “pro se quisque” is disclosed: it denotes not only people striving for their own interests at the expense of the larger, public good, but also people acting contrary to the constitution of the Republic, disturbing its balance and harmony and creating internal turmoil. Interestingly, in only two of the other eleven books in our corpus did Harvey either mention or underscore the words “pro se quisque.” He did this in two marginal notes, one in Domenichi’s Facetie (**2[r]) and one in Guicciardini’s Detti et fatti (p. 48). In both cases, the context in which this phrase appears is different from the context (and content) of the marginal notes in Livy’s book.

Although more research could be done—e.g., Did he underline all instances of “pro se quisque” in the printed text? What was the context in which this phrase was used in the printed text? Why did he use various forms of underlining? Are other marks used to highlight this phrase?—this example neatly shows the links between various forms of readers’ interventions, in this case underlining and marginal notes. For a transcriber, that’s probably the most valuable outcome of this small case study: it shows the benefit of having tagged all of Harvey’s interventions, which, if only for a moment, lightens the burden of what sometimes can be an arduous task.