Digitization and its discontents

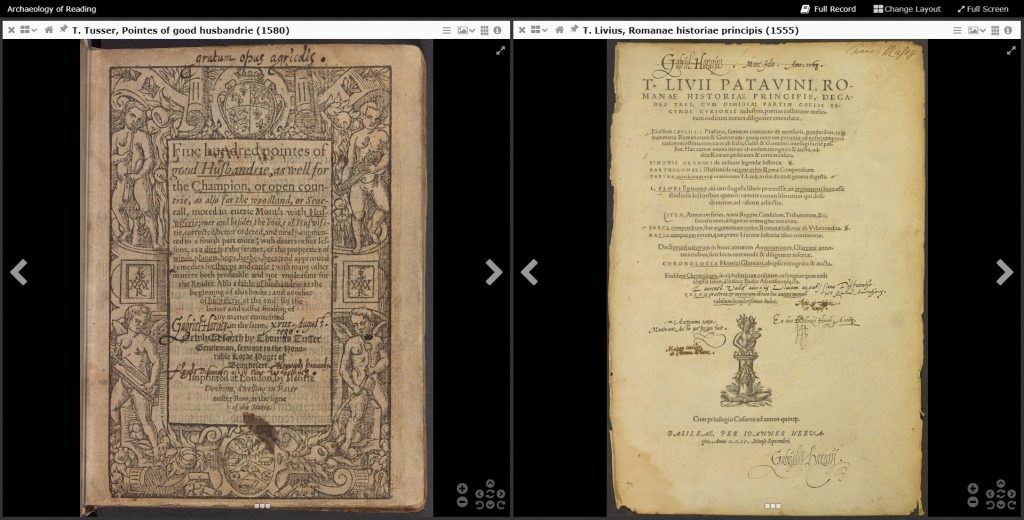

In an earlier blog, Matt Symonds discussed some losses which are inevitably part of the process of digitization. The material aspects of books in particular – their size, weight, feel and, indeed, smell – are difficult or impossible to convey on a screen. Consider, for example, the title pages of Livy’s History of Rome and Tusser’s Husbandry as displayed in the AOR viewer. The size of the images is exactly the same, obscuring the actual differences in format (the copy of Livy’s History owned by Gabriel Harvey is a hefty folio, whereas Tusser’s Husbandry is a quarto).

In spite of the loss of some of the physical qualities of a book when transferring it to a digital environment, in most cases the pros of digitization still outweigh the cons. Above all, the increased and ready access to books (as well as to archival documents) is a major stimulus to scholarship as it overcomes all kinds of financial, spatial, and institutional hurdles.

When doing research on Catholic marriage practices in the seventeenth-century Dutch Republic, for example, a manuscript letter made mention of a tract written by the priest Joannes Stalenus. A quick search on google returned a digital version of Joannes Stalenus’ Dissertatio Theologo-Politica hoc tempore discvssv & scitv necessaria […] (Cologne, 1677), a book recently digitized by Google (see here). Due to the existence of this digital copy, I did not have to hunt down the book in research libraries in the UK or abroad, but could directly access it. The online availability of a digitized copy of this book was so useful because I was primarily interested in the contents of this book, and not in the physical or other aspects that are specific to this copy. In other words, a digital version of any copy would have sufficed for my purposes (as long as the quality of the digital copy is up to scratch).

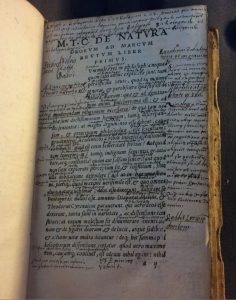

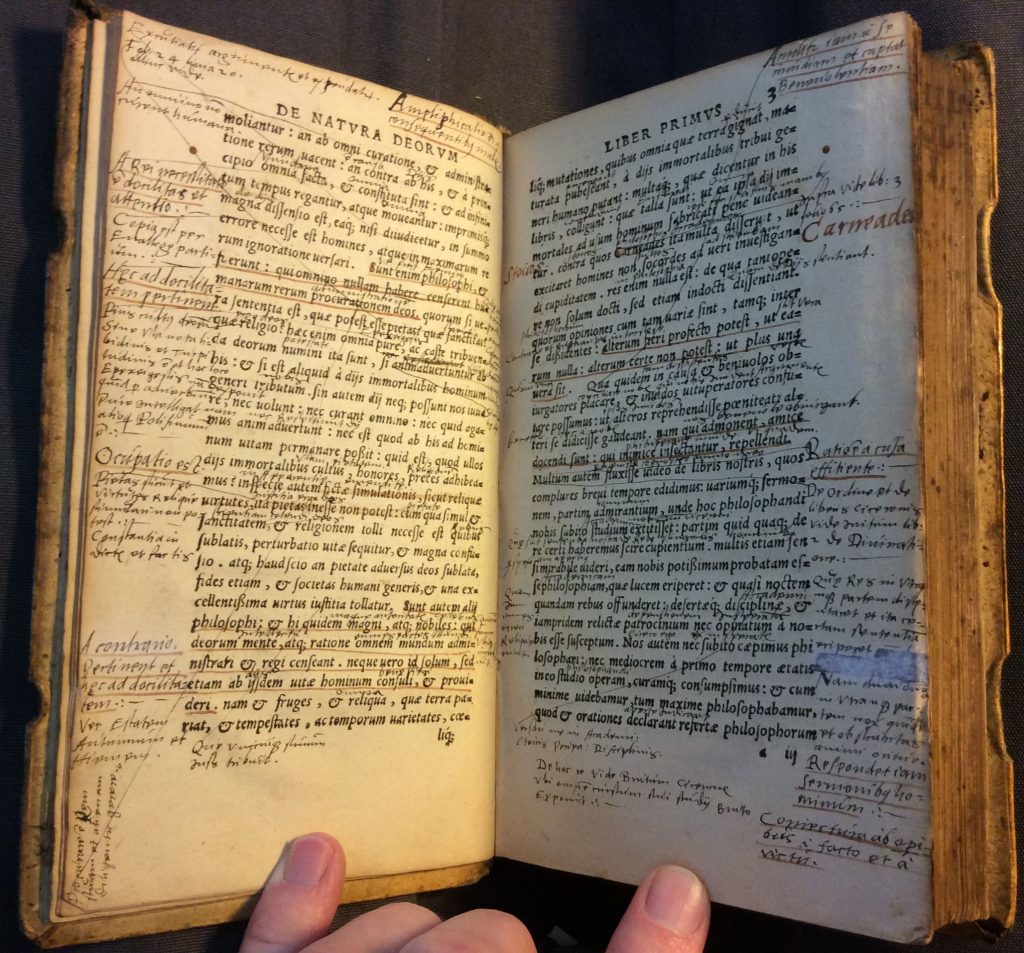

As a scholar of historical reading practices, however, I’m very much interested in particular copies of books, namely those which contain reader interventions, physical remnants and traces of the ways in which people used their books in early modern Europe. This morning I wanted to call up a particularly densely annotated copy of Cicero’s Librorum philosophicorum uolumen primum […] (Strasbourg, 1541) which is part of the collections of the British Library (BL) (shelf mark 525.c.1,2.). In the spring of 2016 I stumbled upon this book when searching the holdings of the BL for books annotated by the Elizabethan polymath John Dee, but soon realized that it was not Dee who annotated this book (to my great relief, I have to admit, since transcribing this book is a gigantuous task). This is what some of the pages of the book look like:

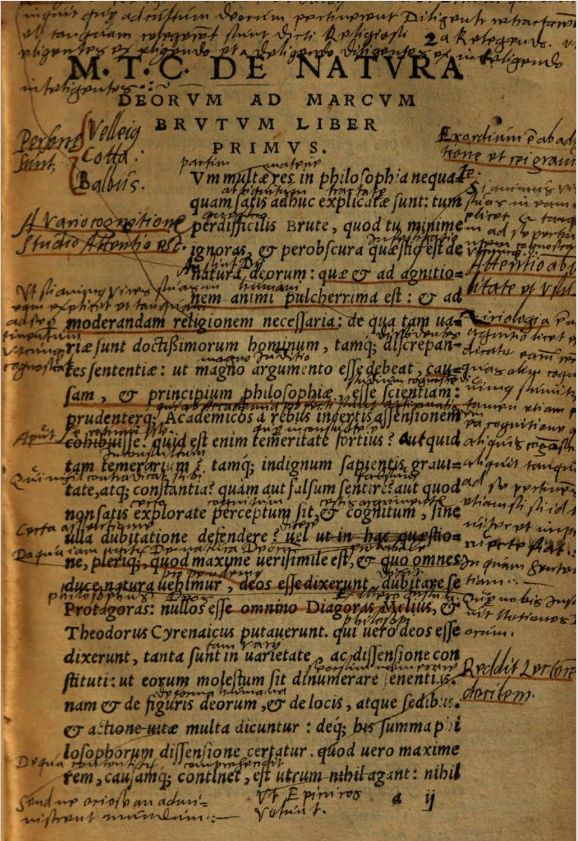

To my surprise, I was not able to order this book through the online catalogue of the BL (although I was later assured by a librarian that this should still be possible), but was referred to its digital version – the book has recently been digitized by Google. Duly I opened the digital version of the second volume, but my initial enthusiasm vanished as a saw how sloppy a job had been done.

A number of marginal annotations which decorate this particular copy have been trimmed, instantaneously rendering this book useless for those of us who want to examine the annotations. Compare this image, for example, with the image above (a picture which I took myself some time ago).

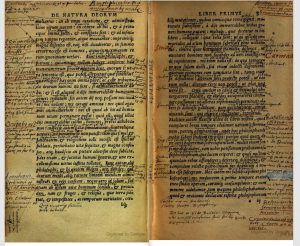

Based on a quick inspection of the digital copy, it seems that the marginal notes in the gutter have been completely captured, whereas the marginal annotations in the outer margins often have been trimmed, as can be gleaned from the following image:

Compare this with the picture of the same opening I took:

In general, the annotations in the gutter are most difficult to capture, in particular when a book is tightly bound. That does not seem to have been the problem here, so it is a mystery why so many annotations have been trimmed. Perhaps this has something to do with the particular process of digitization employed by Google, is simply the result of a lack of interest or knowledge, or is caused by the lasting influence of the idea that only the printed text really matters. It is, after all, not so long ago that collectors and booksellers preferred to have ‘clean’ instead of ‘dirty’ books and resorted to various methods in order to restore their books to their (presumed) original and pristine state (see William H. Sherman, Used books, Ch. 8). Whatever may have caused these flaws, this particular digital version is nothing more than a pale and incomplete representation of the original object. It still is useful, but only to a very limited extent. The process of digitization always involves some loss, but digitization done badly hampers rather than furthers scholarship.