In late November 2016 the Charles Singleton Center for the Study of Premodern Europe hosted and the Alexander Grass Humanities Institute co-sponsored at Johns Hopkins University campus-wide rollout of AOR, drawing a large group of faculty, graduate students, librarians, and members of the AOR team, in particular several interesting questions from the audience on infrastructure and DH sustainability fielded by the Sheridan Libraries’ Digital Research and Curation Center staff.

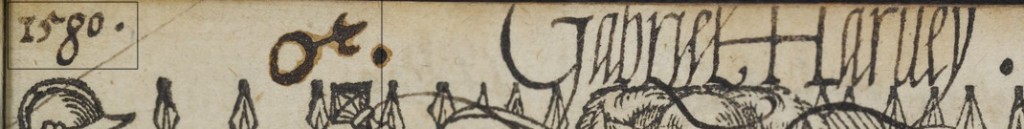

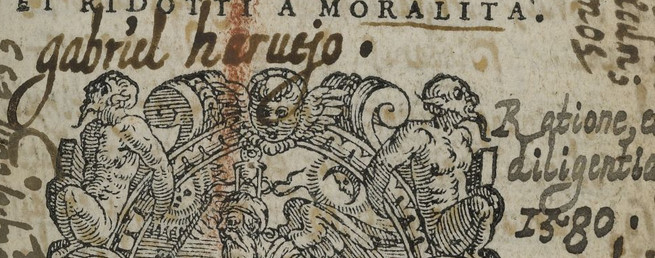

The panel started off with a wonderful retrospective from Tony Grafton on the history of obsessive-compulsive early modern readership and, more specifically, the history-behind-the-history of their often cited essay “Studied for Action: How Gabriel Harvey Read His Livy.” A large projection screen returned the gathered crowd to Princeton over 25 years ago and a wonderful, smiling photograph of Lisa Jardine accompanied by Tony’s warm recollections of their many long hours together pouring over Harvey’s notes in Livy’s history of Rome in the rare book reading room at the Firestone Library…and some particularly loud and heated debates about what Harvey was getting at, which they both enjoyed immensely. (There was no mention of librarians shushing anyone on those several occasions, but one can imagine.) Tony also recalled an essential conversation they had together with his Princeton colleague, Robert Darnton, on whether marginalia could ever really be considered a representation of the history of reading. Out of that fruitful discussion was born the organizing principle of the “bookwheel” that stands at the heart of AOR, and indeed forms the logo and the name of this blog on the AOR website. It is the idea that marginalia not only richly preserve the reading experience of a learned annotator through his immediate responses to printed texts; but, perhaps just as importantly, that they also present scholars with direct evidence of how someone like Harvey deployed the fuller resources of his personal library in the process. Harvey’s marginalia preserve, metaphorically speaking, the motions of a bookwheel filled with a multiplicity of essential books in the history of scholarship, ancient and early modern.

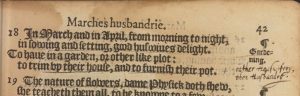

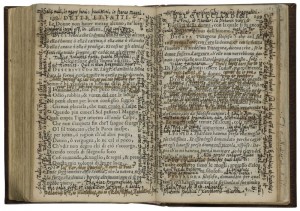

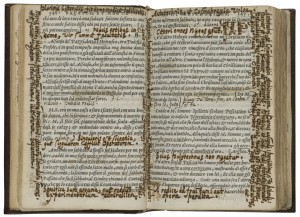

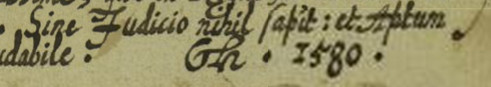

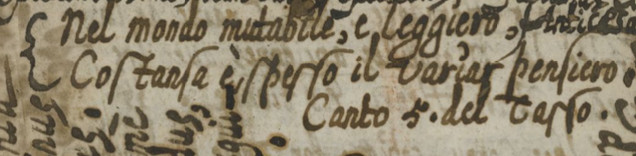

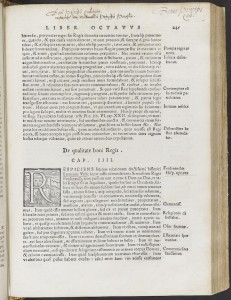

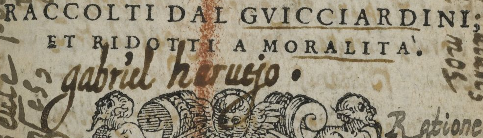

Harvey’s ready engagement with the contents of his uniquely formed, well-stocked library of hundreds of volumes was indeed “Studied for Action” as he “drew out all the garrisons” from his bookshelves (a phrase Harvey underlined in his copy of Machiavelli’s Arte of Warre) in order to turn his reading into tools to affect the world in his own moment: as an aspiring courtier, and as a “professional reader” advising, for example, Sir Philip Sidney on his forthcoming embassy to Prague by reading together from his annotated copy of Livy. Harvey’s compulsive, marginal cross-referencing between different books at his disposal—at times seeming to mark them simultaneously in reference to one another—has become an more frequent theme of our work since the AOR Viewer went live a few months ago, allowing us to search and track this activity systematically within individual books, and across all the books, in the AOR corpus. It will be fascinating to see the extent to which John Dee did the same in the nearly two-dozen annotated books from his library that will form the work of AOR Phase 2.

Earle Havens was up next with his own rendition of “The Archaeology of the Archaeology of Reading,” beginning with a Seneca’s old metaphorical saw about hard-reading scholars as busy bees: “We ought not only to write, nor only read…it must be gone back and forth from this to that in turns, so that whatever is collected by reading, the stylus may render in form. We should imitate the bees, as they say, which wander and pluck suitable flowers to make honey (Epistulae Morales, 84).

There were in fact many milestones of precisely this same kind of selective wandering through books, of learned readers plucking out purple passages, and making intellectual honey: from the “polyhistors” of Greco-Roman antiquity (Stobaeus, Aulus Gellius, Solinus), and medieval encyclopedists and compilers of florilegia (Isidore of Seville, Vincent de Beauvais, Thomas of Ireland), to the essential Renaissance hunter-gatherers and organizers of loci communes (Agricola, Erasmus, Melanchthon…their pedagogical tracts prescribing organized programs of reading were printed and reprinted as De ratione studii anthologies throughout the middle decades of the 16th century). Attention then turned to the idiosyncratic process of building up a digital corpus with the full advantage of an AOR dream team comprised of Tony, Lisa, and all our colleagues at JHU, Princeton, and UCL, and to the nuts-and-bolts of pulling all that talent together to make DH honey. This is one way of thinking of the AOR Viewer: as a kind of composite tertium quid comprised of the best gathered thoughts and efforts of a diverse and committed research team.

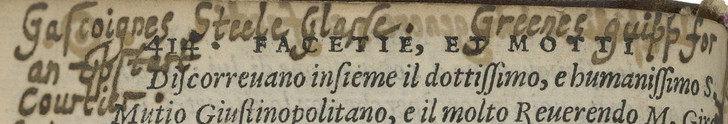

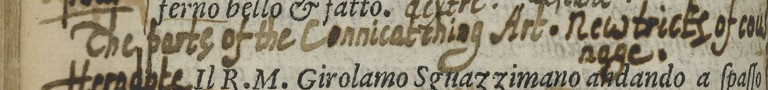

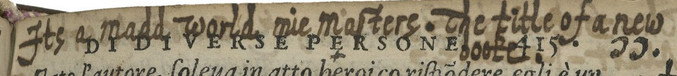

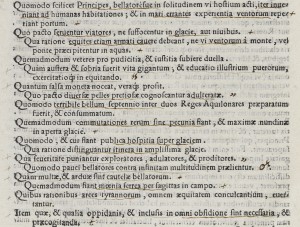

Once the old-timers wrapped up their reflections, the panel concluded with a firework display of marginalia from JHU Research Assistant—and long-suffering transcriber of the vertiginous marginalia in Harvey’s Domenichi and Guicciardini volumes—Chris Geekie. Chris carried the show from life and archaeology in the margins to the realm of imaginative literature, taking as his case study the myriad ways in which Harvey invoked the French agent provocateur of many aspiring Renaissance wits, François Rabelais. Taking as his starting point the broad view, both modern and early modern, that Rabelais was an irreverent, potentially atheist, author, Chris asked whether that notion held up in Harvey’s repeated references to Rabelais across his marginalia, and further afield in Harvey’s printed polemics.

The AOR viewer’s search feature reveals that Harvey hardly held one stable opinion of Rabelais, and that his tone vis-à-vis Rabelais morphed according to the context of the particular texts and contexts to which he responded pen in hand. Sometimes he praised Rabelais as a supreme wit, at others he emerges as a dangerous author for readers who lack a cautious mind. Interestingly, Rabelais’s name almost always appears in the AOR marginalia in conjunction with other major contemporary authors—Pietro Aretino, Guillaume Du Bartas, and Philip Sidney—suggesting a more nuanced view of the French author than just as arch-literatus or arch-irreligious. He could also be just one star in a larger constellation of Renaissance literati whose works collectively represented to a reader like Harvey a sequence of rich literary tropes, forms, and topoi.

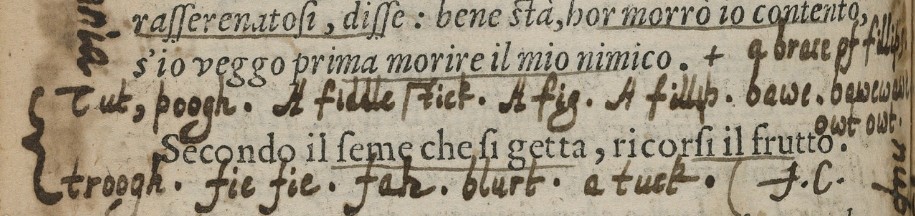

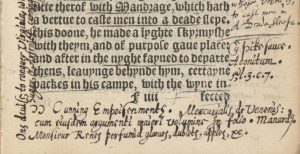

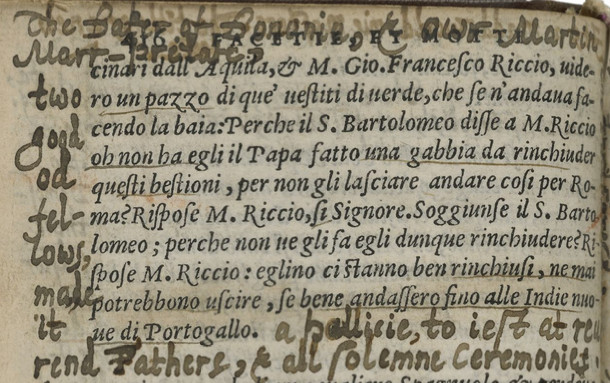

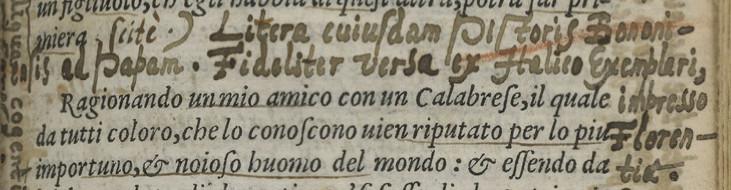

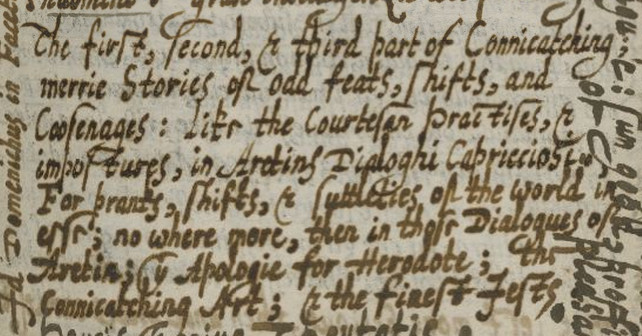

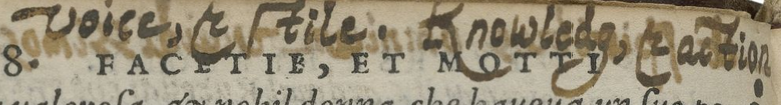

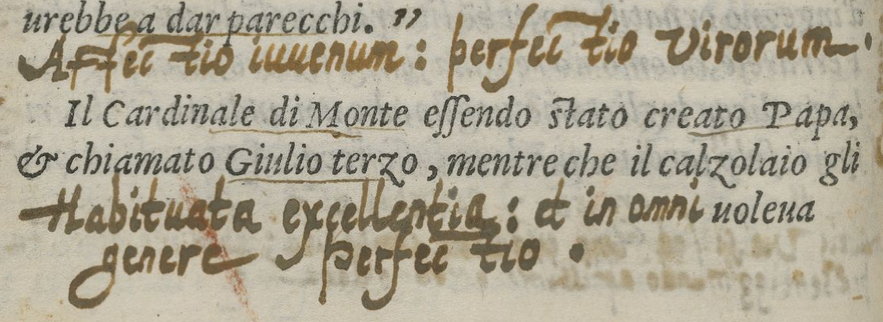

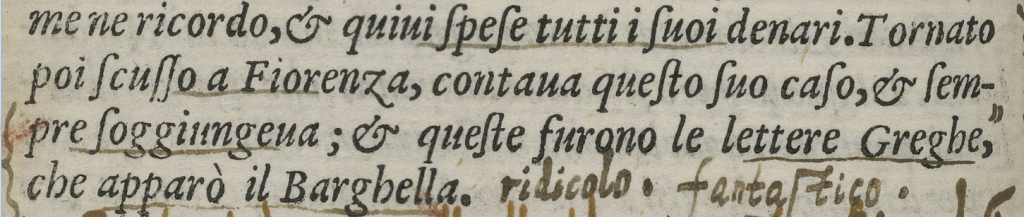

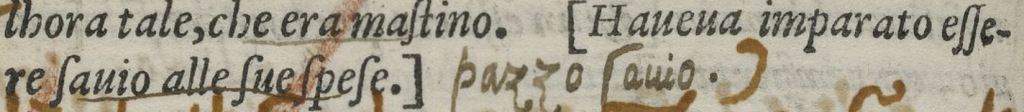

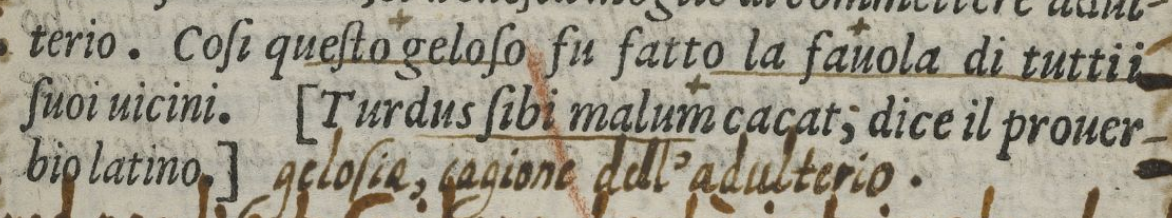

Another convention was shot through with holes by Chris’s Harvey/Rabelais investigation through the AOR viewer: the scholarly distinction often made between Harvey’s apparently distinct public opinions—which he shared with full-throated ease in his public “quarrel” in print with the University Wit Thomas Nashe—and the personal, and presumably less performative, thoughts he was supposed to relegate to the margins of the books in his private library. At key points of overlap between Harvey’s marginalia and his printed polemics, Chris found this public/private distinction also to fall apart. A passage in Harvey’s Pierces Supererogation or, A New Praise of the Olde Asse (1593) unleashed a stream of ad hominem venom on Nashe, reducing him to “the bawewawe of Schollars, the tutt of Gentlemen, the tee-heegh of Gentlewomen, the phy of Citizens, the blurt of Courtiers, the poogh of good Letters, the faph of good manners, & the whoop-hooe of good boyes in London streetes.” Distinct echoes of this bizarre, Rabelaisian wordplay appears just as loudly in the middle of one of Harvey’s highly annotated pages of Lodovico Domenchi’s Italian joke book in the AOR corpus:

Clearly there is much more going on in Harvey’s two spheres of writing than has been generally realized, or realizable absent our new capacity to search thoroughly through his marginalia in a digital format. Even just a quick search for a literary persona like Rabelais in the AOR viewer, allied with additional research beyond the digital corpus, can reveal traditional public/private and print/manuscript binaries to be latter-day interpretive square pegs ill-fitted to history’s many round holes.

![[My Asse confuted.]](http://archaeologyofreading.wpshared.library.jhu.edu/wp-content/uploads/sites/21/2015/03/myasse.png)