The Archaeology of Reading Hamlet

This past summer I had the opportunity to use the Archaeology of Reading to help teach a course for a group of community college students visiting Johns Hopkins. This course was part of a national, Mellon-funded initiative to bring together community colleges with research institutions such as Hopkins in order to introduce students to high level research environments in both sciences and the humanities. I was tasked with developing a syllabus that would make use of the Archaeology of Reading as a way to engage students directly in digital humanities research.

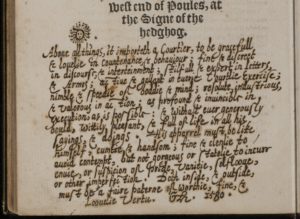

The plan was to work with the students to analyze and transcribe an annotated copy of Hamlet currently held at Hopkins:

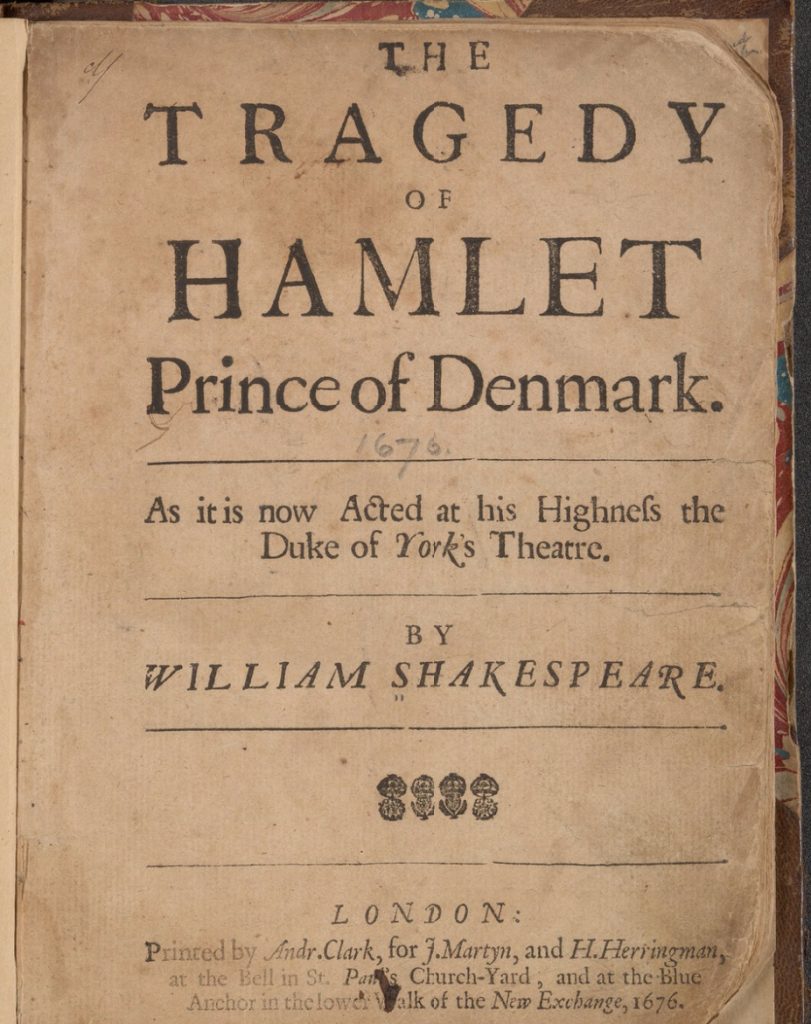

These marginalia and textual changes are found in a copy of the 1676 edition. They were made by the 18th-century English actor and theater director, John Ward.

I produced a syllabus which divided the course into three sections:

1. Reading Hamlet and learning about Early Modern England

2. Learning about digital tools and environments

3. Transcribing the annotations using the workflow developed during AOR phase 1

For the first section of the course, spent a couple of weeks going through the play, talking about the plot, analyzing the characters, and discussing our interpretations. We made use of a good critical edition of the text from Oxford Classics. This edition offers useful footnotes for explicating difficult language and passages.

The Oxford Hamlet also provides an excellent introduction to the complex printing history of the play. In reality, there are three early printed editions of Hamlet, all of which contain substantial differences between them: the “Bad” Quarto (Q1) from 1603, the “Good” Quarto (Q2) from 1604, and the First Folio (1623).

The Oxford edition reproduces the text from the First Folio, while also including discussions of Q1 and providing important sections of Q2 in an appendix. As a result, not only did we discuss the play itself, but we also considered one of the central themes of scholarship dealing with marginalia, the varying interpretations and modes of reading across different periods.

From there I introduced the students to several online resources, such as Early English Books Online and the Archaeology of Reading. With EEBO, we were able to start looking at the format and layout of early editions of Shakespeare.

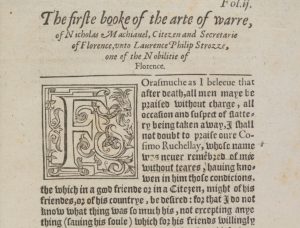

To acclimate them to rather alien fonts and to help prepare them for transcribing the Hamlet marginalia, I introduced my students to the AOR viewer. I asked them to practice transcribing sections of printed text from Machiavelli’s Arte of Warre (1573), which has a rather tricky font for those unaccustomed to looking at sixteenth-century books.

I then asked them to turn to Gabriel Harvey’s marginalia. We looked at one of his longer notes, found in an English translation of Castiglione’s The Courtyer (1561), which describes the ideal characteristics of a courtier. It also proved to be an interesting moment of comparison with the character of Hamlet, described by Ophelia as “the glass of fashion and the mould of form.”

After some practice in transcribing print and handwriting, I divided up the text into chunks of about 11 pages and assigned them to each of the students. I had eight students total, so this proved to be a very manageable division of labor. The marginalia themselves were also fairly straightforward:

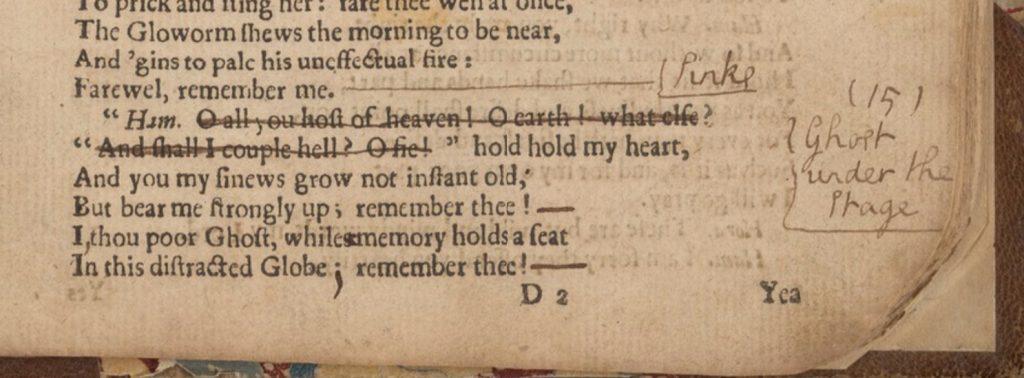

Many of the notes—perhaps unsurprisingly for a stage manager—dealt with the entrances of characters, including where they might be positioned. In this instance, the ghost ought to be “under the stage.”

Yet modifications to the text, at least to this extent, was not something initially included in the development of the AOR transcription paradigm. Harvey and Dee, though often engaging actively with their reading material, are not particularly interested in correcting or changing the printed word to make it easier to perform. With Ward, there were several ways of “interacting” with the text:

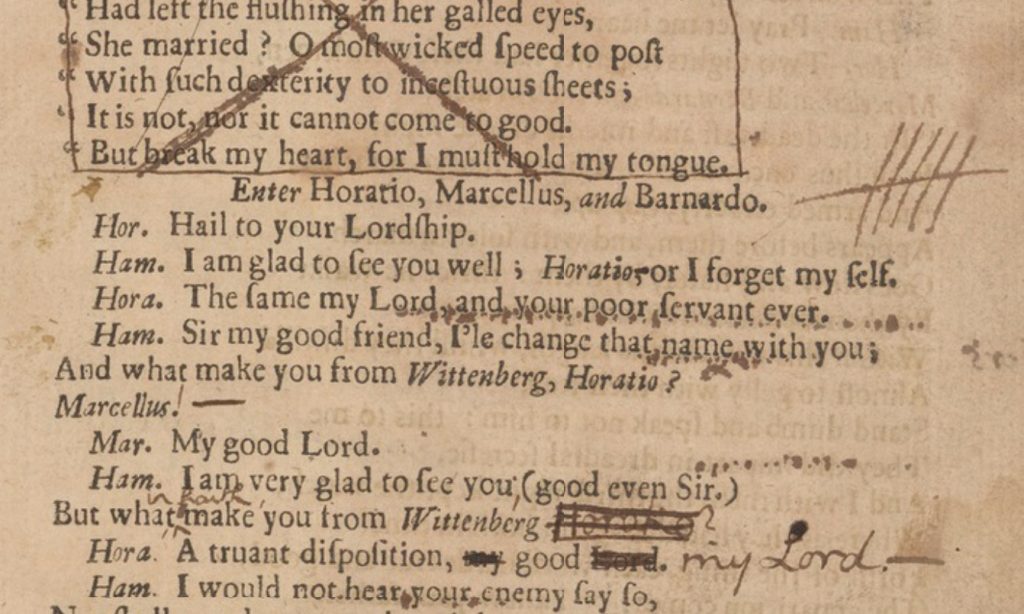

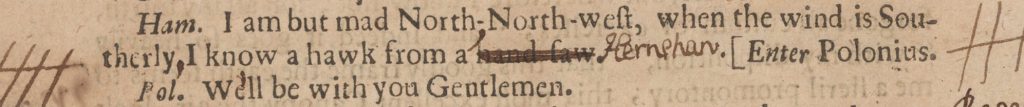

In this example we see several novel elements:

1.a large deletion of sections of text

2. a new symbol (looks like a long line with hatching)

3. the replacement of words and phrases (“my good lord” → “good my Lord”)

4. insertion of new elements, such as punctuation (ubiquitous in Ward’s promptbook)

To capture this information, I had to slightly modify our XML schema by incorporating a new tag and including a new symbol. This work was not particularly challenging, and our programmers were able to adapt to this different schema relatively easily.

To help the students in their transcriptions, almost all of whom had never worked with any sort of machine-readable language, I produced a simple transcriber’s manual (a pale imitation of the work done by Jaap and Matt for AOR). I also created a template XML file, which contained examples of the basic elements needed to transcribe a page of the Hamlet. All the students would have to do is copy, paste, and modify in order to capture the relevant information. These files, as well as the final XML files, were uploaded to a GitHub repository, which basically follows the same format as the AOR one.

Overall the students were quite invested in the work, although it took awhile to fall into a rhythm for accurately transcribing texts printed over three hundred years ago. We used class sessions as transcription workshops, where students were able to make use of laptops provided by the library. I was able to answer any questions the students had, and being together made it easier for them to check each others work.

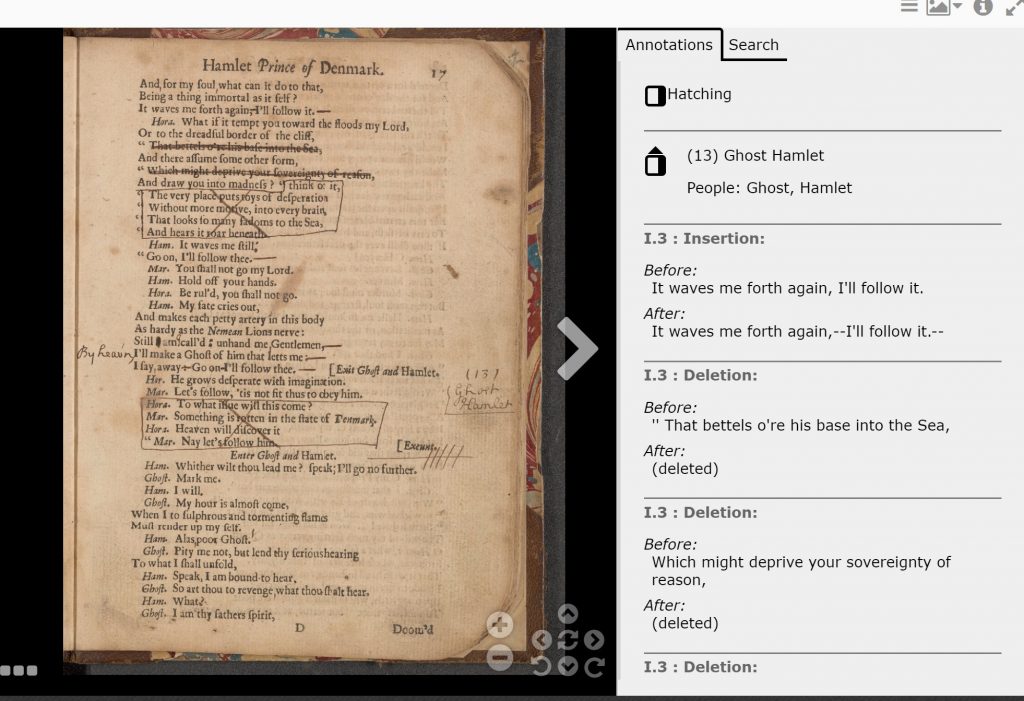

Eventually the students produced XML files for the entire work, which can be found here, on a separate instance of the AOR viewer.

The interface is identical to that of AOR phase 1, although it is immediately clear that Ward’s style of annotation clearly functions much more differently than Harvey’s or Dee’s.

In addition to producing a tool for scholar’s to consult when researching early annotated editions of Hamlet, the students also stumbled across interesting elements in the text. For instance, one student found one of the earliest examples of an emendation to a particularly obscure passage in the play:

After doing some research, we discovered that Ward’s emendation (“hernshaw”) does not derive from any earlier editions of Hamlet but rather represents an attempt to clarify the ambiguous identity of “handsaw,” which is actually a bird and not a carpenter’s tool.

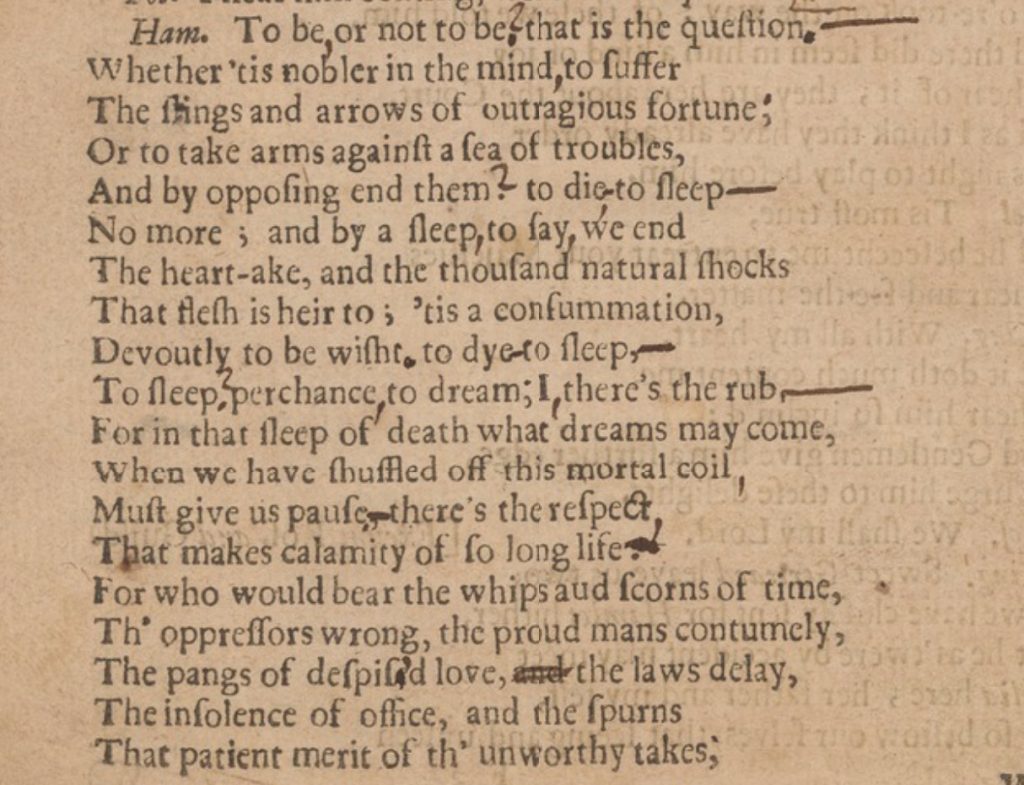

Another student focused on the interesting punctuation in Hamlet’s famous soliloquy in Act 3:

This student ultimately gave a fascinating presentation during a symposium in August on the different uses of punctuation in this very speech. Unsurprisingly, John Ward is relying on grammatical and theatrical conventions peculiar to his own epoch. I would say that the transcription process, however slow going it might have been, actually allowed the students to get much closer to the text than we had during our close reading of the play.

In addition to reading and transcribing Hamlet, we were also treated to a series of fantastic presentations from researchers at Hopkins working on AOR. Earle Havens introduced the class to the digital humanities and the use of digital tools for visualizing history, Jaap Geraerts skyped in from across the pond to talk about the process of developing AOR’s XML schema, Mark Patton described how programmers and humanists work together to make materials accessible to everyone, and Neil Weijer gave multiple presentations on early modern England, the history of the book, and Shakespearean forgeries.

We also had the opportunity to go on several trips to visit various nearby labs and libraries to expose students to relevant and interesting research materials, as well as the many kinds of skilled professionals and scholars who work around them. We got to see some surgery performed on early modern book-binding structures in JHU’s Conservation Lab; we learned about print-making and early Shakespearean prints at the Baltimore Museum of Art; at the Evergreen Library, the students learned about the varieties of early books, including Audubon’s Birds of America in its enormous elephant folio edition. In the last week of class, we visited Washington D.C., where we went to the Library of Congress to see rare objects such as the first map containing America and Thomas Jefferson’s library. We also visited the Folger Shakespeare Library, where we were given a tour of the some of the library’s annotated Shakespeare texts. We also stopped by the ongoing exhibition on painting Shakespeare across time, an exhibit definitely worth seeing, especially since it lets you try on costumes:

The summer course turned out to be excellent research experience for the students, who were able to engage in more “traditional” methods, as well as explore and develop new types of digital scholarship. They were able to collectively explore the text of Hamlet at a high level of detail, learn about the history of the book (including the methods of early printing, typography, and printmaking), and develop an understanding of basic digital humanities tools, particularly the use of XML to help capture marginalia and textual modifications. AOR turned out to be a robust pedagogical tool. It immediately provided a platform for the easy exploration of early modern books, typography, and paloegraphy. More fundamentally, the process of producing a transcription for a new annotated book allowed students to develop new digital skills as well as hone their ability to carefully attend to the word on the page. Transcribing proved to be immensely useful in helping students both learn about the collective nature of research, as well as explore in a new way one of the most fascinating texts of English literature.